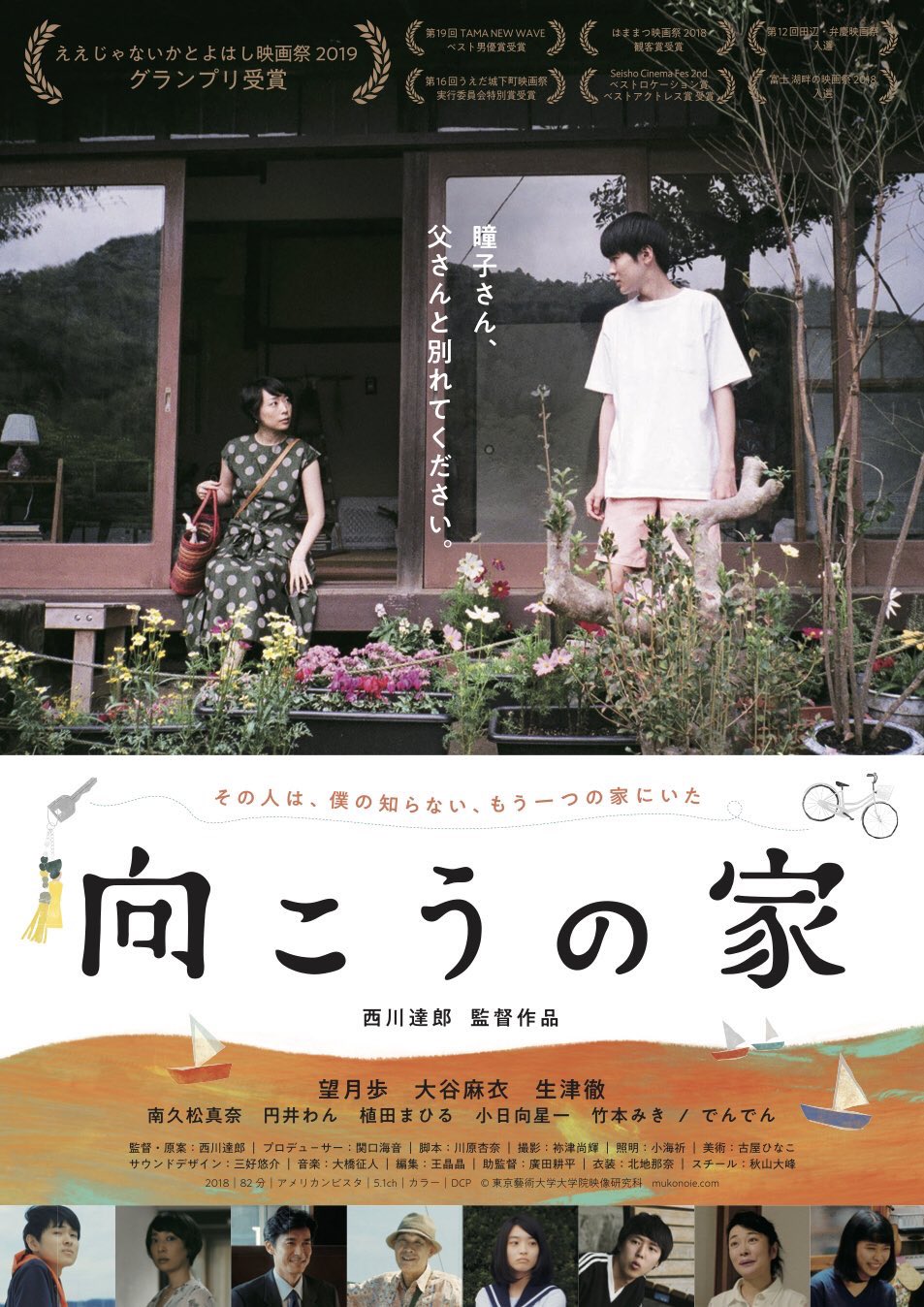

There comes a time in everyone’s life when they start to realise that things are not always as they appear and no matter how happy and settled your family life might seem, your parents aren’t perfect though they are probably doing their best. For Hagi (Ayumu Mochizuki), that moment comes at 16 when he gets fed up with school and takes some time off believing he might be able to learn more outside of the classroom than in. An unconventional coming-of-age tale, Tatsuro Nishikawa’s graduation project The Other Home (向こうの家, Mukou no Ie) is also a meditation on the modern family and the patriarchal order.

