“All humans are entertaining,” or perhaps “interesting” at least to the producer of a variety TV programme who later admits that he may have a kind of detachment that allows him to bypass normal ethical concerns or responsibilities towards others. His words may at first seem egalitarian or humanistic, but they also point to a commodification of the human spirit in which the everyman is merely a figure liable for exploitation by a puppet master like the later remorseful Tsuchiya.

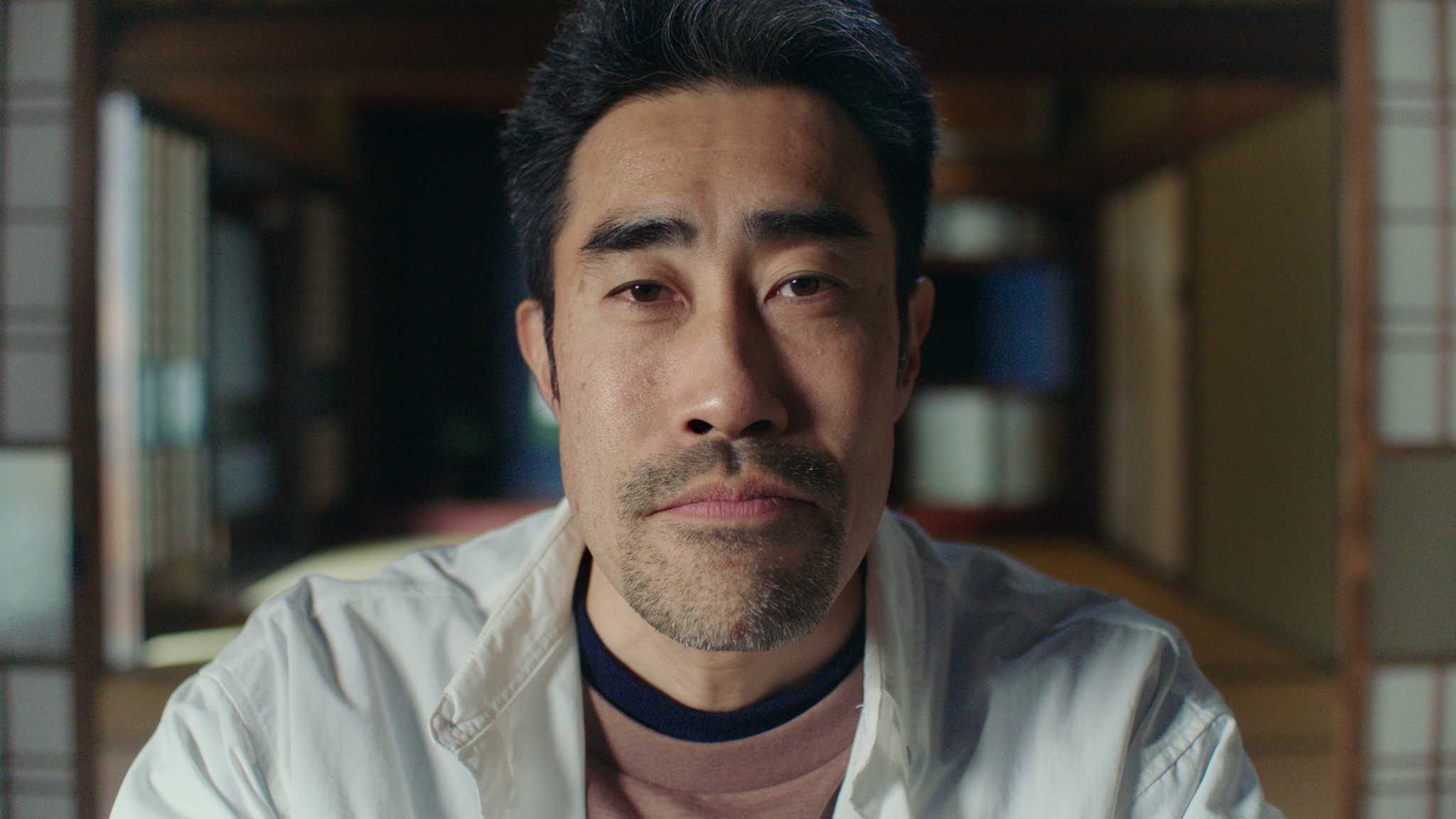

Clair Titley’s documentary character study The Contestant explores the birth of reality television in a Japan still mired in malaise following the collapse of the bubble economy asking both why someone would put themself through so much degradation and indeed why others would find their humiliation entertaining. From an audience perspective, there may be an assumption that Nasubi, the titular contestant, conceived this idea himself and is entirely consenting to the way he’s being treated but as he explains Nasubi had simply attended an audition to appear on popular variety programme Denpa Shonen and had no idea what was going on. Selected by lottery, he was led away by Tsuchiya and installed in a studio apartment where he was told to strip and that he was now taking part in a skit to see if someone could live solely on prizes won from magazine giveaways. He knew that he was being filmed, but was given the impression the footage would not air on television and was presumably intended for another purpose once the project was over. His ordeal would last more than a year.

As is repeatedly stated, Nasubi was never a prisoner. The door was always open and he could have chosen to leave at any time but did not do so. Asked why this is, why despite malnutrition and the possibility of starvation, the humiliation of being forced to eat dog food, the loneliness and isolation, an older Nasubi reflects that when you become so mentally and physically broken leaving no longer occurs to you. He considered suicide many times, but never simply walking out the door.

The irony is that audience satisfaction is largely derived from Nasubi’s “happiness” in his overjoyed reactions to finally winning something. Edited down to a weekly digest, the programme includes only such happy moments rather than the crushing sense of futility and loneliness Nasubi recounts in his diaries which also become, unbeknownst to him, best sellers. A British BBC correspondent explains that the show was popular with younger people and less so with the older generation who remembered post-war privation and simply did not find the idea of a man facing starvation alone, naked, in a tiny apartment very funny nor did those who were suffering economically themselves.

