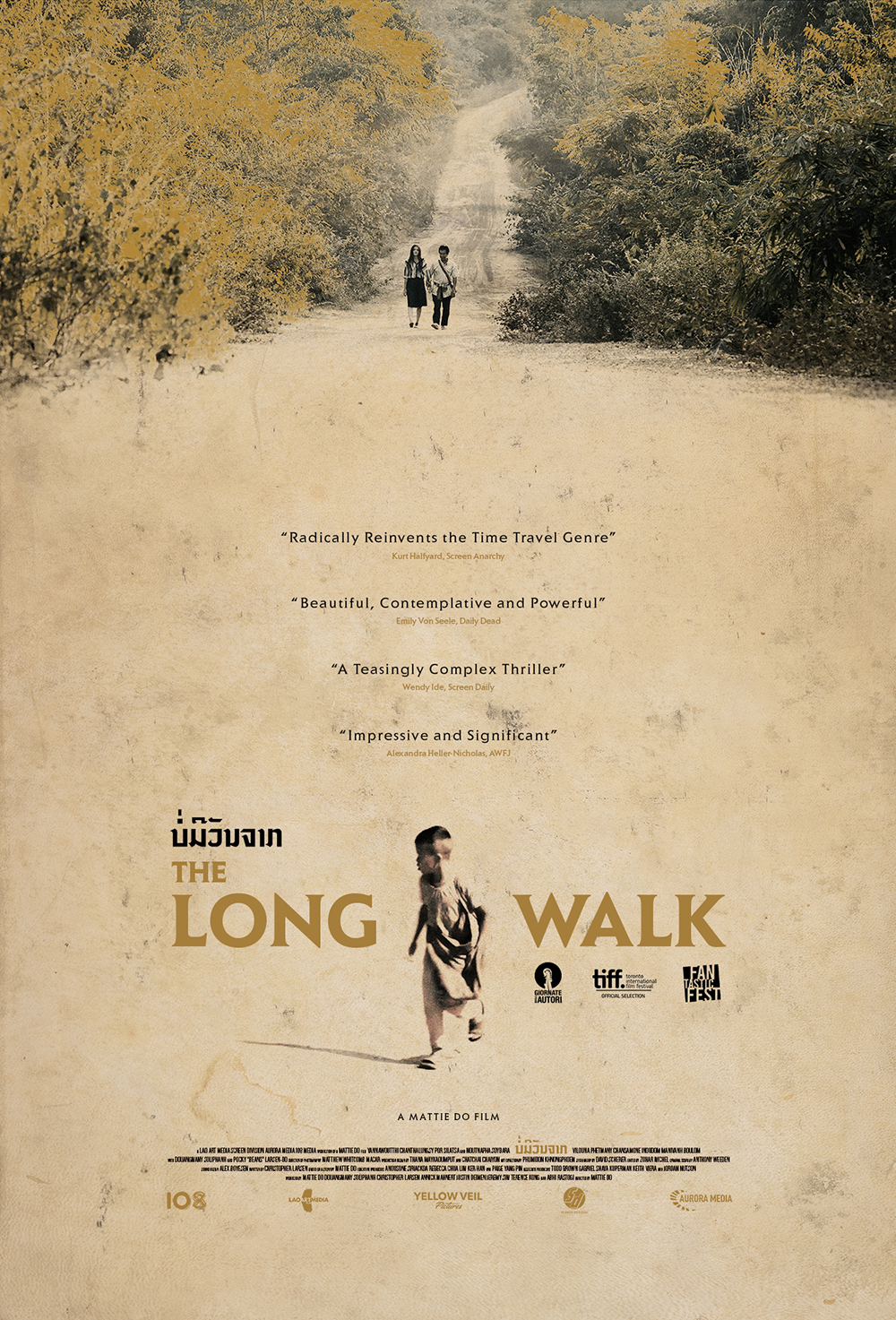

“How long have we been walking this road? Is it 50 years already? And you’ve never said a word” an old man (Yannawoutthi Chanthalungsy) reflects on reuniting with a ghostly presence (Noutnapha Soydala) that has accompanied him for almost all of his life if silently. An elliptical ghost story, Mattie Do’s The Long Walk (ບໍ່ມີວັນຈາກ, Bor Mi Vanh Chark) is indeed about the meandering path we all must take but also a meditation on grief and loneliness and what it means to die.

