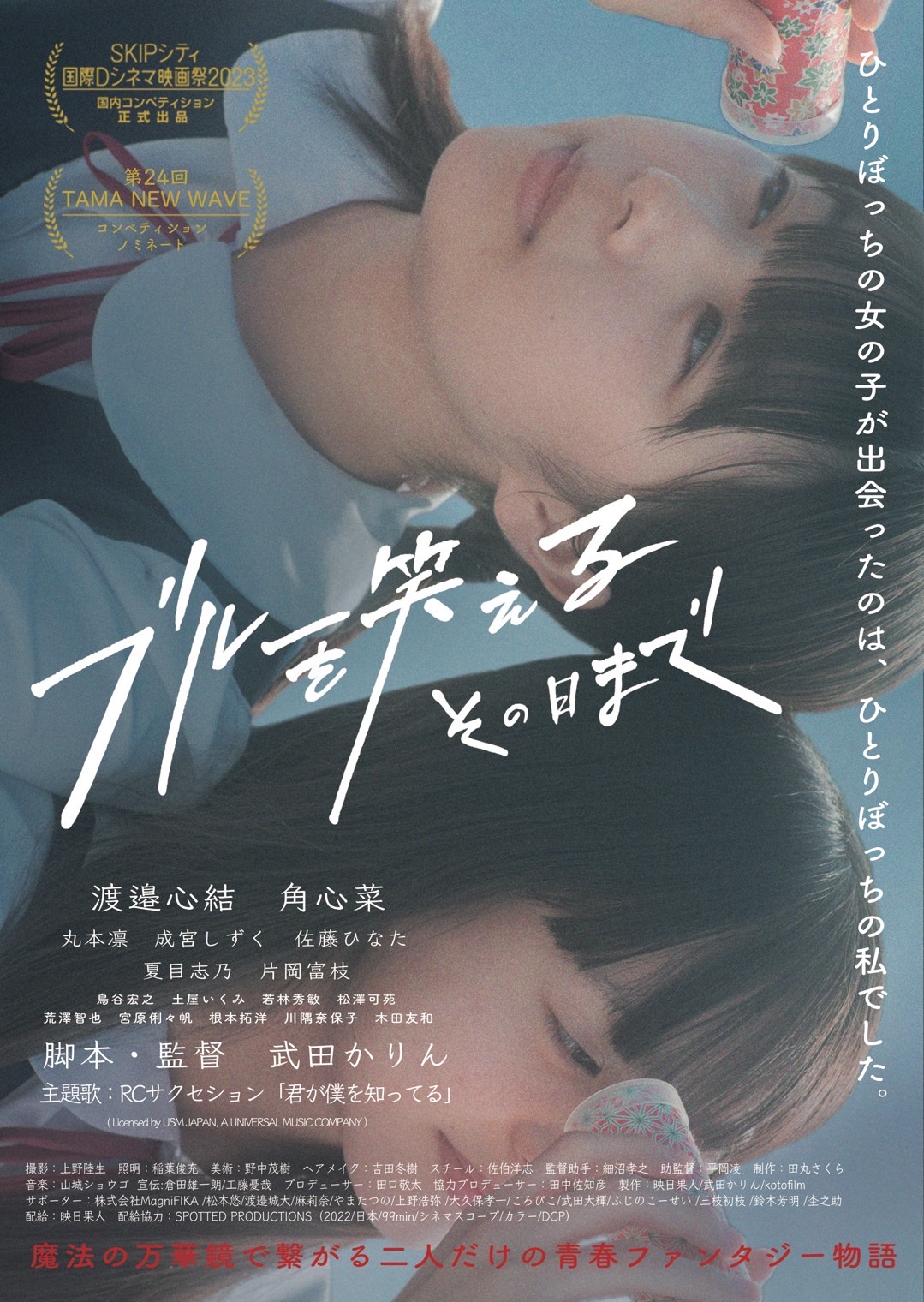

A lonely, isolated young woman finds refuge in a new friendship only to worry it won’t survive summer’s end in Karin Takeda’s gentle adolescent drama, Till the Day I can Laugh About My Blues (ブルーを笑えるその日まで, Blue Wo Waraeru Sono Hi Made). Opening with a title card reading “to you and me back in the days,” the film has an autobiographical sensibility and boundless empathy for the kids who feel they don’t fit in, that no one notices them, and their lives will never we worth living.

You can tell that Ayako (Miyu Watanabe) is depressed by her opening dialogue, “I don’t like this weather,” said to perfectly blue skies. She says everything in her life is blue, and is so shy that she literally can’t speak. Her class are reading Night on the Galactic Railroad, and though she spends the entire time reading the line that she’s figured out is hers is put off when another student heckles her because of her quiet voice and just stands there gripping the paper while her teacher prompts her with the previous line. He then just moves on to the next student, but more out exasperation than empathy, doing nothing much else to help her.

It’s not clear if Ayako was always this way or if something led to her becoming withdrawn but the other kids evidently regard her as weird while her former best friend Yuri (Rin Marumoto) has joined up with two popular girls who appear to be bullying her. Ayoko’s parents aren’t much help either, unfairly comparing her to her sister who wants to be a doctor all of which only makes Ayako feel even more useless and inadequate. It’s only when a mysterious old lady gifts her a kaleidoscope that Ayako’s outlook starts to improve and she befriends a another young girl she meets on the rooftop of the school who has a kaleidoscope too.

In discussing the passage of Night on the Galactic Railroad, which is about a friendship between two boys which ends abruptly in tragedy, a teacher asks what the milky way is made of before explaining that if you look at it through a microscope it’s full of tiny stars. Ayako too begins to see tiny stars while looking through the kaleidoscope, refracting her world and beginning to see the beauty of the light between the trees even if she’s cautioned that the patterns are pretty because you never see the same one twice. In any case, Ayako finds a kindred spirit in Aina (Sumi Kokona) but also suspects she may actually be the ghost of a girl who took her own life by jumping off the roof of the school, so their friendship can’t last past the start of the new term.

Like Giovanni in the story, Ayako has to figure out how to go on alone not just without Aina but in her complicated relationship with Yuri too who tells her she doesn’t like and hanging out with mean girls Natsumi and Nao but still joins in when they make fun of her. Some gentle words from a librarian who knows what’s she going through all too well remind her of the point of the story, that the boys still go on travelling together as Campanella still exists in Giovanni’s heart. But before all that she still ponders blowing it all to hell, saving the school goldfish but otherwise letting the place burn while wondering if she’ll ever be able to grow up.

Shot with an etherial whimsicality, Takeda shoots Ayako’s world in shades of loneliness in which her literal inability to speak is almost a reaction to the fact no one listens. Pondering the fate of a goldfish that died because of another student’s neglect she laments that no one’s kind to you until die, a comment that later seems ironic but echoes her sense of alienation. She thinks her friendship with Aina is like a dream, but like she says not necessarily one they need to wake up from because whichever way you look at it their friendship is “real”, saving each of them and giving them strength to survive until the day they can laugh about their blues smiling at a memory rather than feeling sad and alone while looking for the tiny stars hidden in the fabric of the universe.

Till the Day I Can Laugh about My Blues screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (no subtitles)