Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story Audition adapted into a movie by Takashi Miike which itself became the cornerstone of a certain kind of cinema. However, Murakami’s output is almost as diverse as Miike’s as can be seen in his 1987 semi-autobiographical novel 69. A comic coming of age tale set in small town Japan in 1969, 69 is a forgiving, if occasionally self mocking, look back at what it was to grow up on the periphery of massive social change.

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story Audition adapted into a movie by Takashi Miike which itself became the cornerstone of a certain kind of cinema. However, Murakami’s output is almost as diverse as Miike’s as can be seen in his 1987 semi-autobiographical novel 69. A comic coming of age tale set in small town Japan in 1969, 69 is a forgiving, if occasionally self mocking, look back at what it was to grow up on the periphery of massive social change.

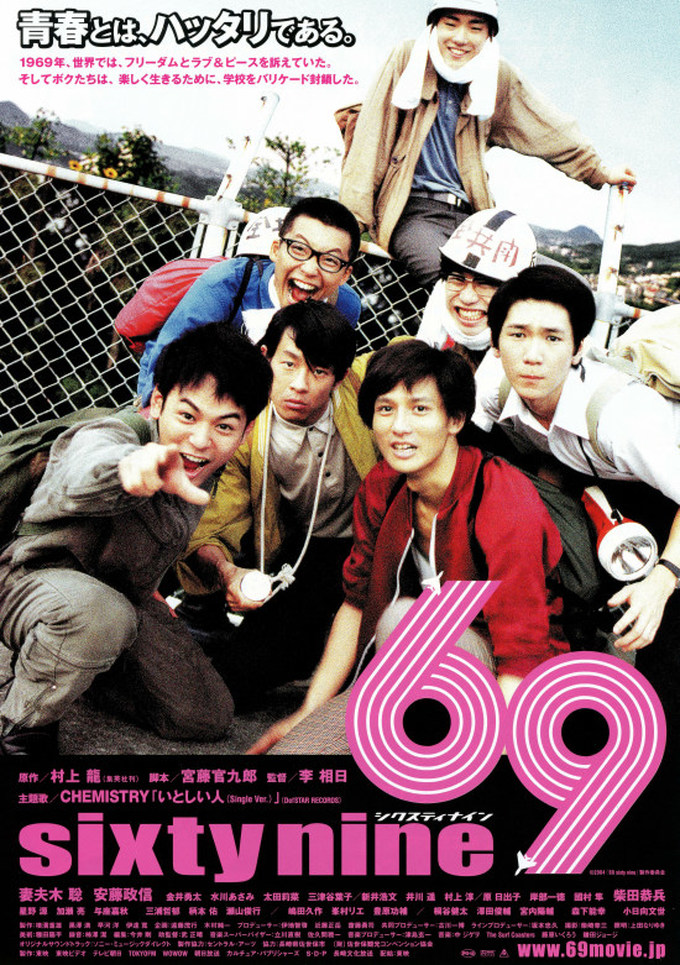

The swinging sixties may have been in full swing in other parts of the world with free love, rock and roll and revolution the buzz words of the day but if you’re 17 years old and you live in a tiny town maybe these are all just examples of exciting things that don’t have an awful lot to do with you. If there’s one thing 69 really wants you know it’s that teenage boys are always teenage boys regardless of the era and so we follow the adventures of a typical 17 year old, Ken (Satoshi Tsumabuki), whose chief interest in life is, you guessed it, girls.

Ken has amassed a little posse around himself that he likes to amuse by making up improbable fantasies about taking off to Kyoto and sleeping with super models (oddly they almost believe him). He talks a big about Godard and Rimbaud, posturing as an intellectual, but all he’s trying to do is seem “cool”. He likes rock music (but maybe only because it’s “cool” to like rock music) and becomes obsessed with the idea of starting his own Woodstock in their tiny town but mostly only because girls get wild on drugs and take their tops off at festivals! When the object of his affection states she likes rebellious guys like the student protestors in Tokyo, Ken gets the idea of barricading the school and painting incomprehensible, vaguely leftist jargon all over the walls as a way of getting her attention (and a degree of kudos for himself).

69 is a teen coming of age comedy in the classic mould but it would almost be a mistake to read it as a period piece. Neither director Lee Sang-il nor any of the creative team are children of the ‘60s so they don’t have any of the nostalgic longing for an innocent period of youth such as perhaps Murakami had when writing the novel (Murakami himself was born in 1952). The “hero”, Ken, is a posturing buffoon in the way that many teenage boys are, but the fact that he’s so openly cynical and honest about his motivations makes him a little more likeable. Ken’s “political action” is merely a means of youthful rebellion intended to boost his own profile and provide some diversion at this relatively uninteresting period of his life before the serious business of getting into university begins and then the arduous yet dell path towards a successful adulthood.

His more intellectual, bookish and handsome buddy Adama (Masanobu Ando) does undergo something of a political awakening after the boys are suspended from school and he holes up at home reading all kinds of serious literature but even this seems like it might be more a kind of stir crazy madness than a general desire to enact the revolution at a tiny high school in the middle of nowhere. Ken’s artist father seems oddly proud of his son’s actions, as if they were part of a larger performance art project rather than the idiotic, lust driven antics of a teenage boy but even if the kids pay lip service to opposing the war in Vietnam which they see on the news every night, it’s clear they don’t really care as much as about opposing a war as they do about being seen to have the “cool” opinion of the day.

Lee takes the period out of the equation a little giving it much less weight than in Murakami’s source novel which is very much about growing up in the wake of a countercultural movement that is actually happening far away from you (and consequently seems much more interesting and sophisticated). Were it not for the absence of mobile phones and a slightly more innocent atmosphere these could easily have been the teenagers of 2003 when the film was made. This isn’t to criticise 69 for a lack of aesthetic but to point out that whereas Murakami’s novel was necessarily backward looking, Lee’s film has half an eye on the future.

Indeed, there’s far less music than one would expect in the soundtrack which includes a few late ‘60s rock songs but none of the folk/protest music that the characters talk about. At one point Ken talks about Simon & Garfunkel with his crush Matsui (Rina Ohta) who reveals her love for the song At the Zoo so Ken claims to have all of the folk duo’s records and agrees to lend them to her though his immediately asking to borrow money from his parents to buy a record suggests he was just pretending to be into a band his girl likes. Here the music is just something which exists to be cool or uncool rather than an active barrier between youth and age or a talisman of a school of thought.

Lee’s emphasis is firmly with the young guys and their late adolescence growth period, even if it seems as if there’s been little progress by the end of the film. There’s no real focus on their conflict with the older generation and the movie doesn’t even try to envisage the similar transformation among the girls outside of the way the boys see them which is necessarily immature. That said, the film is trying to cast a winking, wry look back at youth in all its eager to please insincerity. It’s all so knowingly silly, posturing to enact a revolution even though there’s really no need for one in this perfectly pleasant if slightly dull backwater town. They’ll look back on all this and laugh one day that they could have cared so much about about being cool because they didn’t know who they were, and we can look back with them, and laugh at ourselves too.

Ryu Murakami’s original novel is currently available in the UK from Pushkin Press translated by Ralph McCarthy and was previously published in the US in the same translation by Kodansha USA (but seems to be out of print).

Unsubtitled trailer:

and just because I love it, Simon & Garfunkel At the Zoo