Beginning in the near future around 50 years from now, the film opens with an old man literally looting his past freeing an old motorbike before nature can reclaim it so he can take it apart and help it move on to its next life with a little help from the local pawn broker. Though life in this small rural village might not be so distinguishable from that of 50 years previously or even 50 years before that, modernity has crept in with transactions largely carried out via an embedded chip in the forearm which can also tell the time. On his arrival in town, the old man begins to hear a rumour that the old lady who ran the local noodle shop and had apparently been suffering with dementia has gone missing with the worry being that she may have ventured into the forest and become lost as perhaps has the old man if in a less literal sense .

The old man is well-known locally for the ability to contact spirits often spotted on the road chatting to his ghostly companion whom no one else can see, but as we come to understand his personal cosmology may in a sense be problematic in that the presence of a ghost is like a bug in the system, something trapped in the wheel of time that shouldn’t really be there impeding its movement. The old man knows the noodle seller is dead because he found her body and moved it to be closer to other departed spirits telling her that she will never be alone again, but in doing so he’s unfairly holding on to something that should be let go for the benefit of all. The first ghost, his constant companion, is that of a young woman he found dying in the woods when he was just a child (Por Silatsa), holding her hand until she was gone. In a sense he has never let it go nor she his.

Nearing the end of his life, the old man’s philosophy has hardened while he himself begins to fear for his own mortality drawn back into the past towards the early bereavement of his mother’s death. We might in a sense read his increasing confusion as a sign of dementia, that he’s trying to reorder a reality of which he is no longer certain while attempting to change his history with the help of his companion who is able to transport him back into the past in the hope that he can ease the pain of his childhood self while in roundabout way bringing his mother into his own old age so that he himself will not be lonely.

What he discovers, however, is that his interventions send the world in a darker direction than he’d expected in which he discovers unpleasant truths about himself eventually coming to realise the fallacy of his life’s philosophy. “I never helped any of those women” he sighs, “they suffered more for it”, acknowledging that he trapped these lost souls in a kind of limbo in which he is also is mired in preventing them from “moving on” forced on a circular journey caught between life and death.

At heart a tale of grief, loneliness, and guilt, The Long Walk also hints at the fracturing bonds between people in an increasingly modern society in which everyone is technically connected at all times via the chips embedded in their forearms now essential for everyday life. Looking back on his childhood, the old man remembers his father trying to take advantage of a scheme run by a foreign company supposedly to help farmers that only leads to getting solar panels installed on his farm which are in fact completely useless to him when all he wanted was a tractor, their lives had no need of electricity and its arrival benefitted them not at all.

Meanwhile, the old man is resentful towards the noodle seller’s daughter (Vilouna “Totlina” Phetmany) for neglecting her elderly mother who was all alone and could no longer care for herself, she having left for the city never to return possibly because as we later find out she feared that her sexuality may not be accepted in the still traditional community. The old man thinks he’s helping people escape lives of loneliness and despair by giving them a painless eternity but in reality his actions are merely self-serving, attempting to hold on to something that should have been set free. Dreamlike and elliptical, Do’s meandering tale is part ghost story and part time loop conundrum, filled with the beauty of nature but also all of its pain and terror in the ever present shadow of mortality.

The Long Walk is available now in the US on VOD courtesy of Yellow Veil Pictures and will be released on blu-ray on March 29.

Trailer (English subtitles)

