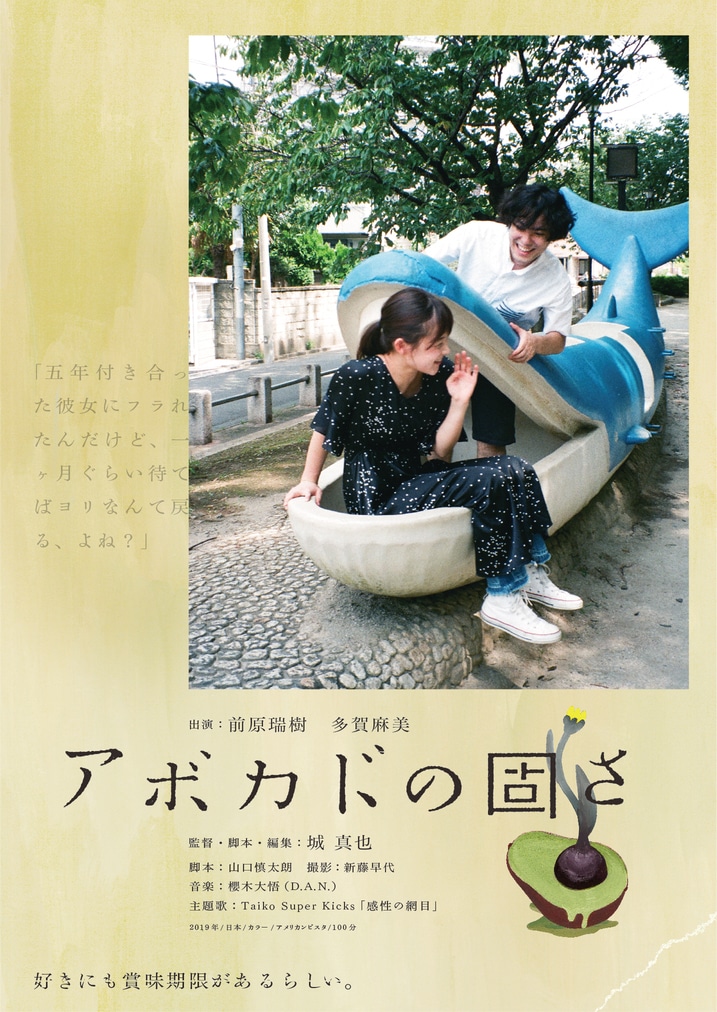

“Reality might be bitter, but at least your coffee is sweet” according to the “gloomy” voiceover performed by aspiring actor Mizuki Maehara in Masaya Jo’s The Hardness of Avocado (アボカドの固さ, Avocado no Katasa). In many ways a tale of quarter-life inertia and youthful denial, Jo’s indie drama finds its struggling hero looking for the sweet spot, trying to grab the avocado at the opportune moment between rock hard and squishy mess but floundering in world which seems both continually confusing and perhaps inherently unfair.

At 24, Mizuki (Mizuki Maehara) is a jobbing actor living with his sister (Zuru Onodera) in a small apartment. He’s been in a committed relationship with Shimi (Asami Taga) for the last five years and is already thinking about moving in together, asking her to help him pick out a sofa-bed after their date to the movies where she fell asleep and he ended up meeting a fan who recognised him from a previous film. Shimi, however, seems irritated, eventually answering Mizuki’s well meaning question about what she’d most like to do right now with the answer “break up”. In a pattern which will be repeated, Mizuki reacts somewhat petulantly, walking off with a “fine then” only to end up regretting it later. Unable to accept that Shimi is really ready to move on, he decides to give her (and himself) one month before, he assumes, they’ll get back together having each grown as people during their time apart.

This baseless optimism and mild sense of self-centred entitlement are perhaps the very things that Mizuki is supposed to be outgrowing even as he struggles to get over Shimi. Having dated for five years, Mizuki took his relationship for granted, assuming it was settled and destined to go on forever. Shimi’s declaration comes as a complete surprise, shocking in its abruptness though we can see that she seems irritated by him and that it may be more than a temporary bad mood. She tells him that she needs “freedom” and time to herself, but it seems equally likely that, from her point of view, the relationship has simply run its course. Looking through his mementos, Mizuki finds a 20th birthday card from Shimi that promised she’d always be around to encourage him, but relationships entered in adolescence rarely survive the demands of adulthood and she, it seems, is after something more while all Mizuki seems to want is more of the same.

Moping about the city, he engages in borderline misogynistic banter with his friends, occasionally irritating even them in his resentment towards a nerdy guy who has finally got a girlfriend. He finds himself applying for a job in a convenience store to make ends meet between auditions seated next to a pair of students who roll their eyes, mocking him for his lack of success as a man in his mid-20s still part-timing just like them. Meanwhile, he develops an unwise fondness for a woman he meets on a shoot, chatting her up at the afterparty but saying the quiet part out loud as he confesses his plan to have a fling while fully believing he’ll be getting back together with Shimi when the month is up. Despite the fact she has also told him she has a boyfriend, he suddenly declares his love to her, once again petulantly put out by her irritation as she points out how inappropriate he’s been seeing as all he’s done is talk about Shimi.

Shimi’s mother (Kumi Hyodo) can’t understand why she’d break up with someone as “nice” as Mizuki, and Mizuki is indeed “nice” if obviously imperfect, an earnest sort of man working hard to achieve his dreams, but she apparently wanted something less superficial, a more ”passionate and loving relationship” now that she’s outgrown adolescent romance. Mizuki is once again surprised when she brushes off his romantic overture, petulantly walking home while beginning to accept that something has indeed changed. Finally fastening the screws on his new chair (in lieu of the bed) he begins to regain some solo stability, a little more self-sufficient at least even if he still has some some growth to achieve on his own. A whimsical tale of millennial malaise and self-centred male entitlement, The Hardness of Avocado is a gentle advocation for learning to let go when something’s past its best while accepting that sometimes all you can do is set yourself right and start again.

The Hardness of Avocado screened as part of Camera Japan 2020.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

As Japan’s society ages, the lives of older people have begun to take on an added dimension. Rather than being relegated to the roles of kindly grandmas or grumpy grandpas, cinema has finally woken up to the fact that older people are still people with their own stories to tell even if they haven’t traditionally fitted established cinematic genres. Of course, some of this is down to the power of the grey pound rather than an altruistic desire for inclusive storytelling but if the runaway box office success of A Sparkle of Life (燦燦 さんさん, Sansan) is anything to go by, there may be more of these kinds of stories in the pipeline.

As Japan’s society ages, the lives of older people have begun to take on an added dimension. Rather than being relegated to the roles of kindly grandmas or grumpy grandpas, cinema has finally woken up to the fact that older people are still people with their own stories to tell even if they haven’t traditionally fitted established cinematic genres. Of course, some of this is down to the power of the grey pound rather than an altruistic desire for inclusive storytelling but if the runaway box office success of A Sparkle of Life (燦燦 さんさん, Sansan) is anything to go by, there may be more of these kinds of stories in the pipeline.