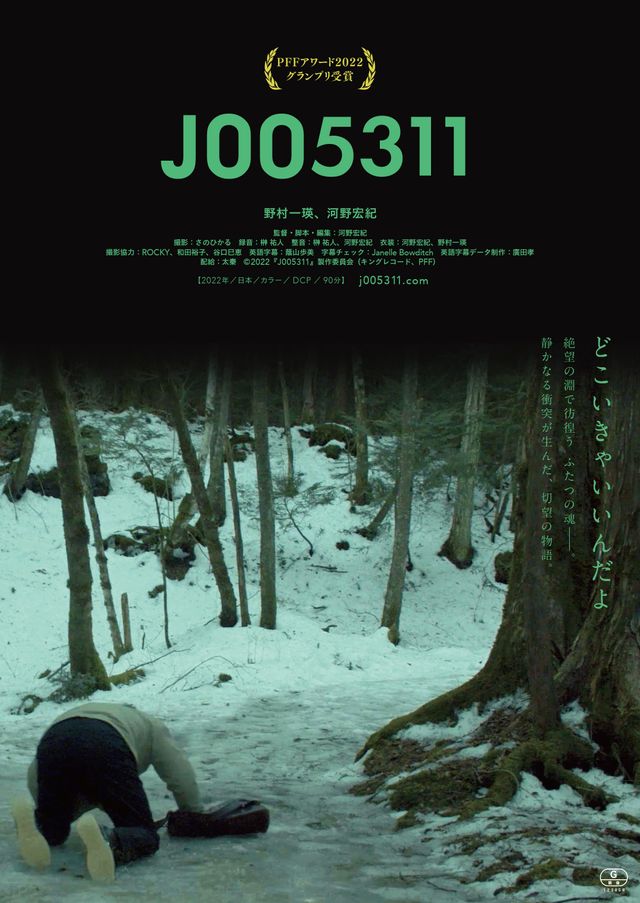

If a stranger offers you a large amount of money to drive to an undisclosed location, what would you say? Hiroki Kono’s J005311 is so named for a bright new star born when two stars already dead collided which goes some way to explaining the central relationship between the two men at the film’s centre. Though they rarely speak, a kind of connection arises between them that changes them both in unexpected and unexplained ways but perhaps gives each a new sense of hope and possibility.

After some kind of alarming phone call, Kanzaki (Kazuaki Nomura) throws away various things in his apartment and leaves as if not expecting to return. He goes out and tries to hail a cab, but it seems as if the driver refuses to take him where he wants to go. Kanzaki slowly walks away and sits down wondering what to do next before catching sight of a young man running furiously across the road after snatching a woman’s handbag. Kanzaki wouldn’t usually be the sort to chase a thief, but tears off after the man and makes him a rather unexpected offer. He will pay him a million yen if only he’ll agree to drive him to a location near Mount Fuji around two hours away. The man is understandably suspicious and in fact tries to snatch the bag Kanzaki had the money in but is ultimately unsuccessful and agrees to the drive.

No real explanation is given for why Kanzaki is prepared to pay this large sum of money to get someone to drive him rather than taking public transport at least part of the way or booking a car through some kind of chauffeuring firm where long fares are more usual. It may be because he’s afraid whoever called him will find him on a train or bus, which would also explain why he leaves his phone behind at a service station, or perhaps he just wants company and companionship on what is looking increasingly like a final journey. Kanzaki tells the man, Yamamoto (Hiroki Kono), that he’s going to meet “a friend” which is a fairly unimaginative lie he doesn’t believe for a second though he for the moment he lets it go. Later Yamamoto notices he has a rope in his bag while we also see Kanzaki loop its strap around his neck and try to strangle himself all of which adds grim import to his final destination.

For his part, Yamamoto is wary of the arrangement and also of Kanzaki who is awkward in the extreme. He tells Kanzaki that he can buy whatever he likes with the million yen yet when he asks what he’ll use it for he says he doesn’t know. He says he likes work that’s “easy” like construction or deliveries while evidently supplementing his income with the purse snatching which he remarks gets easier each time you do it. Several times it seems as if Yamamoto may run off with the money, or just run off leaving Kanzaki stranded, but eventually comes back if for unclear reasons that nevertheless suggest he’s begun to care Kanzaki and feels to an extent responsible for him while fearing what awaits him at his destination.

Kanzaki too feels responsible for Yamamoto, eventually asking him to give up bag snatching as if implying that he’s better than that and ought to respect himself more. After tipping copious amounts of sugar onto his food at a rest stop, Kanzaki shoves a whole pastry into his mouth and seems as if he’s about to cry perhaps feeling rejected or that he overstepped the mark with Yamamoto before suggesting that he might want to walk the last part alone only for Yamamoto to once again return and follow him. In a sense they begin to save each other, bonding in a shared sense of despair if exchanging few words and emerging with a new sense of possibility forged by their unexpected sense of connection. Kono follows the two men with restless intensity, the camera swooping POV style or clinging tightly to them in the confines of the rented car while eventually seeming to vibrate in the poignant closing scenes. At times obscure, the film nevertheless has a wintery poetry and melancholic soul and ends on a note of silent serenity as the two men prepare to move on though who knows where to.

J005311 screened as part of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.