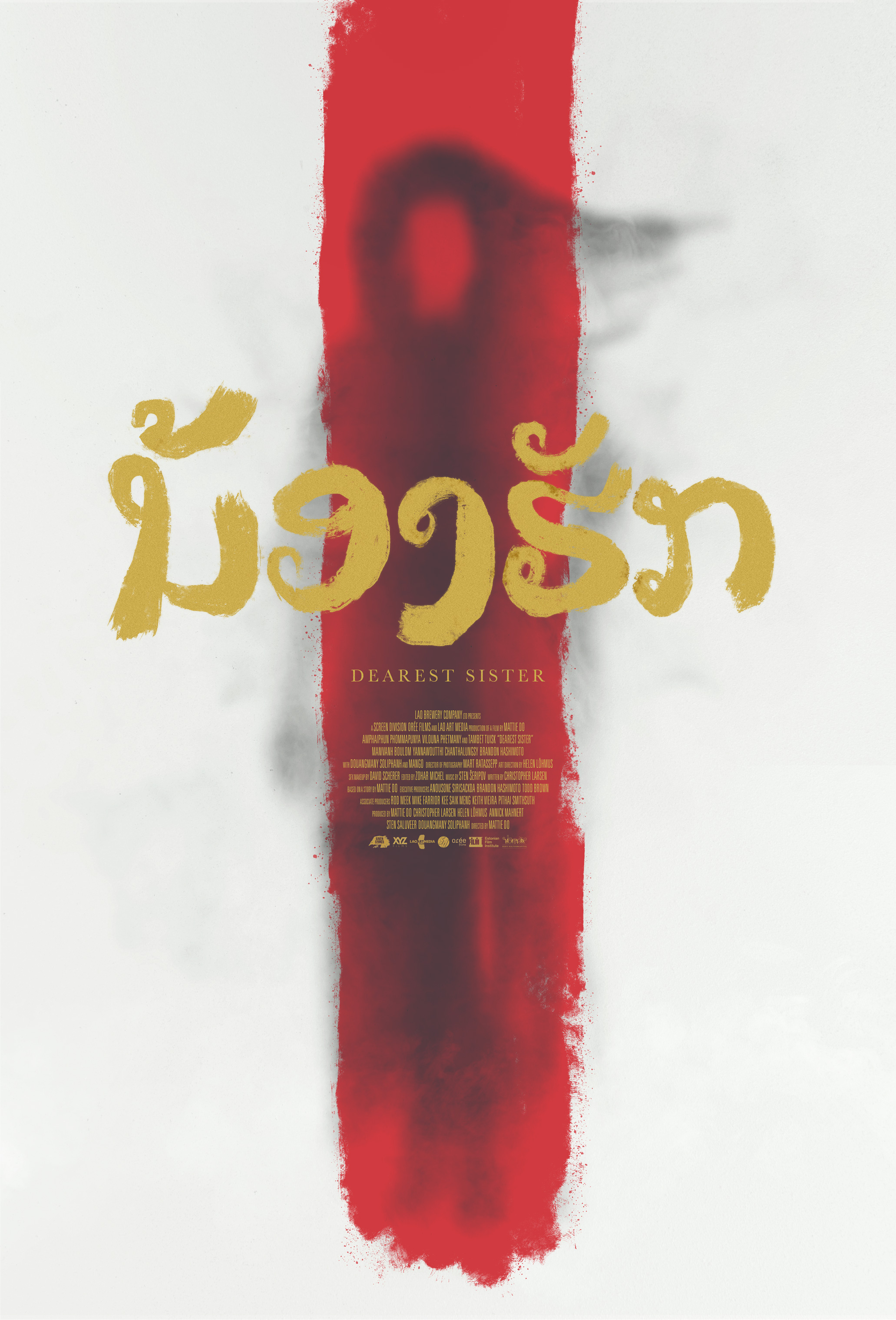

Marxist countries and horror movies often do not mix. Laos has only a fledgling cinema industry and Mattie Do, returning with her second film Dearest Sister (ນ້ອງຮັກ, Nong hak), is its only female filmmaker even if she finds herself a member of an extremely small group. Set in Laos it may be, but Dearest Sister also has something of the European gothic in its instantly recognisable tale of a good country girl fetching up in the city only to be treated like a poor relation and eventually corrupted by its dubious charms. Dearest Sister is a horror movie but one which places very real fears, albeit ones imbued with superstition, at the forefront of its tragedy.

Marxist countries and horror movies often do not mix. Laos has only a fledgling cinema industry and Mattie Do, returning with her second film Dearest Sister (ນ້ອງຮັກ, Nong hak), is its only female filmmaker even if she finds herself a member of an extremely small group. Set in Laos it may be, but Dearest Sister also has something of the European gothic in its instantly recognisable tale of a good country girl fetching up in the city only to be treated like a poor relation and eventually corrupted by its dubious charms. Dearest Sister is a horror movie but one which places very real fears, albeit ones imbued with superstition, at the forefront of its tragedy.