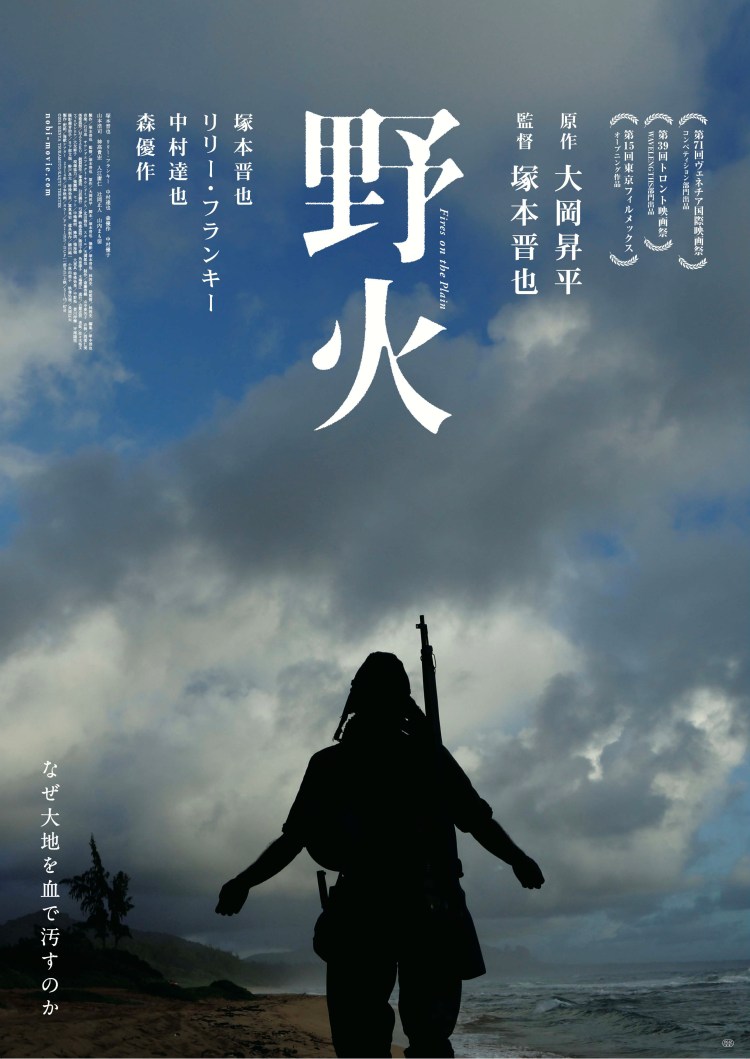

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by Kon Ichikawa in 1959), Fires on the Plain is a disturbing, surreal examination of the effects of war both on and off the battlefield.

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by Kon Ichikawa in 1959), Fires on the Plain is a disturbing, surreal examination of the effects of war both on and off the battlefield.

Late in the war when it’s almost lost though no one wants to admit it, Corporal Tamura (Shinya Tsukamoto) finds himself suffering with TB on the Philippine island of Leyte where supplies, and tethers, are running short. Shortly after being punched in the face by his commanding officer, he’s given five days’ worth of supplies and ordered to march to the field hospital for treatment as no one wants a sick man weighing down the unit. Only, when he finally arrives at the field hospital, they have their hands full (literally) with the battlefield wounded. Marching back to his unit again, Tamura is ordered back to the field hospital and told to use his grenade to ease the burden on his fellow soldiers if refused. So begins Tamura’s fevered, mostly solitary odyssey across the beautiful landscape of the Philippine jungle suddenly scarred with corpses, the starving and the mad.

Tsukamoto’s adaptation sticks closer to the original novel than Ichikawa’s 1959 version, though both eschew Ooka’s Christianity. Tamura is a man at odds with his fellow soldiers. Formerly a writer he’s “an intellectual” as one puts it, and a little on the old side for a corporal. Coughing and wheezing, he shuffles his way through just trying to survive. Unlike Ooka’s original novel in which the protagonist’s Catholicism makes suicide an unavailable option, it’s the memory of Tamura’s wife which stays his hand on the pin of his grenade. Tamura wants to go home, to escape this hellish island full of the walking dead, hostile locals and hidden clusters of enemy troops.

To get home, to survive, what will it cost? There was barely any food left to start with. The original five days’ worth of rations Tamura was given amounted to a handful of yams. On his second trip to the military hospital he was given nothing at all. There’s no wildlife, even if you manage to find some plant roots they’ll need cooking. Of course, there is one abundant source of food, except that it doesn’t bear thinking about. Tsukamoto’s version takes a less ambiguous approach to the idea of cannibalism than Ichikawa’s which removed Tamura’s moral dilemma by having his teeth fall out through malnutrition and rendering him unable to indulge in “monkey meat” even if he might have succumbed. Death feeds on death and there’s no humanity to be found here anymore where men prey on men like animals.

There’s no glory in dying like this. Half starved, half mad and baking to death in the heat of a foreign jungle abandoned by your country which cared so little for its men that it never thought to conserve them. When you make it home, if you make it home, you aren’t the same you that left. The things you had to do to get there stay with you for the rest of your life, and not just with you – with all of those around you too. Wars don’t end when treaties are signed, they survive in the eyes of the men who fought them.

A timely and a visceral look at the literal horror of war, Tsukamoto’s Fires on the Plain is a refreshingly frank, if stylised, examination of the battlefield. Limbs fly, heads explode, organs are exposed and brain fragments leak out of ruined corpses. At any other time, Leyte would be a paradise of lush vegetation, colourful flowers and beautiful blue skies but it’s corrupted now by the fruits of human cruelty. This is what it means to go to war. There’s nothing noble in this – just death, decay and eternal grief. Though the film often suffers from its low budget and some may be put off by the stark, hyperreal cinematography, Fires on the Plain is another typically troubling effort from the master of discomfort and comes as a warning bell to those who still think it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.

Reviewed at Raindance 2015.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

First published by UK Anime Network.