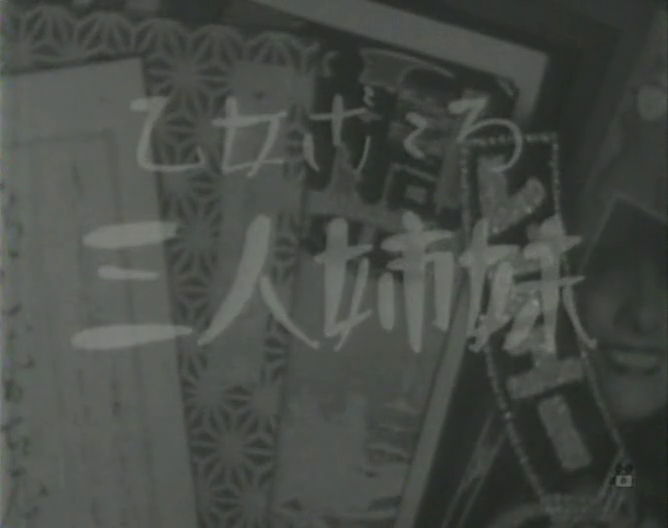

“From the youngest age, I have thought that the world we live in betrays us” Mikio Naruse is often quoted as saying, and it’s certainly an idea which informs much of his filmmaking. 1935’s Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts (乙女ごころ三人姉妹, Otome-gokoro Sannin-shimai), adapted from a short story by Yasunari Kawabata, is indeed a tale of the world’s cruelty as its saintly heroine attempts to escape her austere mother’s icy grip through kindness alone but finds her efforts frustrated by the world in which she lives.

“From the youngest age, I have thought that the world we live in betrays us” Mikio Naruse is often quoted as saying, and it’s certainly an idea which informs much of his filmmaking. 1935’s Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts (乙女ごころ三人姉妹, Otome-gokoro Sannin-shimai), adapted from a short story by Yasunari Kawabata, is indeed a tale of the world’s cruelty as its saintly heroine attempts to escape her austere mother’s icy grip through kindness alone but finds her efforts frustrated by the world in which she lives.

Osome (Masako Tsutsumi) is the middle of three sisters raised by a cold woman (Chitose Hayashi) who forced her daughters to earn their keep by playing the shamisen on the streets of Asakusa. Oldest daughter Oren (Chikako Hosokawa) left the family some time ago after falling in love with a salaryman and hasn’t been heard from since, and while Osome is still expected to ply her trade, youngest daughter Chieko (Ryuko Umezono) has been spared, becoming a “modern girl” currently working as a dancer in a revue. Unbeknownst to her family, Chieko has also got a boyfriend – the handsome and seemingly quite wealthy Aoyama (Heihachiro Okawa) who runs into Osome by chance in the street and offers her a handkerchief to help fix her broken geta. This is not the story of a love triangle, however, so much as cruel fate accidentally bringing the sisters back together through a shared destiny.

While Chieko idly muses that it might have been better if her mother had opted for group suicide (joking with her lover about dying together as was apparently a fad at the time), Osome tearfully asks her to “please accept us as we are” but her pleas largely fall on deaf ears. Having taken in a series of apprentices, Osome’s mother continues to treat them cruelly, berating them for not picking up the shamisen, and insisting on “discipline” when she discovers one of the girls has had the temerity to buy a magazine with some of the money she herself has earned. Osome, in a characteristic act of kindness, insists she bought the magazine as a morale booster only to receive her mother’s scorn. “I put so much effort into raising you, but you still haven’t become people who’ll give an honest day’s work” she complains, commodifying them once again. “You don’t know how much easier it would be to go out and earn money myself”, she adds unconvincingly, telling her daughter she can always leave if she doesn’t like it despite having irritatedly complained about Chieko’s increasingly late return home and the possibility she may leave just like Oren did.

As Osome tells us, she and her sister were forced to play the shamisen in unsavoury Asakusa from only eight years old. As they got older, Osome was worried about the attention Oren seemed to be getting from “rough” men in the streets. Eventually Oren stopped carrying her shamisen at all and fell in with a bad crowd, only escaping when she met her husband Kosugi (Osamu Takizawa). Kosugi, however, is ill with TB and finding it difficult to hold down a job. Increasingly jealous and paranoid, he is afraid Oren will hook up with her old gangster friends and fall back into bad habits. Meanwhile, Osome is still playing her shamisen and putting up with rough treatment from the drunken clientele who sometimes try to manhandle her or make unreasonable requests. An irritated bar owner eventually knocks on a record to drown her out as if signalling her impending obsolesce.

Nevertheless, the older two sisters have largely remained traditional. Oren’s fall into the gangster underworld is signalled by a sighting of her in Western clothes, looking like a well to do young lady as Osome puts it, but once with Kosugi she soon reverts to kimono and fully embraces the role of a conventional housewife supporting her husband with all her strength. Chieko, however, is a “modern girl”, dancing in a nightclub revue and dressing exclusively in Western fashions. Some horrible boys who make a point of singing the rather vulgar song back at the girls through the window yell “modern girl” at her in the street, indicating just how shocking and unconventional her appearance was back in 1935 even in the backstreets of Asakusa. Nevertheless, Chieko appears to have found a satisfying romance with a “modern boy” in Aoyama who dresses in suits and seems to have a bit of money but is undeterred by a possible class difference and just as nice as his potential sister-in-law.

Despite Osome’s attempts to reunite the sisters, fate conspires against her. Oren hooks back up with her lowlife friends who use her in a plot to extort Aoyama while she remains completely unaware that she’s targeting her sister’s young man. Osome tries to tries to stop them but is stabbed by thugs in the process and, figuring out what’s happened, keeps Aoyama and Chieko away from the station where she has arranged to bid Oren goodbye on the last train out of Ueno. Poignantly, Oren seems happy that her sister has found someone nice, saying that she’d have liked to meet him still unaware she already has. The sisters know they likely won’t meet again, and Osome is content only in knowing that in theory at least she has saved the memory of the bond they once shared through preventing Oren’s involvement in the incident with Aoyama from coming to light.

Osome’s kindness is her undoing. Her world betrays her, she is simply too good, too pure-hearted to be able to survive in it. The three sisters struggle to overcome neglectful parenting, but their mother has at least survived if unhappily, suggesting the world is kinder to those whose hearts are colder. Oren and Chieko go their separate ways, into the past (on a train) and the future (by car), but Osome remains stubbornly in the waiting room with only the inevitable awaiting her.