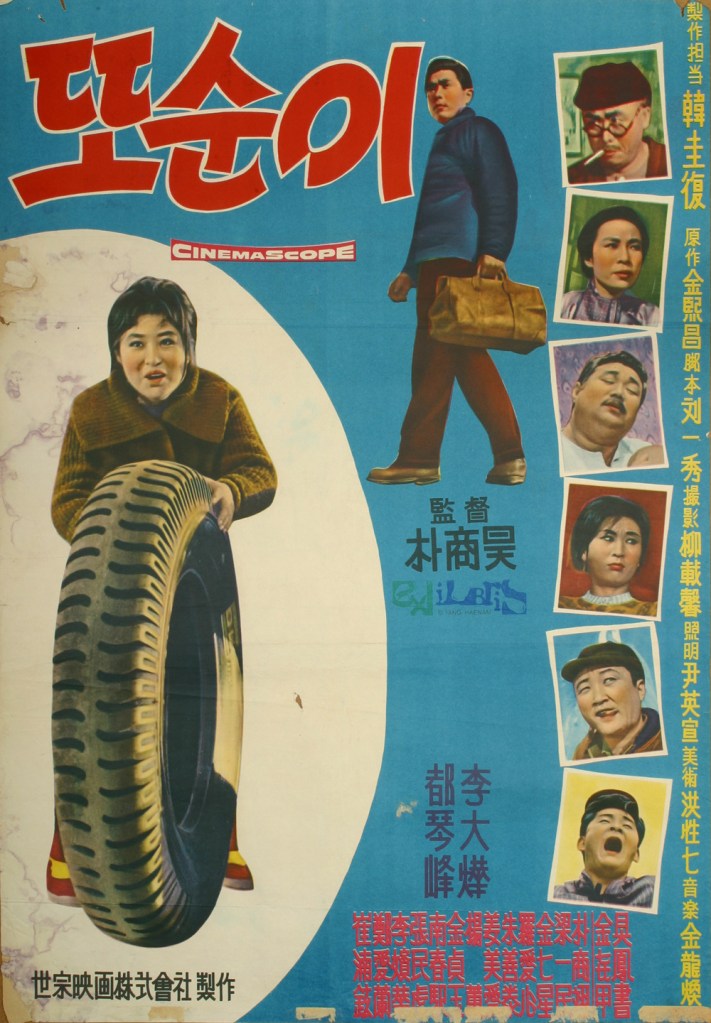

Korean Cinema had enjoyed a small window of freedom following the April Revolution that brought down the government of Rhee Syngman, but that window was closed all too soon by the Motion Picture Law brought in under Park Chung-hee which reformed the film industry and instituted an increasingly stringent censorship regime. Despite that, however, 1963 was something of a banner year which saw the release of such enduring classics as The Marines Who Never Returned, Bloodline, and Goryeojang. In comparison, Park Sang-ho’s Tosuni: The Birth of Happiness (또순이) seems like a much smaller film but was the fourth highest grossing that year, possibly because it was inspired by a hugely popular radio serial. Standing in direct contrast to contemporary melodrama, Tosuni puts a positive spin on go getting capitalistic individualism as its salt of the earth working class heroine defiantly makes her dream come true on her own despite the parade of useless men that attempt to drag her down.

The cheerful Tosun (Do Kum-bong) is the daughter of Choi Jang-dae (Choi Nam-hyeon) who came from the North with nothing but the shirt on his back and now owns a bus company. A difficult, miserly old man, Jang-dae has a loathing for people who depend on others which is why he sends a young hopeful, Jae-gu (Lee Dae-yeop), packing when he turns up with a letter of recommendation and asks for a job as a temporary driver. Unbeknowst to Jang-dae, Tosun had already encountered Jae-gu on the bus where her father had sent her on an errand only to complain she’s not come back with as much money as he hoped. Tosun asks her father for a 50 won payment for her work but he refuses, leading to a blazing row during which Tosun points out that while both her parents were out working she was basically their housekeeper so he owes her around 15 years in back pay and is also in contravention of the child labour laws. Seeing as she was looking after them all these years, she feels she’s already well acquainted with the “independence” her father always seems so keen on. Eventually she storms out, vowing to become a success on her own. Jang-dae is annoyed to have lost the argument but also oddly proud, realising that he brought Tosun up right and impressed that she actually stood up to him and can obviously take care of herself.

Tosun certainly is a very capable woman, working hard, taking every job going, and making money wherever she goes. Jae-gu, meanwhile, turns out to be something of a layabout, never really looking for a job but spending all his money drinking with the madam, Su-wol (Na Ae-sim), in a local cafe. Tosun carries on doing her own thing but also wants to help Jae-gu, not least because they pledged to try and achieve their dream of owning a modern motor car together. Jae-gu knows that Tosun is perfectly capable of getting the car on her own and is mildly put out by it, sore over wounded male pride despite her assurances that even if she’s the one who gets the money together he’s the one who’ll be driving. That’s perhaps why he’s so easily suckered by an obvious scam when he gets together with a friend who’s met a guy who needs to shift some tyres, but only after dark when there’s no one around. Tosun thinks it’s fishy, especially if they can’t take the tyres right away, but goes along with it to make Jae-gu feel better.

Like Jae-gu, most of the other young men are also selfish and feckless, dependent on and exploitative of female labour to get them out of trouble. Tosun’s brother-in-law (Yang Il-min) is forever lying to his in-laws to get loans for spurious business opportunities which never work out, complaining that he can’t “slave away as a temporary driver forever” but taking no proactive steps to change his circumstances despite the responsibilities of being a husband and father. Jae-gu’s friend, meanwhile, takes the opportunity of his wife being in hospital waiting to give birth to their child to try it on with Tosun who manages to fend him off but has a major loss of confidence because of the shock of his betrayal.

Tosun’s mother hadn’t wanted her to move out not only because that means she’s alone in the house with the difficult Jang-dae, but because being an “independent” woman was somewhat unheard of and she’s worried her daughter will lose her virtue, or at least be assumed to be a loose woman, after leaving home before marriage. Tosun might be a little naive and extremely good hearted, she keeps unwisely lending money to people who obviously aren’t going to pay her back, but as she keeps pointing out she didn’t move out for fun she wants her independence. That’s one reason she keeps Jae-gu at arms length even though she’s fallen in love with him despite her constant exasperation.

Tosun is in many ways the embodiment of a capitalistic work ethic, proving that you really can make it if you just knuckle down. The car represents both independence itself and a sense of modernity, as demonstrated by the excited commotion among Tosun’s friends and neighbours when she finally gets one and arrives to take her parents for a drive. Even the brother-in-law suddenly realises he might be better off working for Jang-dae rather than living a feckless existence of constant and humiliating failures trying to get rich quick. That’s the problem with the younger men, apparently, they want everything right away, like Jae-gu and his tyre deal, and aren’t really prepared to work at it. Tosun sorted the tyre problem in her own cooly handled fashion, outwitting the unscrupulous vendor but doing it without malice and only showing him she won’t be had. Is the motor car and everything it represents the birth of happiness? Maybe not, but it doesn’t hurt, and Tosun unlike her father seems to have retained her good heart, setting off into an admittedly consumerist but hopefully comfortable future, a back seat driver but behind her own wheel.

Tosuni: The Birth of Happiness is available on English subtitled DVD from the Korean Film Archive in a set which also includes a digital restoration before/after comparison and stills gallery plus a bilingual booklet featuring essays by Kim Jong-won (film critic & professor), and Park Yu-hee (film critic & research professor). It is also available stream online via the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.