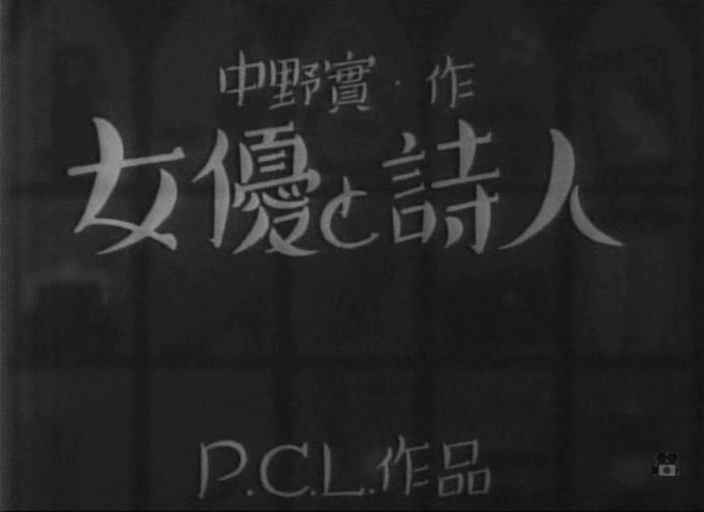

Among the directors most closely associated with the golden age of Japanese cinema, Mikio Naruse is not usually remembered for his sense of humour but his pre-war work often saw him making uncomfortable forays into the shomin-geki comedy. The Actress and the Poet (女優と詩人, Joyu to shijin), Naruse’s second film after leaving Shochiku for P.C.L, is among the more successful but also tinged with characteristic irony that says this is funny because it’s not funny at all.

Among the directors most closely associated with the golden age of Japanese cinema, Mikio Naruse is not usually remembered for his sense of humour but his pre-war work often saw him making uncomfortable forays into the shomin-geki comedy. The Actress and the Poet (女優と詩人, Joyu to shijin), Naruse’s second film after leaving Shochiku for P.C.L, is among the more successful but also tinged with characteristic irony that says this is funny because it’s not funny at all.

The generic shomin-geki setup finds us in a small community of suburban houses where mild-mannered poet Geppu (Hiroshi Uruki) lives with his successful actress wife Chieko (Sachiko Chiba). Amusingly enough, and in a motif which will be repeated, the film opens with an high impact scene of a woman screaming after being threatened with a knife, but thankfully it turns out that Chieko and her friends are simply rehearsing for a play. The actors dispatch Geppu to fetch them some cigarettes, which brings him into contact with his no good “friend” Nose (Kamatari Fujiwara), a struggling writer who is absolutely sure his latest work is going to win a big prize which is why it’s not a big problem that he’s so behind on his rent that he’s been coming and going through the upstairs window so he doesn’t attract the attention of his landlady.

When we first meet Geppu he’s wearing a pinny and cheerfully hanging up the washing. A young man passes by on a bicycle and seems surprised, asking if he himself really did all that laundry to which Geppu somewhat improbably replies that it’s all second nature when you’ve been in the army. Even though this is obviously a very “normal” day for Geppu, the questions keep coming. Ohama (Haruko Toda), the nosy woman from next-door, remarks that everyone in the neighbourhood loves Geppu because he’s just so nice but he’s also become a hot topic with the ladies at the bathhouse because no one’s quite sure what it is he “does”. In the modern parlance, Geppu is a basically househusband who dabbles in “poetry”, or as Ohama later explains “songs for children”.

In this fiercely modern environment, it’s Chieko who wields the financial power while her husband appears not to mind trailing behind. She wears kimono but often with luxurious furs which might lead to us ask why they live in this modest suburban house rather than in the bright lights of the city, but even so the marriage appears to be a happy and progressively equal one. In fact, as we later discover, there’s never been a cross word between Geppu and his wife, which is a problem because Chieko’s latest role involves a marital tiff and she’s struggling to get to grips with it because she doesn’t know what it’s like to fall out with your spouse. To figure it out she gets Geppu to read lines with her in a situation which eventually repeats in their real life when Nose bamboozles Geppu into letting him stay in the upstairs room rent free, leading to an almost identical fight watched calmly by Nose and Ohama who think they’ve got ringside seats to a play they could never afford to see.

Nose’s intervention unbalances the couple’s relationship in that it forces Geppu to reassert his masculinity. “A promise between men is a serious thing”, Geppu affirms “I can’t just go back on it because my wife says no”. Chieko reminds him, however, that this is technically her house – she pays all the bills, while his “writing” career is good only for the odd box of sponge cake. She doesn’t like it, perhaps understandably, that he’s “invited” a ne’er do well to come and live with them without even bothering to talk to her about it. She tries to put her foot down, but Geppu remains as irritatingly passive as ever only slightly putout to have his subjugated status suddenly used against him.

Naruse ends the picture with a comic sequence in which Chieko sees the light. Thanks to her real life argument with her husband, she’s figured out how to perfect her performance but she’s apparently so method that she also begins to embrace her role as a conventional wife off stage too. Rather than Geppu letting her sleep in and cooking the breakfast himself, this time it’s Geppu wrapped up in a futon while Chieko chops veg downstairs. Nevertheless, there is a minor irony in this moment of domestic bliss in that it directly follows the news that the nice young couple who just moved in across the road have committed double suicide because of his embezzlement and subsequent debts. Neatly underlining the consumerist trends of the age, the couple wanted to die in their own home even if it was only “theirs” for a few moments. Meanwhile, Ohama and her insurance salesman husband are busy having a blazing row next-door which just goes to show that old-fashioned marriages aren’t so happy either.

Chieko superficially plays the conventional wife, engaging in a little role-play with her husband while Nose listens on from the stairwell, but theirs remains a very modern marriage in which she is free to fulfil herself outside the home and her husband is seemingly unbothered (to a point at least) by the mild censure of the local ladies who both love him for his niceness and perhaps dislike him for it too. Naruse undercuts the conventionally “happy” ending in which traditional gender roles are restored and the family rebalanced by ending on a note of irony as the home of Ohama, a traditional wife dominating her henpecked husband in a comic yet socially accepted fashion, is thrown into violent discord while all is peaceful in the decidedly modern house of Geppu.