Clearly influenced by the classic Japanese ghost cat movie and the work of Nobuo Nakagawa, Lee Yong-min’s nightmarish slice of gothic horror The Bloodthirsty Killer (殺人魔 / 살인마, Salinma) winds a tale of female revenge though somewhat incongrusouly positioning the vengeful spirit’s oblivious husband as the hero who must attempt to save his family by exposing the corruption at its centre. That corruption is intensely and exclusively female but informed mainly by entrenched patriarchy along with growing anxieties amid increasing wealth disparity.

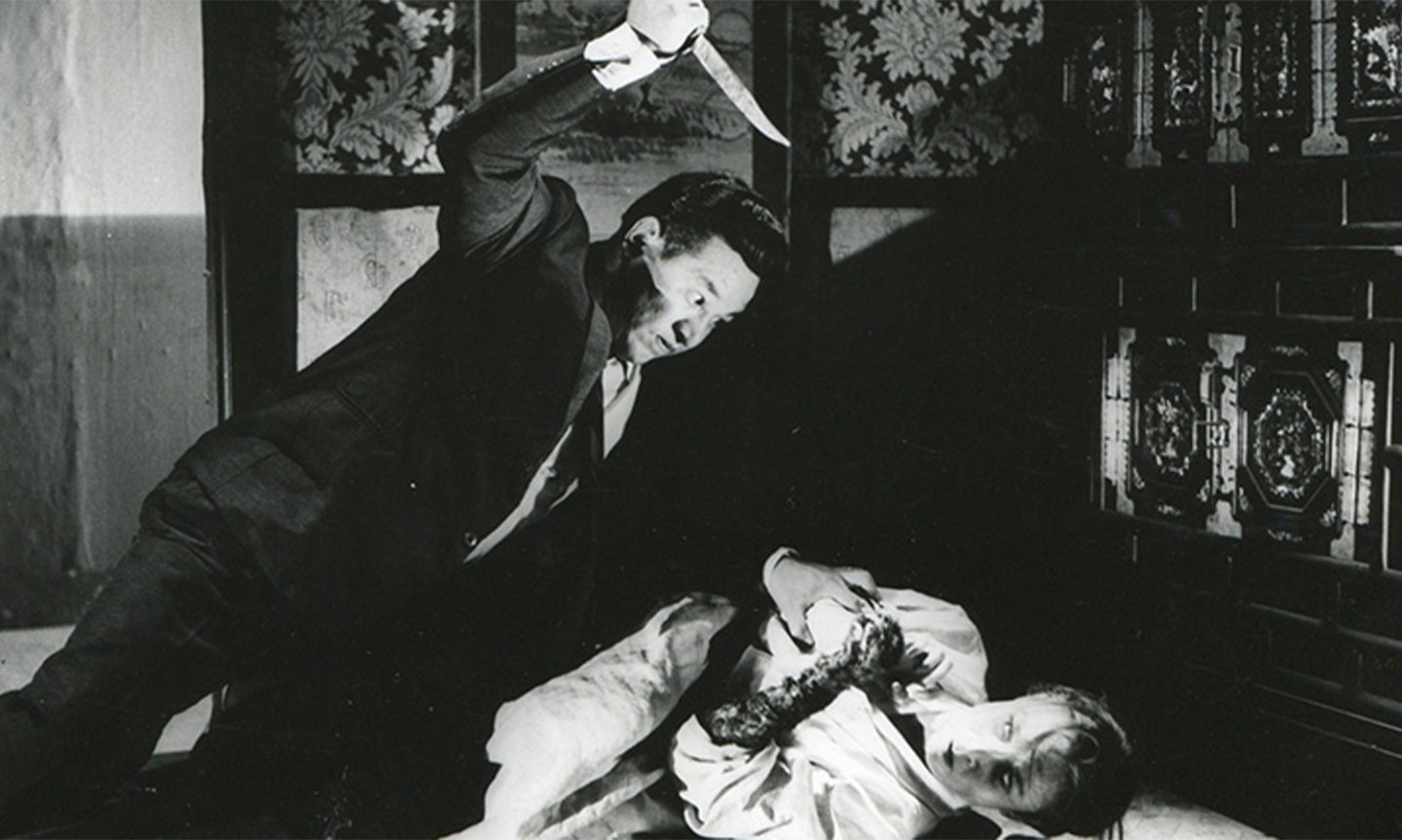

As in Nakagawa’s The Lady Vampire, a woman makes a surprise reappearance 10 years after being declared dead looking exactly as she had the last time her husband saw her while also featuring in a painting though this time not in the nude but melting as soon as the confused hero, Simok (Lee Ye-chun), picks it up for a closer look. Lee opens with an incredibly gothic, dreamlike sequence in which a creepy man watches Simok walking in the rain before taking him to a gallery that turns out to be entirely empty. A security guard informs him that the exhibition is over, the painting of Aeja (Do Kum-bong) the only one remaining. It also transpires that Simok has made his trip on the one day a year ghosts roam the earth, as the creepy taxi driver points out gesturing towards a field which appears to be full of white-clothed figures. Eventually he arrives at an eerie house in the woods where he meets the main who painted the portrait only to see him murdered by Aejan while the painter survives long enough to hand him the painting and explain that it contains “a secret”.

