In the opening title sequence of Eizo Sugawa’s Beast Alley (けものみち, Kemonomichi), a thick blob of inky blackness gradually expands over an aerial view of the city until it obscures it entirely. The title card which then appears is written in plain white, but will reappear at the film’s conclusion this time ashen as if it too had been singed by the deeply ironic flames with which the film ends. Based on a novel Seicho Matsumoto and scripted by The Beast Shall Die’s Yoshio Shirasaka, the film similarly takes an incredibly cynical view of the modern post-war society in which it is revealed the militarists are still basically in charge and presiding over a deeply corrupt social order.

The big bad, Kito (Eitaro Ozawa), says as much when he states the need for reforming the nation’s “rotten political system” by which he means post-war democracy. Kito made his made his money doing deeply dodgy things in Manchuria in addition to running an exploitative coal mine in Japan. Now mainly bedridden, he basically runs the country as a far-right political fixer working in tandem with big business and the yakuza who have traditionally been big supporters of conservative and nationalist forces. Early on we see one of his underlings negotiating with politicians to ensure that Taiyo Roads will be hired be hired for a large scale construction project planning to put highways all the way through Tokyo. As we later discover, he’s prepared to go to great lengths in order to achieve his goal, going so far as to have a sex worker murdered to implicate the uncooperative CEO of a rival construction film into resigning by threatening to frame him for the crime so they can install their stooge in his position.

It’s into this world that everywoman Tamiko (Junko Ikeuchi) is drawn while working as a hotel maid at a traditional Japanese inn. Trapped in a bad marriage to a man who is also bedridden yet still attempts to rape her when she returns home to find him in bed with the housekeeper, Tamiko longs for escape and is therefore ripe for the picking when approached by Kotaki (Ryo Ikebe), the manager of an upscale Western hotel, to join him in an unspecified enterprise which will apparently make her very rich. The only catch is that she will have to “get rid” of her “dependent”, which she probably wanted to do anyway, by burning down her house with him inside it. Once she’s done this, there is no turning back for her even if she had not developed complicated feelings for Kotaki who is both her salvation and damnation.

Tamiko’s husband had failed to give her the comfortable life that he had promised, something which she thinks Kotaki can deliver even if it requires her to become the plaything of Kito whom does she actually seem to like even if aware of the precarity of her position and still in thrall to Kotaki. Leaving the hotel so abruptly was however a strategic error as it arouses the suspicious of (originally) earnest cop Hisatsune (Keiju Kobayashi) who quickly realises that Tamiko set the fire to kill her husband. Though he seemed to be motivated by justice, Hisatsune too is soon corrupted explaining to Tamiko that he has become cynical and jaded. Years of police work have shown him that true criminals know how to break the law and get away with it so he can’t do anything about them, but “good” people, like he implies Tamiko, are pushed into crime by desperation and are easily caught. Tamiko wields her sexuality against him by agreeing to a tryst, though when it doesn’t go to plan he tries blackmail and then rape before she, ironically, manages to escape from his bungled crime.

Hisatsune’s corruption is gradual and self serving. He starts with suspicion, tailing Tamiko in the interests of justice but also because he desires her, before stumbling on the conspiracy, putting the pieces together, attempting to use them for his own gain and trying to blow a whistle mostly out of resentment. Kito’s reach is all encompassing. Hisatsune is warned off investigating certain aspects of the crime by his senior officers and is then fired on Kito’s instructions for fiddling his expenses after harassing Tamiko. He tries to give his findings to his boss but it goes nowhere and then tries the press but is given the brush off, the editor his reporter friend refers him to gently implying he’s just a crank with an axe to grind. Of course, it turns out that the reporter is already in league with dodgy lawyer Hatano (Yunosuke Ito) who is Kito’s right-hand man.

The connections between the three men, Kotaki who was once a communist, Hatano, and Kito go back to Manchuria and the corruptions of militarist era which it becomes clear has never really ended. Kito has only one rival and it’s another faction of the conservative ruling party who are probably just waiting for him die. Attempts are made on his life and they don’t go well for those who make them. Even if Hatano hoped to simply inherit an empire he, as he points out, put in much of the work to build he is sorely mistaken while Tamiko may intellectually understand that Kito’s death would place her in a precarious position but carries on regardless. “You never know who will betray you in this world” Kotaki laments, echoing Kito’s later claim that his Buddhist statues are the only ones will never betray him even as sleeps next to a statue of Aizen Myo whom he ironically claims protects mankind from their lust and desire.

It could be said that desire is Tamiko’s undoing, but as Hisatsune had suggested perhaps you couldn’t blame her for longing to be free of the bedridden husband who had not delivered what he promised her. As she said, she was doing what could to survive even if you’d think she’d know putting on a ring taken from the finger of a murdered woman is akin sealing your own fate. Sugawa shoots with a noirish sense of dread, tracking Tamiko with her coat drawn up around her face as she tries to leave the scene of her crime, and makes the most of his fiery imagery before ending on a note of cynical laughter amid the inescapable hell the of post-war society.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

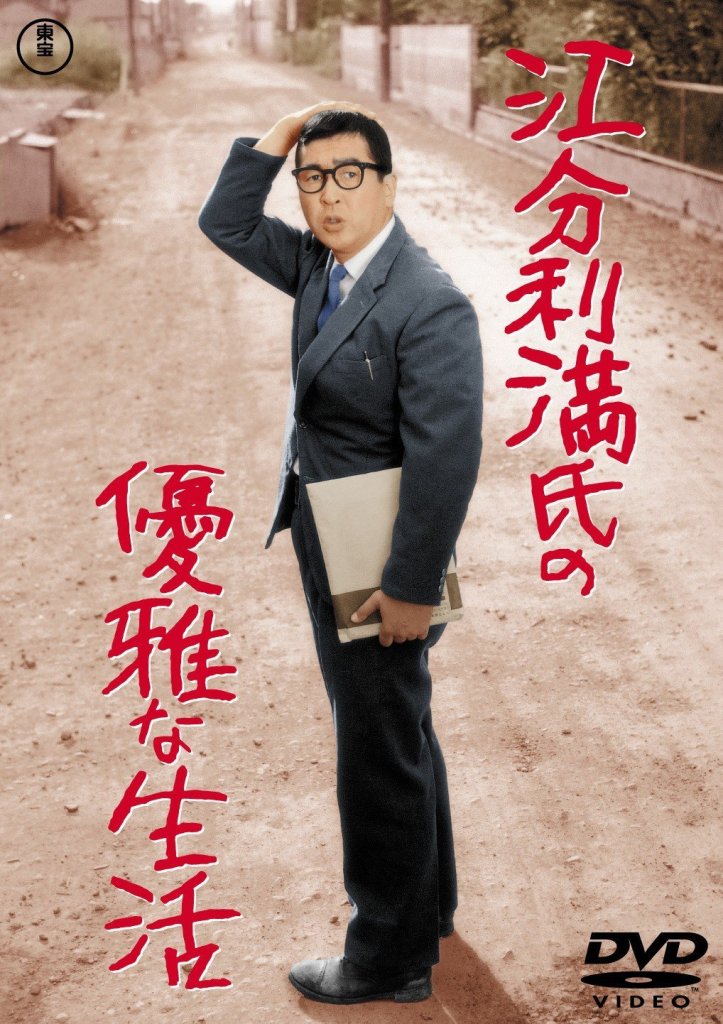

Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour.

Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour.