A family broken by economic shock and destructive male pride is eventually mended through Christian faith in Torajiro Saito’s 1929 silent melodrama The Dawning Sky (明け行く空, Akeyuku Sora). Though most of his work is currently presumed lost, Saito became known as the “god of comedy” while working at Shochiku’s Kamata studios yet Dawning Sky while affecting a cheerful tone is marked by a sense of sadness and anxiety that perhaps reflects the precarities of the world of 1929.

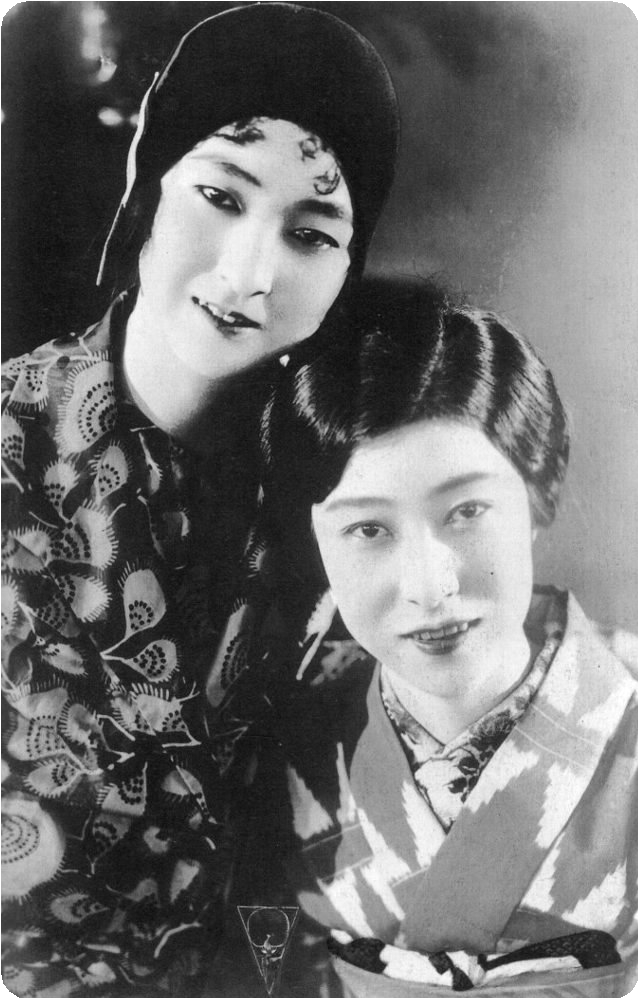

Recently widowed Kyoko (Yoshiko Kawada) has learned to bear her grief by doting on her newborn daughter Reiko, though her world is about to implode as the bank operated by her previously wealthy father-in-law Junzo (Reikichi Kawamura) has collapsed leaving the family in financial ruin. Kyoko’s parents approach Junzo offering to take her back, but the idea provokes only intense resentment in Junzo’s wounded pride as he takes it that they no longer feel his family is good enough for their daughter now that he is no longer rich. A traditionally minded woman Kyoko pleads with him to stay but he will have none of it, throwing her out but insisting on keeping Reiko with him. Out of old-fashioned ideas of loyalty, Kyoko decides that she will not return to her parents nor marry again but is at a loss for what to do sadly wandering about ominously near a bridge before catching sight of the cross on a Christian church and feeling herself saved. Some years later, Kyoko is sent to a small town as a female pastor where, by total coincidence, Junzo is also living with Reiko (Mitsuko Takao) and now working as a lowly coachman.

The cause of Kyoko’s forced dislocation is located directly in the economic shock of the late 1920s which causes Junzo to lose his family bank and with it the social status which gives his life meaning, but it’s also implicitly the demands growing consumerist capitalism which have already undermined traditional familial bonds and responsibilities. Junzo is so consumed by resentment towards Kyoko’s family, who may have made the offer for pure-hearted reasons rather than snobbish disdain for Junzo’s ruined state, that he coldly separates a mother from her child and thinks nothing of the consequences seeing only red in his internalised shame in having failed in business. Yet true happiness is evidently not possible until he finally learns to abandon his lust for material success. “I’m poor, I know, but life is nice and carefree because I have my granddaughter” he explains to one of his passengers having reconsidered his priorities and come to realise it’s familial bonds which are most important after all.

Nevertheless, he continues to hide the truth from Reiko having told her that both her parents are dead while she continues to pine for a mother she’s never known. Her little friend Koichi meanwhile is the only son of his widowed mother who is bedridden and unable to work. As the family is poor Koichi is responsible not only for her care, they’ve rigged up a kind of machine which automatically dispenses her medicine while he isn’t there to administer it, but for the cooking and cleaning too. The two children first bond when Reiko discovers a wounded pigeon shot by Koichi and scolds him that he has no right to kill living things though he only wanted to feed his sick mother, the pair of them deciding to bury the pigeon and give it a proper funeral. This brings her to the attention of the pastor, Kyoko, who is proving especially popular in the local community because of her innate kindness and compassion. But in suspecting that Reiko may be her daughter, Kyoko is at a loss as to how to move forward unwilling to disrupt her life with Junzo by telling her the truth while torn apart inside by her wounded maternity and new duties to her Christian faith.

The film’s overt religious overtones are perhaps surprising for the world of 1929 as is the near universal approval with which the church is viewed in the local community with only the strange and bookish Hide refusing to attend on the grounds that he hates Christians while all of the other children begin hanging out inside largely because of Kyoko’s warmth and kindness. It is finally Christian virtues which allow the family to be repaired, Junzo overcoming his sense of wounded male pride when faced with Reiko’s constant pining as the pair eventually make a mad dash towards the station on learning that Kyoko has decided to leave town rather than risk causing Reiko further pain by disrupting her new life. “God’s grace brought them together” as the benshi intones, yet as much as Kyoko’s maternity is restored she remains a liminal figure returning not to Junzo’s house but only to the church as its pastor recommitting herself to her religious duties while looking out sadly as Reiko plays with the other children in the beautiful countryside suggesting that the ruptured bonds of the traditional family cannot ever be fully repaired.

Saito’s elegant mise-en-scène has its moments of poignancy in the expressionist angles of Kyoko’s walk into darkness or frequent employment of superimposition, not to mention the intensity of its climactic storm scene intercut the with the spiritual ferocity of Kyoko’s desperate praying surrounded by candles in the dark and empty church, but the film is first and foremost a melancholy tale of familial reunion which, while in some senses incomplete, nevertheless suggests that true happiness exists only in simplicity, the family repairing itself through jettisoning contemporary ideas of capitalistic success and social hierarchy in order to embrace their natural affection for each other.