Equally, some perhaps feel that as it’s only a TV show it isn’t really “real” and so it can’t really be affecting Nasubi in a negative or long-lasting way even if what’s really happening is more like torture at the hands of an out of control media puppet master who admits he didn’t really know what he was doing and was simply trying to push things as far as they would go without actually killing their subject. The film presents Tsuchiya and Nasubi as two sides of the same coin, both sons of policemen who were forced to move around a lot as children because of a common practice in Japan to rotate law enforcement officials and other civil servants to different areas every few years as a means of preventing corruption. Nasubi reveals that he got his nickname, “aubergine”, from the kids who bullied him at every new school objecting to his long face. Gradually, he developed the defence mechanism of making people laugh so they wouldn’t bully him. This might explain why he responds to what extends to sustained harassment from Tsuchiya by increased mugging for the camera, while Tsuchiya by contrast agrees that his childhood experiences have left him “detached” and unable to make deeper connections with other people.

In some senses, it’s possible to think of reality television as frustrated bid for connection and that like his childhood self Nasubi is trying to gain control by owning the joke only to later feel damaged and traumatised by his experiences, insisting that the way Tsuchiya in particular treated him caused him to lose faith in humanity and left an unfillable void in his heart. The surprising thing is that unlike Tsuchiya, who later seems to accept that his actions were unethical and exploitative, Nasubi does not become cruel or embittered but finally finds a way to heal himself in helping others especially the people of his hometown, Fukushima, after the devastating earthquake in 2011. Though he admits it would be impossible not to harbour resentment towards Tsuchiya for everything he put him through, he also believes that the experience gave him something very special in showing him that no one can survive alone and granting him a better understanding of the importance of humanity and the spirit of supporting each other.

Titley captures the sense of anarchism in late ‘90s variety with brief clips of the extreme onscreen graphics which have informed modern meme culture, even suggesting ironic use of an aubergine to cover Nasubi’s modesty may have given rise to the current use of the emoji. To dampen the sense of overstimulation which can often occur with these kinds of programmes, she dubs some of the original voiceover and replaces text with English in the same kinds of crazy fonts often employed in variety shows but is always very careful not to exoticise the content or imply these are things that only happen in “wacky Japan” but instead sensitively explores how Nasubi was able to find something positive in the midst of an incredibly traumatising situation and use that to lead a more fulfilling life despite those who may still try to mock or belittle him.

The Contestant screened as part of this year’s DOC NYC.