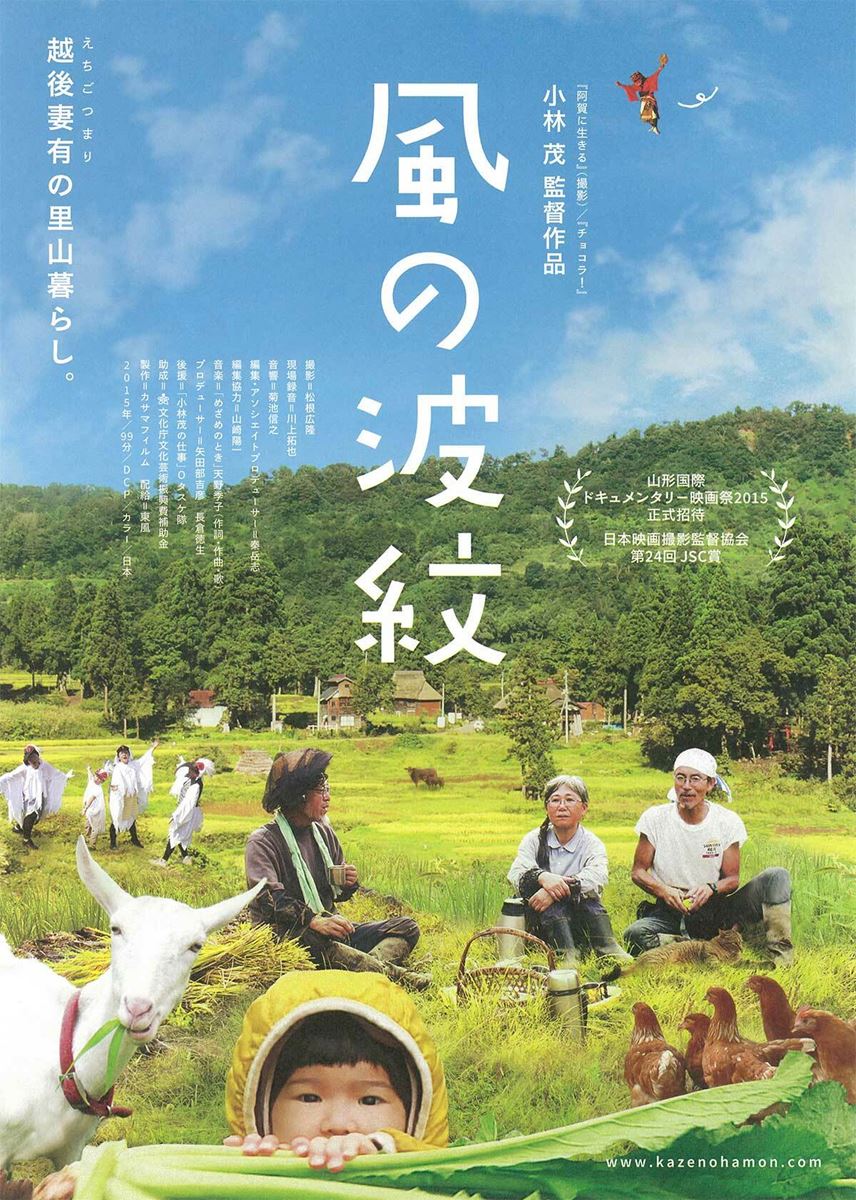

“You can’t live here alone” a older woman admits having long left the village and returning only to visit her parents’ graves to be shocked by its ongoing decline. Shigeru Kobayashi’s mostly observational documentary loosely follows the life of a middle-aged man who left Tokyo for a life in the mountains only to be frustrated by the March 2011 earthquake. Undeterred, he ignores the advice of a local builder that his 117-year-old home is damaged beyond repair and forges on together with the support of the surrounding villagers to rebuild and restore.

It could in a way be a metaphor for the nation’s determination to do the same in the way of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, but it’s also for Kogure a personal mission to fulfil his dreams of country living. Indeed, he gleefully tends to his rice paddies which he says he’s kept chemical free rather than allow them to be polluted by the modern society. Then again, perhaps this is easy for Kogure to say given that he describes his farming to a fellow farmer as a “hobby” and it’s otherwise clear that he’s not using it as a means to support himself. For these reasons he takes pleasure in the simple though arduous acts of planting and harvesting, pushing a wooden plow through the field and revealing that he discovered the traces of those before him in the remnants of an old irrigation tunnel now buried by mud. For him, this sense of continuity seems to be central as if he’s preserving something of an older Japan and a simpler, more fulfilling way of life.

Kogure had said he wanted to save the house because it was like the pillars cried out to him. A local dye artist says something similar in that he almost feels the wood he harvests is alive though if it were he wouldn’t be able to cut it. There is a sense of the forest as an almost sentient entity with which the villagers live in harmony, but also a less wholesome vision of nature red in tooth and claw as Kogure offers up one of his goats to have its buds removed with hot iron by a local goat expert. The poor thing cries in pain but is ignored, the expert simply stating that it’s only natural and what is always done though it seems if it really is necessary there must be a less cruel way to do it. Kobayashi later wisely cuts away as we realise a goat is about to be slaughtered, cutting straight to the “meat carnival” it provides for the villagers.

Most of those interviewed are themselves transplants like Kogure who moved to the mountains 20 or 25 years previously usually from the cities and have largely adapted to a simpler way of life, though it’s also true that there are few young people besides a young woman and her daughter who cheerfully exclaims that rice is her favourite food. The woman is grateful for the unconditional support and acceptance she’s received from the villagers whom she says smile in the face of hardship, keen to help each other and make sure that no one is excluded. Yet this way of life is often hard and it’s true enough that no one can survive here alone amid the heavy winter snows. One old man decides that it isn’t worth trying to repair his home after the earthquake and it’s better to demolish it instead while his wife reflects on her life explaining that she was more or less forced to marry him by her family who lured her back from Tokyo on a ruse that her mother was seriously ill.

Nevertheless, Kobayashi demonstrates the closeness of the remaining villagers as they bond together through shared feasts, laserdisc karaoke, and a general sense of community. “Breaks are a big part of shovelling snow” one man jokes, focussing not so much on the unending labour as the pleasure taken in rest and friendship. Another later suggests the snow will become “a memory of a trial I survived” echoing the harshness of this village life in winter, even as the camera cuts to a glorious spring filled with bright sunshine and verdant green. Kogure continues to plant his rice while a goat runs about in the field behind him in a timeless vision of pastoral life despite itself persisting.

Trailer (no subtitles)