This secret will relate closely to Simok’s family which on his return home we can see is affluent and apparently happy. Simok lives in a large, Western-style house that is perfectly primed for gothic horror. When he tries to explain to his wife, Hyesuk (Lee Bin-hwa), what he thinks has happened, a cabinet door mysteriously opens on its own before the couple begin hearing the screams of Simok’s mother who claims a ghost tried to strangle her in her room. All things considered, it does not actually take them very long to agree that ghosts are real and they’re being targeted by one though the reason remains obscure to all, or perhaps to all but Hyesuk whose demeanour immediately changes. Despite having gone into a frenzy when her eldest daughter Mihwa was snatched by the ghost, she quickly makes her way to her hidden stash exclaiming that she’s still “young and rich” and plans to enjoy the rest of her life. The ghost can take her kids, but it won’t get her.

This is of course entirely contrary to contemporary codes of motherhood especially as we realise that one of the causes of Aeja’s downfall was her childlessness. Three years into her marriage with Simok, she had born no children and earned the animosity of her mother-in-law (Jeong Ae-ran) who it seems did not really like her and felt that she did not live up to her traditional ideas of idealised femininity. Perhaps partly for aesthetic reasons seeing as she is a ghost, Aeja dresses exlcuvely in hanbok in contrast to Hyesuk who in flashbacks is seen in only Western clothing and declares herself jealous and resentful not only of the couple’s material comfort but of how happy they seem to be. A kind of poor relation, Hyesuk plots revenge on societal unfairness in wilfully disrupting Simok’s household by manipulating patriarchal social codes in causing Simok to believe Aeja has been having an affair during his lengthy business trips to Japan.

By the same token, she also takes advantage of the grandmother’s affair with a married doctor (Namkoong Won) which is taboo on several levels the first simply being the existence of sexual desire in a middle-aged woman. Later, once she has been possessed by the ghost cat, Simok’s mother will similarly manipulate him in claiming that she has spent all her life in his service clinging to the memory of her dead husband who left her widowed at 30 as an advocation of idealised womanhood. Though Simok has realised that she was no longer his mother but a ghost cat on catching sight of her reflection, he was unable to kill her because of all her reminders about her maternal suffering. It’s the desire to maintain this facade that encourages her to reject Aeja after Hyesuk engineers her walking in on her mother-in-law and the doctor, insisting that Hyesuk, who is pandering to her, would make a much better daughter-in-law than the righteous and wronged Aeja.

Aeja’s revenge is also against all of these oppressive social codes that have contributed to her demise though it was other women who eventually brought it about in their enforcement and manipulation of the codes of femininity. Recalling a moment from Hajime Sato’s Ghost of the Hunchback in a which a shamaness drops in having spotted all the evil emanating from the house, another woman later turns up and seems to want to help giving Simok a magic talisman he eventually uses to save his kids who have been imprisoned, perhaps for their own safety, inside some Buddhist statues. In contrast to Aeja’s rage, Hyesuk’s greed, and the mother-in-law’s shame, the mysterious woman is gentle and self-assured if a little eerie. Just as a cross can stop a vampire, so a Buddhist rosary can fend off a ghost cat while it’s an appeal to Buddha that eventually helps to break the curse transforming the portrait into a lotus instead.

In any case, Lee adds a playful irony to the genre as the grandmother in particular begins to take on feline mannerisms, hissing and pawing at the Buddhist statues while licking her granddaughter’s face in a way even her grandson Woong realises is “disgusting” and not something his grandmother was usually accustomed to doing. In a nod to Yotsuya Kaidan, Aeja’s metamorphosis into a vengeful ghost is accompanied by a loss of her hair, symbolising her loss of femininity, along with a large disfigurement over her eye that has become closely associated with that of Oiwa. Then again, he also has fun with a transformation scene as the grandmother is defeated and turns back into a cat complete with a tiny dress that shrinks with her. What he otherwise conjures is however an eerie sense of dread hanging over a superficially happy home with a terrifying secret at its centre, though what it does in the end suggest with its ambiguous messaging is that the father will eventually have to take responsibility for his family and play an active role in the domestic space if he is to escape this very particular curse of familial corruption.