“Psychologically, I’m a man who is already buried in the ground,” laments one of the “converted”, “I just wish I could get out of here”. Kim Dong-won’s landmark 2004 documentary Repatriation followed a series of “unconverted” long-term prisoners who had been sent to the South as spies and were later caught but refused to abandon their ideology. A historical turning point in the relations between North and South allowed these men who longed to return home to do so, but others were refused on the grounds that superficially or otherwise they had “converted” and renounced North Korean Communism to live more freely in the South.

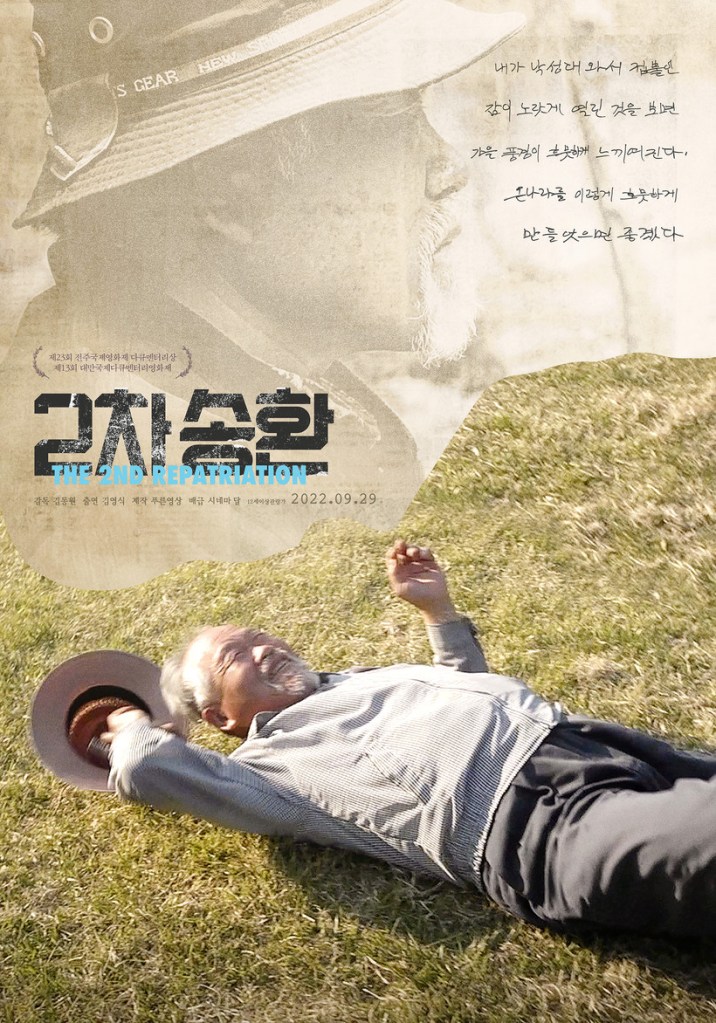

Almost 20 years in the making, Kim’s followup documentary 2nd Repatriation (2차 송환, 2 Cha Songhwan) follows those who were left behind but have never abandoned their ideology in their hearts and are determined to return to the North. Just as in the earlier film, Kim frames them as essentially caught in a kind of no mans land between two nations and two ideologies, used and misused as tools of each but also pawns at the hands of geopolitical manouvering. Though Kim had assumed a second repatriation would follow soon after the first, this was not to be because of changing political realities not only in Korea but in the US whose influence many regarded as essential in brokering peace across the peninsula.

Kim’s main protagonist Youngshik is a cheerful and vibrant man, but sometimes descends into aggressive rants about “bastard Americans”. As the documentary is quick to point out, there is truth in some of what he’s saying regarding the undue influence of and risks of military dependency on American forces, but the strength of his language often lays bare the rigidity of his ideology. Later in the film, a younger man asks Youngshik if there aren’t things that worry him about the state of North Korea today in the reports of widespread famine, but Youngshik appears to not really listen to him before brushing it off as all the fault of the Americans. Anything that’s wrong with North Korea is the Americans’ fault, but then so is the division itself so callously drawn up as an overture in a proxy war. Nevertheless, in the 2020 US elections he finds himself rooting for Trump based solely on the single issue of North Korean relations believing his election may pave the way for an eventual reunification despite the vast ideological gulf that must necessarily exist between them.

Youngshik has indeed never given up his mission and is seen giving speeches on the subway and protesting outside the Ministry of Unification crying out for peace. He claims that he “converted” only superficially after being tortured but feels ashamed of his actions. A second issue arises when a group representing the families of those kidnapped by North Korea objects to the repatriation on the grounds that their relatives will not be afforded the same opportunity asking for something more like a prisoner swap. But Youngshik and the North Korean authorities deny that any kidnapping took place, insisting that anyone captured by the regime after accidentally straying into its territory would have been allowed leave if they so wished laden down with rice, fish, and fresh clothes. Another of the converted speculates that they may have chosen to stay because the South Korean state would simply have confiscated everything they’d been given. Some fisherman who did return were punished under the Anti-Communism laws or accused of spying.

Each side is keen to use those caught between them for their ends with the truth an unintended casualty. Meanwhile the irony remains that both the kidnapped and the former North Korean spies have been forcibly separated from their families by political forces beyond their control. Youngshik insists that he came to erase a border but has since been trapped by it, unable to understand the absurdity which prevents him from visiting his home. On one particular occasion, he is permitted to visit North Korea but only to a single village set aside for that purpose pointing at his hometown which he says lies just over the hill. In any case Youngshik is by that point in his 80s. After he learns that his wife has passed away. He begins to despair wondering what the point of returning home would be. His children would be strangers to him. They may harbour resentment or perhaps they would not get along.

Despite his convictions life in the North must be very different and romanticisation of it as an exile a dangerous fantasy. Youngshik tells the man who asked him about famine that life the North was easier in part because there was no need to think. Your basic needs are taken care of so long as you do the work assigned to you whereas in the South you have to take care of yourself, no one will help you, and if you cannot work you cannot eat. The life of Youngshik and those like him is necessarily hard, ill equipped to survive in a capitalist society and without support network outside of each other save a few volunteer groups. One of the other men who married a South Korean woman explains that he is still working long hours at a physically strenuous job despite a heart condition because he has no other choice. Another who also married prepares to divorce his wife and return to the North ensuring she will inherit their home and face no financial penalty but otherwise resolved to abandon her in the hope of reuniting with the family he once abandoned if not entirely through choice.

Only one of the men, who resented by the others, states that he did not come by his own volition and on balance prefers to stay in the relative freedom of the contemporary South. Each of the others is desperate to return and trapped in a kind of limbo unable either to make a life in the South or cross the border into a life which may still be rootless and uncertain. Some say the previous returnees were forced to marry in part to have someone to take care of them in their old age, assuming their families would not or could not do so, and in order to monitor them to ensure they had not been turned or were engaged in a counter mission against the North. In the end Kim is not able to complete his story with the prospect of a second repatriation ever more distant. Even his own trip to North Korea in search of his secret history is rendered impossible. The liaison company ironically suggest he send a foreigner instead, a Korean-Norwegian producer appealing through another Asian nation apparently having more luck. A list of the names of applicants for the second repatriation at the film’s conclusion lists many as deceased while those surviving are already over 90 and left with nothing else than the desire to return to a homeland that seems as if it may have forgotten them.