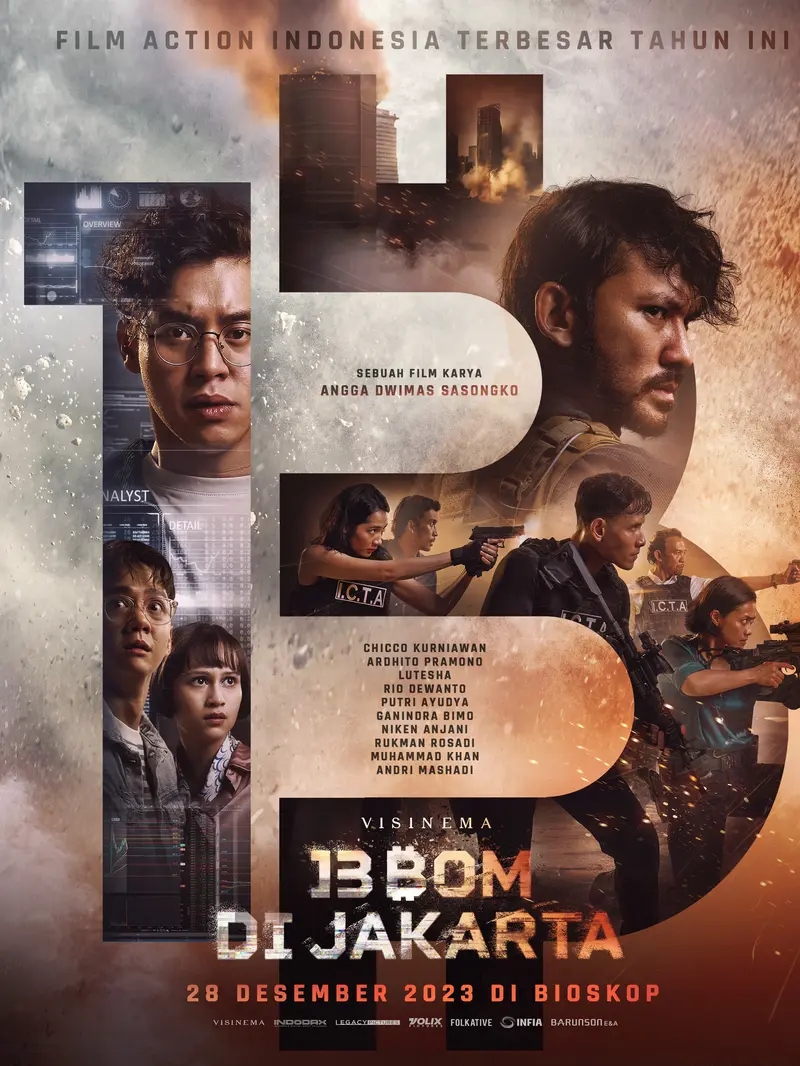

There’s an interesting juxtaposition in opening scenes of Angga Dwimas Sasongko’s action thriller 13 Bombs (13 Bom di Jakarta). A security guard in a cash van listens with exasperation to a radio broadcast voicing the nation’s economic decline before remarking that his mortgage keeps going up but his pay stays the same. Meanwhile, across town, two youngsters celebrate after receiving a huge payout from the cryptocurrency exchange app startup they’ve been running, drinking and partying oblivious to the poverty that surrounds them. Yet it’s the two youngsters that have unwittingly spurred a desperate man towards revolution, giving him the false idea of a utopia uncorrupted by money.

The interesting thing about the terrorists is that after attacking the cash van they blow the doors open and then leave without the money, allowing the people to pick it up instead. The explosion was apparently one of several more to come as the gang have placed 13 bombs around the city which they are holding to ransom, demanding to be paid in bitcoin solely through the boys’ exchange. The level of the crypto kids’ complicity is hard to discern, but it soon becomes clear they weren’t up for loss of life even if there’s a large payout at the end of it though they don’t really trust the police either.

The police, or more precisely, the Counter Terrorism team, don’t come out of this very well. They’re originally quite reluctant to view the incidents as “terrorism” because that will make everything very “complicated” and also worsen the already precarious financial situation. They also seem to be fairly blindsided, arguing amongst themselves about the proper course of action with the sensible and reliable Karin (Putri Ayudya) often shouted down for relying too much on gut instinct as in her decision to trust bitcoin boys William (Ardhito Pramono) and Oscar (Chicco Kurniawan) only for them to immediately run away hoping to find the gang’s hideout for themselves after being disturbed by a strange message from the gang branding them as their allies.

Bitcoin seems like a strange thing for the revolutionaries to pin their hopes on, though it later seems they hope to do away “money” in its entirety, though it’s true enough that all of them have suffered because of the evils of contemporary capitalism. Many were victims of the same pyramid scheme, one man losing everything after his mother invested the family fortune and died soon after, and another scarred by the suicide of his wife and later death of his child. You can’t say that they don’t have a point when the press the authorities on their failure to protect the poor along with their uncomfortable cosiness with wealth and power. As their leader says, people starve to death every day because of poverty or die earlier than they would have because of a lack of access to healthcare yet the authorities don’t seem to be doing much at all to combat those sorts of “crimes”.

Nevertheless, there’s tension in the group with some opposing leader Arok’s (Rio Dewanto) increasingly cavalier attitude to human life and worrying tendency to suddenly change their well designed plans. The battle is essentially on two fronts, the police stalking them with traditional firepower and Arok fighting back with technology, harnessing the power of the internet to disguise his location while hacking police systems and public broadcasting alike to propagate his message of resistance against corrupt capitalism and oppressive poverty. Counter Terrorism does not appear to be very well equipped to deal with his new threat, but can seemingly call on vast reserves of armed troops even if in the end it’s mostly down to maverick officer Karin to raid the villains’ base largely on her own trying to rescue the boys after realising they are trying to help her after all.

These action sequences are dynamic and extremely well choreographed even if some of the narrative progressions lean towards the predictable and the final gambit somewhat far fetched in its implications. Then again, it’s also surprising that Counter Terrorism doesn’t seem to have much security and should perhaps have considered paying a little more for bulletproof glass in the control room. The subversive irony of the seeing the words “New Hope” and “deactivated” on the final screens cannot be overstated even as a kind of order is eventually restored in an otherwise unjust city.

13 Bombs screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)