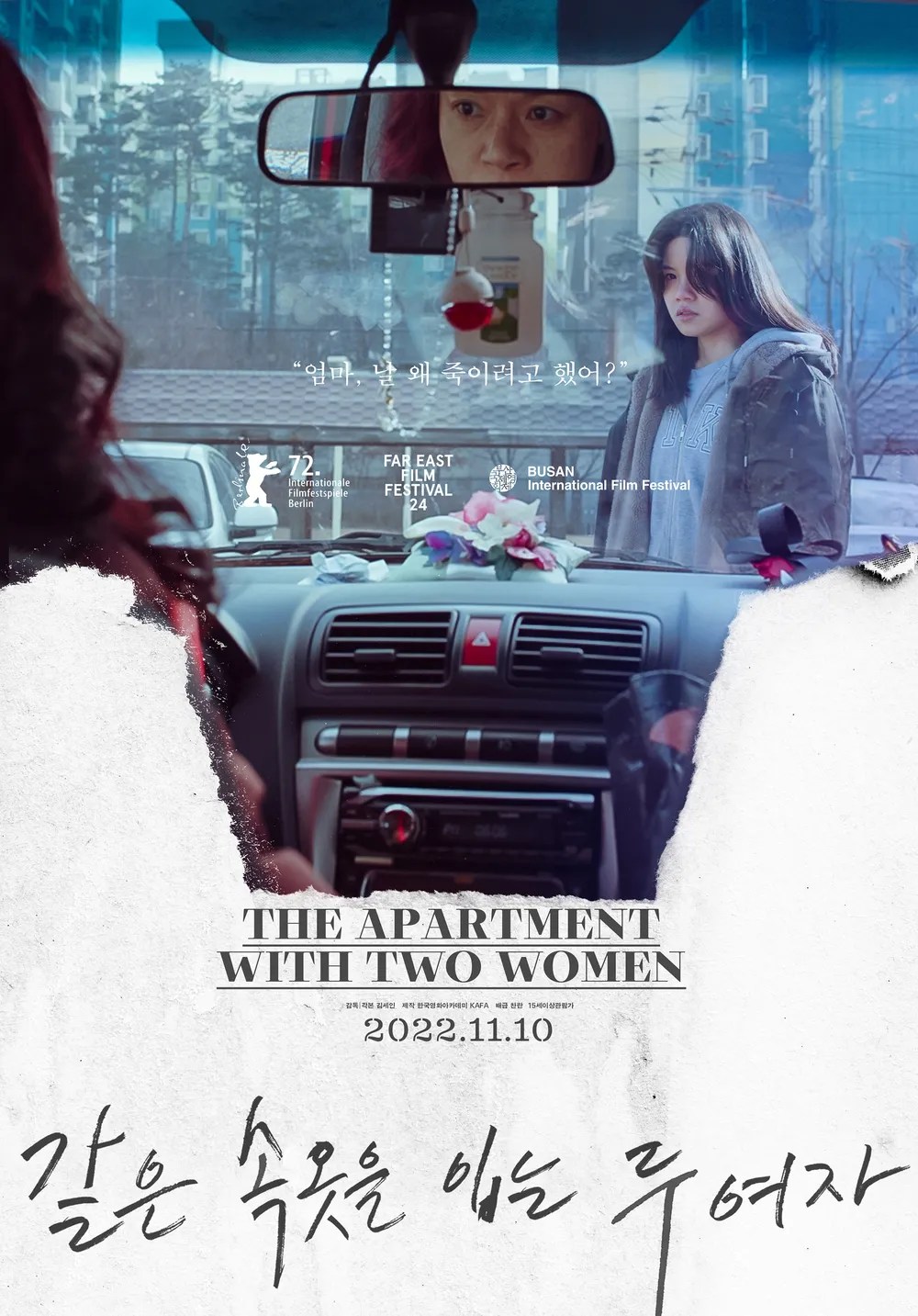

A mother and daughter remain locked in a toxic cycle of resentment and dependency in the debut feature from Kim Se-in, The Apartment with Two Women (같은 속옷을 입는 두 여자, gateun sogoseul ibneun du yeoja). While the English title may have an unfortunate sexist connotation implying that such a dysfunctional relationship is inevitable when two women live together, the Korean “two women wearing the same underwear” more closely suggests the awkward intimacy between them as they each seem to seek escape from the other but in the end are left with no option than to return or choose independent loneliness.

