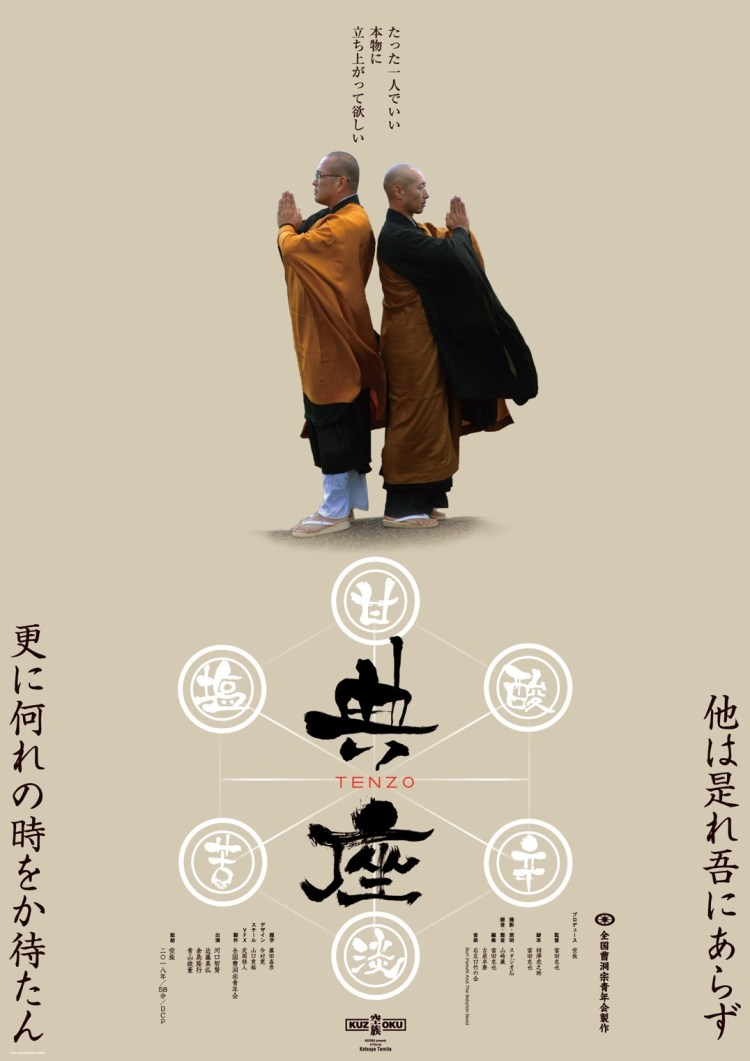

If you think the world has declined, how should you continue to live in it? The monks at the centre of Katsuya Tomita’s documentary hybrid Tenzo (典座 -TENZO-) have committed themselves to living intensely in the moment, following the teachings of zen master Dogen and embracing the uniqueness of each and every day even in its banality. But the search for truth necessarily takes one away from demands of daily living, from the entrenched suffering that pushes record numbers of people towards suicide and leaves others feeling as if they have no hope for the future.

If you think the world has declined, how should you continue to live in it? The monks at the centre of Katsuya Tomita’s documentary hybrid Tenzo (典座 -TENZO-) have committed themselves to living intensely in the moment, following the teachings of zen master Dogen and embracing the uniqueness of each and every day even in its banality. But the search for truth necessarily takes one away from demands of daily living, from the entrenched suffering that pushes record numbers of people towards suicide and leaves others feeling as if they have no hope for the future.

Monk Chiken once felt hopeless himself. In Japan, temples are a family business and it is expected that the oldest son will succeed whether he feels any call to religion or not. Chiken, as a young man, did not and resented his lack of choice in his future, but eventually came around to the idea of being a monk in part in recognition of a need for increased spiritual support in a nation he, and others, felt to have lost its way. 10 years previously, he spent some time in a monastery before returning home, getting married, and becoming a father.

At a loss for what to do, Chiken decided to bring temple food to the people by holding cookery classes as a kind of local outreach project. Believing that food is medicine which nourishes the soul as well as the body, he hoped to help repair the connection between people and nature. He also believes, perhaps privately, that the gradual decline of the environment has contributed to his son’s serious allergies and that though a wholesome diet may help, it may not be enough to prevent him coming to harm.

Other ways he tries to help include taking calls from people in distress and listening to their troubles. Chiken is part of a collective of local monks helming a helpline in the Fukushima area for those who want someone to talk them out of taking their own lives. That’s not to say, however, that being a monk necessary makes one free of troubles. Chiken occasionally resents himself for not being there for his family, snapping at his wife and unable to visit his son in the hospital because of ceremonial duties. Faced with a call from another monk on the helpline, he simply doesn’t answer. The other monk, Kondo, retreats to a nearby window and vapes while staring at the moon, proving that monks are regular people too who drink and smoke and live their lives while continuing to search for the truth.

For some, however, the rug has been unexpectedly pulled from under them, making any sense of truth they may have discovered seem hollow. Ryugyo, like Chiken, was the son of a Buddhist priest but he lost his family temple to the earthquake and nuclear disaster. Still living in cramped temporary housing, he makes ends meet as a construction worker, occasionally visiting some of his old neighbours in the place of a monk while lobbying to get the funds together to build a new temple. Originally not sure he should be part of the helpline seeing as he’s no longer, technically speaking, a monk he finds himself pouring out his troubles to a stranger.

Chiken, meanwhile, finds himself branching out in his search for truth – heading to Shanghai and Dogen’s temple looking for guidance towards a way forward. He meets with an esteemed nun who tells him that his youthful sense of rebellion was only natural and probably a good thing because becoming a monk should be a choice not an obligation. She laments that Buddhism in Japan has become “corrupt”, that the demise of the old apprentice system in favour of patrilineal inheritance has led to a decline in rigour. Chiken feels as if it’s the world which has declined, that the post-war drive towards economic stability and its eventual implosion have resulted in an empty consumerism which is contributing to an ongoing sense of hopeless malaise. Trapped in a limbo of his own Ryugyo may feel something similar, wondering how to rebuild while conducting lonely services over ruined graveyards. What they do is return to Dogen, living in the everyday and continuing to look for truth to counter the meaninglessness of the consumerist society.

Screened at the ICA as part of their Katsuya Tomita retrospective.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Reworked from a review first published by

Reworked from a review first published by