“There is the vast realm of the unconscious,” one of the professors explains to vacant medical student Hiroshi a soon-to-be physician attempting to heal himself from a trauma he doesn’t fully understand. Perhaps as the title implies, Vital (ヴィタール) sees Tsukamoto branch out from his vistas of urban alienation to find a new paradise in nature albeit one that it exists largely in the mind and that the hero can never fully return to because this place of life is also one of death which exists inside a kind of eternity.

This explains to some extent Hiroshi’s (Tadanobu Asano) temporal confusion. Having lost his memory following a car accident in which he later learns his girlfriend Ryoko (Nami Tsukamoto) was killed, he shifts between “reality” and what first seems to be flashbacks of his unremembered past but are actually taking place in a kind of alternate, perhaps idealised reality in the “vast realm of the unconscious” as Hiroshi attempts to reconstruct his image of Ryoko along with that of himself. Another of his professors more philosophically asks were lies the seat of the soul in the human body and is this something that Hiroshi maybe unconsciously looking for during his anatomy classes in which he is coincidentally assigned Ryoko’s body to work on only realising when he sees her tattoo in one of his visions.

In some ways this grim task of dissection is a bid for greater intimacy, to take Ryoko apart and then put her back together as the students diligently do at the end their studies reassembling the bodies and placing them in coffins in keeping with culturally specific death rituals. The faces of the cadavers are covered with a bag until the students are instructed to remove them, but they are always reminded to treat the dead with dignity and that their role here is one of understanding as they attempt to work out not only how these people died but also how they may have lived. Hiroshi causes conflict with some of his fellow students on just this point, seeming rather creepy in his vacant intensity over the body while also wanting to take ownership over that of Ryoko rather than work as part of the group complaining that the others are too clumsy and it’s affecting his ability to learn.

Ryoko’s father comes to say that though he once blamed Hiroshi, his daughter had been in a way dead for a long time before she died, the light apparently going out of her eyes when she was still in high school. Only in Hiroshi’s unconscious does she say that she didn’t want to die despite an apparent obsession with death in Hiroshi’s other resurfacing memories/visions of her as symbolised in her repeated requests for him to strange her during in sex. Another of the professors had said that the suppressed desires of the unconscious could create conflict and this alternate reality is also in some senses Hiroshi’s own latent desire for death, to be with Ryoko in this new paradise that is founded on an idyllic beach rich with nature and sunshine where they are free to be together liberated from the oppressions of civilisation.

Indeed, it’s been raining all through the film as if in expression of Hiroshi’s gloomy mental state but we later learn that Ryoko’s most treasured memory was simply standing in the rain with him and breathing in its scent. Verdant nature is aligned with the vitality that is often absent from the soulless concrete of a city in which everyone seems to exist in tiny, separate worlds which only border on but never join each other. Ikumi (Kiki), a strange female student who develops a fascination with Hiroshi, has an illicit conversation with a professor she’s apparently been sleeping with each of them speaking into mobile phones while standing steps apart. Tsukamoto often isolates the protagonists, placing them in corners or blurring the periphery as if they alone existed in this moment. In Hiroshi’s idealised alternate reality, these barriers disappear as he and Ryoko share an entire world in love and freedom.

The irony is that he resurrects himself through the process of dissecting Ryoko’s dead body. His Da Vinci-like sketches begin to shift as do the ink-like shadows on the wall amid the reflection of the rain as Hiroshi stares vacantly trying to reassemble his past. Through accepting Ryoko’s death, he rediscovers life and is in a sense reborn insisting he will continue medicine even though his professor and parents advise him not to given what he’s just been through though his parents had also said that before the accident they didn’t really think he had it in him to become a doctor. Their disapproval may explain some of the pressures he was experiencing as perhaps was Ryoko that may have urged them to long for death. In any case, what the film presents is the archaeology of grief, a prolonged period of introspection and loneliness and a seeking of intimacy no longer really possible but discovered only in the vast realms of the unconscious.