The awkwardness is obvious from the opening scenes as middle-aged, pink-haired mother So-kyung (Yang Mal-bok) chats to a friend on the phone while using the toilet even as her 20-something daughter Yi-jung (Lym Ji-ho) washes her undies in the bathroom sink. Once done, So-kyung slips off her underwear and simply throws them in with the others for Yi-jung to scrub, taking one of the newly washed but not yet dried pairs as a replacement before breezily leaving for work. So-kyung often becomes angry with her grown-up daughter for no ostensible reason, hitting and slapping her while a defeated Yi-jung can do nothing but cry no longer seeing much point in even asking what it is she’s done wrong. Matters come to a head when the pair argue in the car at supermarket car park. Yi-jung gets out and begins to walk away, but her mother suddenly jumps on the accelerator and hits her. So-kyung tries to claim the car malfunctioned but Yi-jung has long believed her mother would prefer it if she were no longer alive.

During a blackout towards the film’s conclusion, So-kyung again insists the accident wasn’t deliberate reminding that Yi-jung that it wasn’t the first time she swore she’d kill her and forcing her to admit that she remained so calm because it wasn’t the first time she’d heard it. Later someone asks why she didn’t leave seeing as she is a grown woman with a salaried job capable of supporting herself and she answers that she thought she needed to save more money before making her escape but it’s also true that years of So-kyung’s emotional abuse have eroded her confidence in her ability to survive alone and that finally she is just so lonely that even her mother’s continual resentment is preferable to being on her own with no other friends or family to turn to.

Yi-jung begins to bond with a woman at work who is in a similarly abusive situation with their employer, disliked by her co-workers and exploited by the boss who often hands her additional tasks to be completed for the next morning when everyone else is about to go home. But So-hee (Jung Bo-ram) evidently has troubles of her own, and in any case Yi-jung simply ends up in another apartment with two women while beginning to realise that So-hee is not interested in a close friendship with her for she too longs for “independence” and is turned off by her obvious neediness. So-kyung meanwhile is in a relationship with a genial man of around her own age, Yong-yeol, who has a teenage daughter, So-ra, to whom So-kyung more well disposed than to own but eventually cannot stand. So-ra is in many ways much like herself and So-kyung’s narcissistic tendencies prevent her from sharing Yong-yeol with another woman. When it comes to picking an apartment for them to live in after they marry, it comes as a surprise to her than Yong-yeol intended to bring So-ra to live with them roundly telling him that the “spare” room is for storage not a daughter. Given this ultimatum Yong-yeol choses So-kyung, agreeing that So-ra will live with her grandmother in a decision that shocks Yi-jung on discovering his letter prompting the realisation that her mother will happily abandon her too.

Su-kyung is in many ways a narcissistic nightmare, refusing to apologise for who she is and always insisting other people are to blame for the way she treats them. All Yi-jung wants is an apology but what she gets is justification as her mother explains to her that her clients at her massage parlour dump all their negativity on her though she is also living a stressful life and so she dumps all of her negativity on Yi-jung whom she resents for trapping her poverty and loneliness as a reluctant single mother. Yi-jung asks her what she’s supposed to do with that, but her mother simply tells her she should have a daughter too. In any case it appears as if Yi-jung may finally be finding the strength to extricate herself from her toxic familial environment, finally being measured to figure out her correct bra size having presumably been forced to wear whatever her mother wore throughout all of her adult life in a moment which brings us back to underwear once again. At times darkly comic, Kim Se-in’s intense family drama circles around toxic dependency and an inescapable cycle of cruelty and resentment but does at least allow its heroines the glimmer of new beginnings in a more independent future.

International trailer (English subtitles)