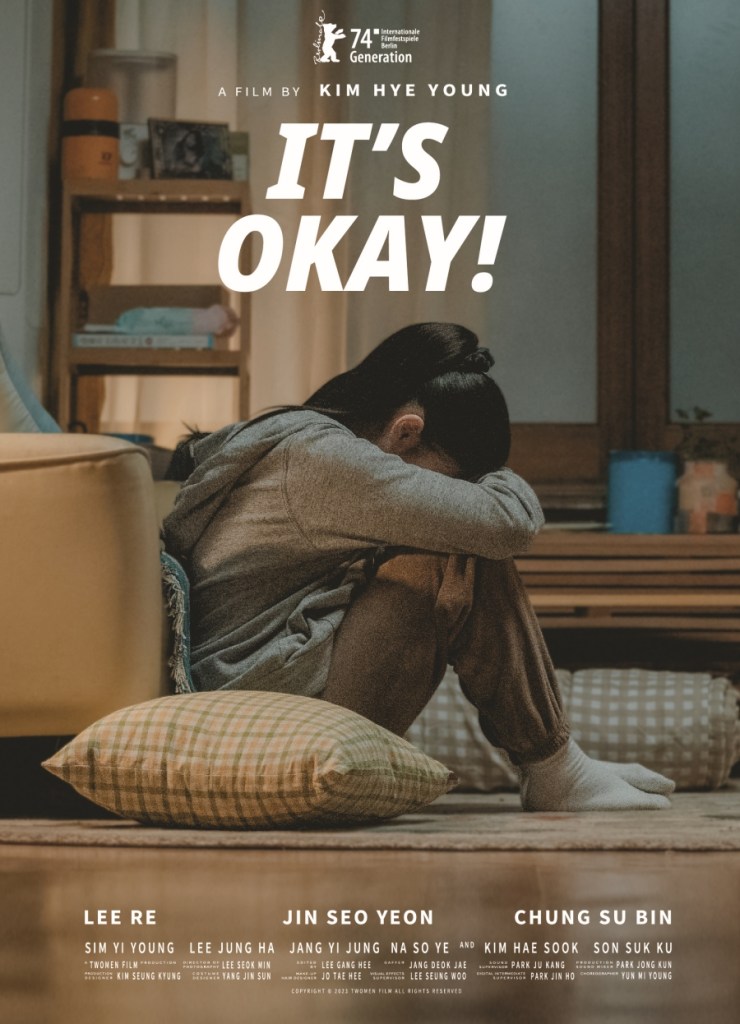

The ironic thing about the title of Kim Hye-young’s debut feature It’s Okay (괜찮아 괜찮아 괜찮아!, Gwaenchanh-a Gwaenchanh-a Gwaenchanh-a!) is that for the most part it really isn’t but the ever cheerful heroine In-young (Lee Re) manages to face her hardship and loneliness with down-to earth-practicality and good grace. It’s her infectious happiness that begins to improve the lives of those around her, many of whom have their own issues often stemming from entrenched patriarchy, classism, and a conformist culture that railroads the young into futures they may not want and will not make them happy.

At least that’s how it is for Na-ri (Chung Su-bin), the star of Il-young’s traditional dance troupe who has developed bulimia partly to adhere to contemporary codes of feminine perfection but also as a means of asserting control over her life which is otherwise micromanaged by her mother, once a dancer herself but now a wealthy housewife who uses her privilege to ensure her daughter is always centrestage. For these reasons she crassly remarks that she envies Il-young whose mother was killed in a car accident leaving her orphaned and entirely alone but in Na-ri’s eyes free and independent.

It’s Na-ri’s mother who later refers to Il-young as a “worthless” person who does not deserve and will not have the opportunity to steal Na-ri’s spotlight even if she were good enough to seize it. The other girls in the troupe resent Il-young because her fees are paid by a scheme set up to help children of single-parent families, though technically she isn’t one anymore. They think it’s unfair she doesn’t have to pay when they do and also look down on her for being poor and an orphan when the rest of them come from wealthy backgrounds and are serious enough about traditional dance to consider going on to study it at university. Il-young isn’t a particularly good dancer nor does she put a lot of effort into it, but unlike Na-ri whose dancing is technically proficient but cold Il-young dances with a palpable sense of joy.

That might be why she catches the attention of otherwise stern choreographer Seol-ah (Jin Seo-yeon) who harbours resentment towards Na-ri’s snooty mother but lives a life that seems very repressed, tightly controlled and devoid of the kind of exuberance that comes naturally to Il-young. Her palatial apartment is cold, neutrally decorated, and spotlessly clean while, contrary to Na-ri, she forgoes the pleasures of eating subsisting entirely on green health drinks. Her decision to take in Il-young after finding her secretly living at the studio after her landlord evicted her from the home her mother had rented, may also reflect her own desire for a less constrained life and the familial warmth which seems otherwise lacking in her overly ordered existence. Gradually nibbling at the fried spam Il-young has a habit of cooking in the morning, she begins to open herself to the idea of a less regimented, happier life.

The same is true for Na-ri who is fed up with being forced to live out her mother’s vicarious dreams, literally letting her hair down and abandoning her need for control and dominance to embrace more genuine friendships with the other girls including Il-young. The lesson seems to be that there’s too much pressure placed on these young women in a society that dictates to them who and what they should be while shunning those like Il-young who are defiantly who they are and all the more cheerful for it even in the face of their hidden loneliness. Yet as Seol-ah eventually tells her, you’re the centre of wherever you are and Il-young’s life is her own to live in the way she chooses.

What emerges is a sense of female solidarity in the various ways Il-young is also parenting Seol-ah as she at first perhaps grudgingly offers her support and acceptance while taking on a maternal role that allows her to break free of the rigidity which had left her so unhappy. Told with a true sense of warmth that belies an inner melancholia, the film advocates for laughing through the tears and meeting with the world with an openhearted goodness that in itself allows others to break free of their own grief and pain and discover a happiness of their own bolstered by a sense of friendship and community rather than live their lives isolated and alone to conform to someone else’s ideal.

It’s Okay! screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)