Vital is released on UK blu-ray 30th September courtesy of Third Window Films.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

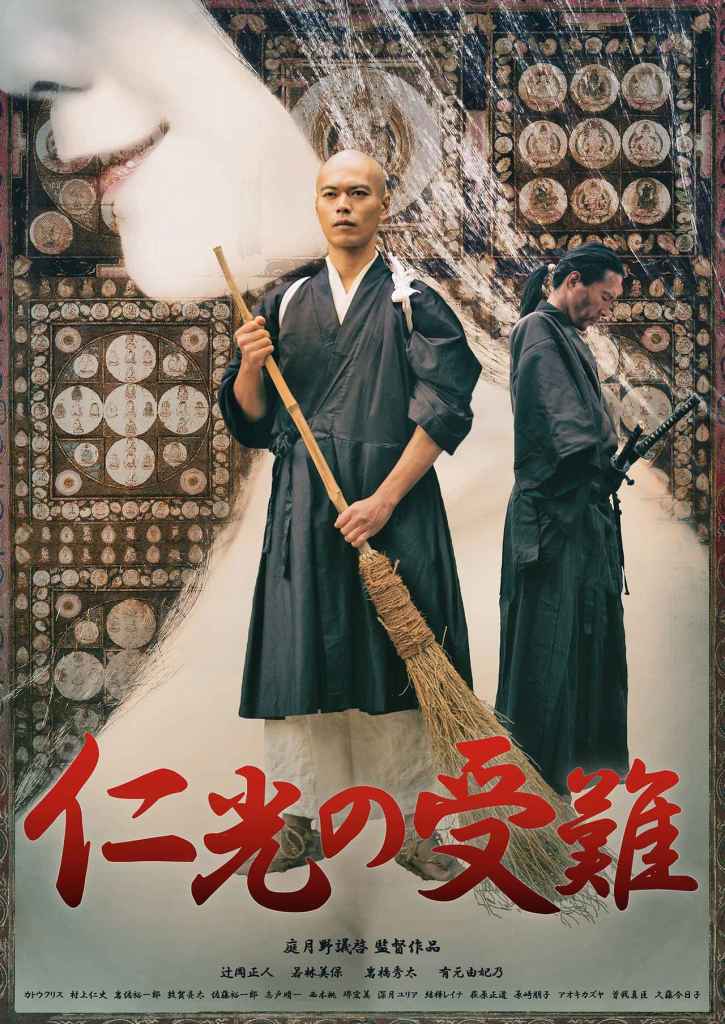

All life is suffering, and all suffering is caused by desire. Ninko, the titular monk at the centre of this entertaining oddity from Norihiro Niwatsukino, seems to have taken this to heart and is suffering more than most in his attempts to reach Nirvana. Suffering of Ninko (仁光の受難, Ninko no Junan) takes its cues from the Hyaku-monogatari classical Japanese tales of ghosts and the supernatural as its seemingly comic story of a pretty monk and his ironic talent for attracting the wrong kind of attention gradually darkens until its unexpectedly strange finale. Visually striking if a little rough around the edges, Suffering of Ninko has a pleasantly organic quality as if its narrator were really making it up as she goes along only to tire of it a little by the end and give us a suitably spooky conclusion to send us on our way.

All life is suffering, and all suffering is caused by desire. Ninko, the titular monk at the centre of this entertaining oddity from Norihiro Niwatsukino, seems to have taken this to heart and is suffering more than most in his attempts to reach Nirvana. Suffering of Ninko (仁光の受難, Ninko no Junan) takes its cues from the Hyaku-monogatari classical Japanese tales of ghosts and the supernatural as its seemingly comic story of a pretty monk and his ironic talent for attracting the wrong kind of attention gradually darkens until its unexpectedly strange finale. Visually striking if a little rough around the edges, Suffering of Ninko has a pleasantly organic quality as if its narrator were really making it up as she goes along only to tire of it a little by the end and give us a suitably spooky conclusion to send us on our way.