The irony at the centre of the Folger family is that they cannot communicate effectively because they’re each afraid of blowing their cover. Adapted from the manga by Tatsuya Endo, Spy x Family was the smash hit anime of 2022 and now makes its way to the big screen with an epic adventure which threatens the foundations of a “fake” family which has become increasingly real to the extent that it may have come to eclipse the reason it was created.

Newcomers to the franchise need not fear as the film is broadly standalone and gives a brief explanation of its setup in not dissimilar fashion to the voiceover intro of the TV anime. Codenamed “Twilight”, spy Loid Folger (Takuya Eguchi) has adopted a little girl, Anya (Atsumi Tanezaki), and married a local woman, Yor (Saori Hayami), in order to infiltrate an elite boarding school with the aim of targeting a reclusive politician through forging a connection with his younger son, Damian. What Loid doesn’t realise is that he’s completely in the dark about his new family. Anya is the only one who knows the whole truth as she is a telepath, while Yor is a secret assassin who agreed to fake marriage as cover to avoid detection by the authorities. Even the family dog, Bond, is a canine clairvoyant who was the product of an experimental program to breed super intelligent dogs.

The mission is compromised by the fact that Anya is less than academically gifted and unlikely to gain all eight stars needed to join the elite group of students that would get her close to Damian and Loid close to his father. Having made so little progress, Loid’s handler reveals Operation Strix may be taken away from him and given to a political crony which would necessarily mean he’d have to give up the new family life to which he’s gradually become accustomed. But the family is also threatened by Yor’s insecurity and conflicted feelings for Loid, well aware their arrangement is “fake” but still anxious that Loid is having an affair and worried he’ll divorce her for not being good enough at the domestic life she too has come to value. Anya, meanwhile, obviously wants to keep to her new family together while helping her parents with various missions but can’t say anything for fear of exposing herself as a telepath and Bond as a clairvoyant.

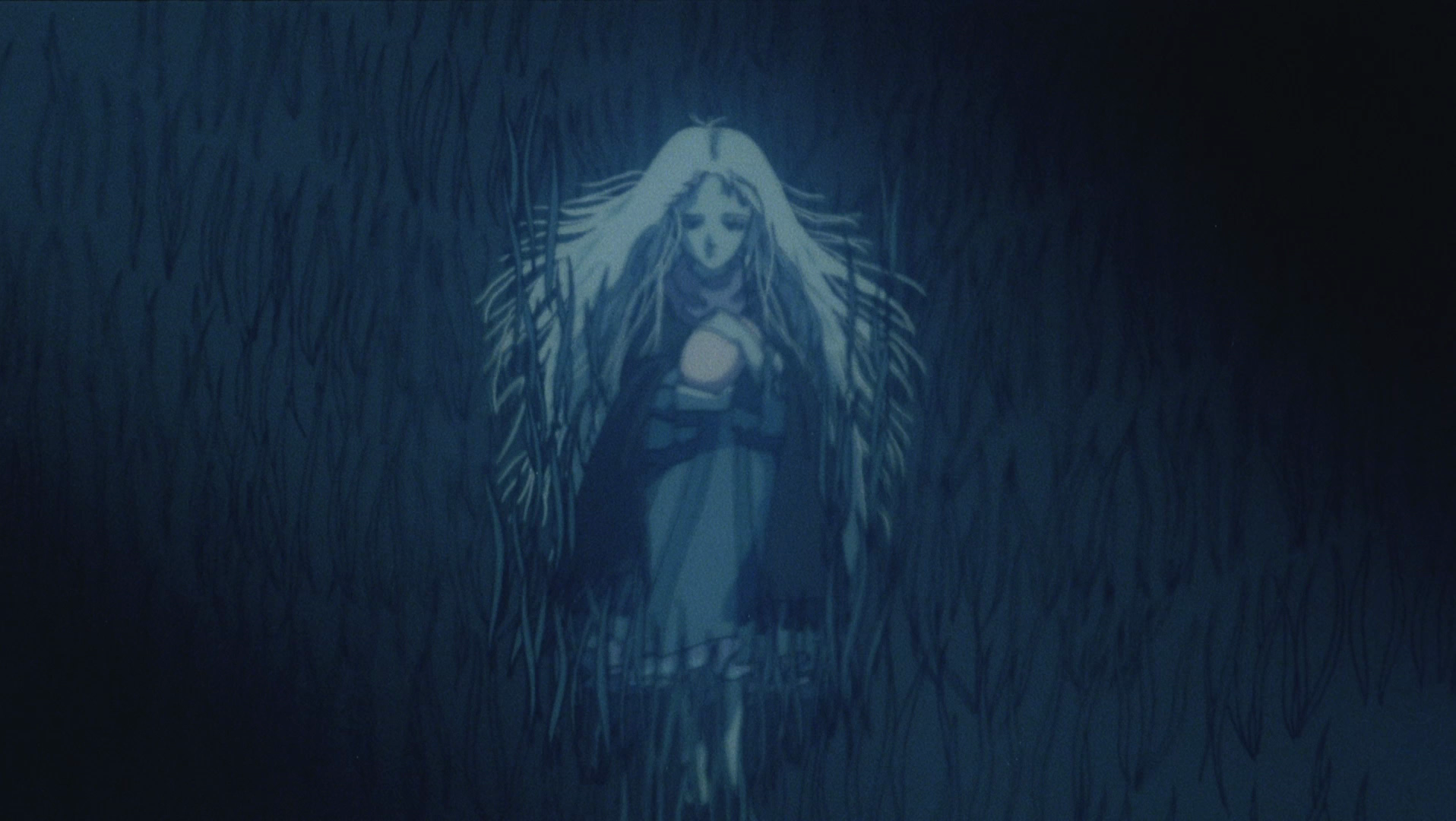

Echoing the extended cruise arc from the anime, the film follows the Forgers on a mini break to nearby Frigis in search of a regional dessert they hope will help Anya win another star only to end up swept into local politics. The long-form format of the feature surpasses that of the TV series in shedding its bitty, episodic structure for something more substantial though that may of course detract from its charms for those taken by the isolated vignettes of the show. Even so, the film doesn’t stint on quickly humour gaining the ability to deepen its ongoing gags culminating in a fantasy sequence animated like a kids drawing in which Anya meets the God of Poop and is rewarded for excellent service.

Though what’s really about is once again the Forger family who must finally turn the wheel together in order to avoid certain death. Though fighting parallel battles, unable to simply explain what they’re doing and ask for help, the gang eventually end up in the same place united in their missions and also as a family having faced off various threats and reaffirmed their bonds which have by this point become very much real. Loid continues to struggle with the mechanics of his mission, frequently unable to read Yor’s insecurity and unwittingly fuelling it, and exclaiming that he doesn’t understand children nor have much clue how to manage Anya’s often madcap behaviour. The irony is that if he succeeds, the family will have to disband and he’ll lose this new sense of domesticity that’s becoming used to, but if he fails his nation may go to war and thousands of people will die. But until then his biggest problem is figuring out how Anya can win a baking contest and survive yet another impromptu family holiday without becoming embroiled in an international conspiracy.

SPY x FAMILY CODE: White is in UK cinemas now courtesy of All the Anime.

UK trailer (English subtitles)

Images: © 2023 SPY x FAMILY The Movie Project © Tatsuya Endo/Shueisha