Getting back to school after the summer break gets off to a rocky start when Hagi and his friend are told that the fishing club of which they are members is being shut down as the teacher who was in charge of it is scaling back her workload because she’s just got engaged and will eventually be leaving to get married. Hagi takes this in his stride, mostly at a loss over where to eat his lunch because his girlfriend, Naruse (Mahiru Ueta), for some reason thinks it’s embarrassing to eat alone in the classroom. In any case, Hagi reacts by deciding not to go to school at all. His parents don’t approve, but decide to give him some space to figure out what’s going on. Meanwhile, he’s beginning to wonder if it’s odd that his family never fight, his parents committed to talking things through peacefully rather than resentfully hiding their true feelings.

Or, so he thought. There is something childishly naive in his conviction that because his parents never fight in front of him they never fight at all, though it’s true enough that he comes from a talking about things family in which his mother Naoko (Mana Minamihisamatsu), in particular, is keen that they share their thoughts and feelings honestly, looking forward to her husband Yoshiro (Toru Kizu) returning home each day after which they share a drink and make time to talk. It comes to something of a surprise to him then when his dad asks him to pick up a set of keys he’s forgotten and bring them to a cafe near where he works without letting his mother know. Hagi does as he’s told only to learn the keys are for a cheerful cottage by the sea which he’s been renting for his mistress, Toko (Mai Ohtani), with whom he now wants to break up preferably before the lease is due for renewal. Too cowardly to do it himself, Yoshiro enlists his teenage son’s help to break up with the woman he’s been cheating on his family with.

Strangely, this revelation does not seem to sour him on his dad even if he realises the threat it poses to their happy family life. “Protecting the family peace. Men must uphold that promise” Yoshiro unironically tells his son, problematically implying that the way to do that is by covering up affairs rather than simply not having them. Dutifully Hagi heads over to “the other home”, only to be thrown out by Mr. Chiba (Denden), a friend of Toko’s who not unreasonably tells him that this is something his father should be dealing with himself rather than sending his teenage son to guilt his mistress into moving out of her house. Failing to engage with his father’s betrayal, Hagi nevertheless comes to sympathise with Toko who is about to be rendered homeless thanks to his father’s moral cowardice, staying with her in the cottage while lying to his mother that he’s doing an internship at his father’s company.

Nevertheless, each of his parents is eventually found wanting as Toko teaches him the things they perhaps should have including how to ride a bike, an embarrassing oversight which had seen him deemed “uncool” by his exasperated girlfriend. The film has little time for Naoko’s talking about things philosophy, her husband merely lying to her while engaging in the same patriarchal double standards simultaneously insisting it’s a man’s duty to “protect family peace” while deliberately endangering it through an extramarital affair. Hagi too perhaps picks up these uncomfortably old fashioned ideas partly from his teacher who proudly shows off her engagement ring boasting that it cost her fiancé three months’ salary, the expense apparently proof that he intends to look after her well for the rest of her life as if she couldn’t do that herself. He begins to feel sorry for Toko as she outlines her life as a kept woman, a backroom full of unwanted presents from various men who too looked after her for a time, but in the end merely offers to look after her himself by quitting school to get a job so he can renew the lease to make up for his father’s moral cowardice.

The reason they were so happy, it seems, is that Yoshiro gave himself an escape valve. “Sometimes it’s hard for me to be dad” he admits, apologising for his inability to share his burdens honestly, his male failure neatly undercutting the tacit acceptance of the patriarchal authority which stands in contrast to Naoko’s ideal of a healthy relationship founded on emotional authenticity. Finally learning to ride a bike, Hagi finds himself entering a less innocent world as a young man now fully aware of the universe’s moral greyness if perhaps not quite so enlightened as he might feel himself to be.

The Other Home screened as part of Camera Japan 2020.

Original trailer (no subtitles)