As the Japanese cinema industry continued to decline in the face of competition from television, there was perhaps paradoxically more space available for small-scale genre films. Shinichi Chiba had ushered in a new age of unarmed combat with his Bodyguard Kiba karate movies. The Street Fighter series followed hot on its heels and was enough of a hit for the studio to take notice. They suggested a new spin-off line that would feature a female action star with Chiba appearing in a supporting role and so Sister Street Fighter (女必殺拳, Onna hissatsu ken) was born.

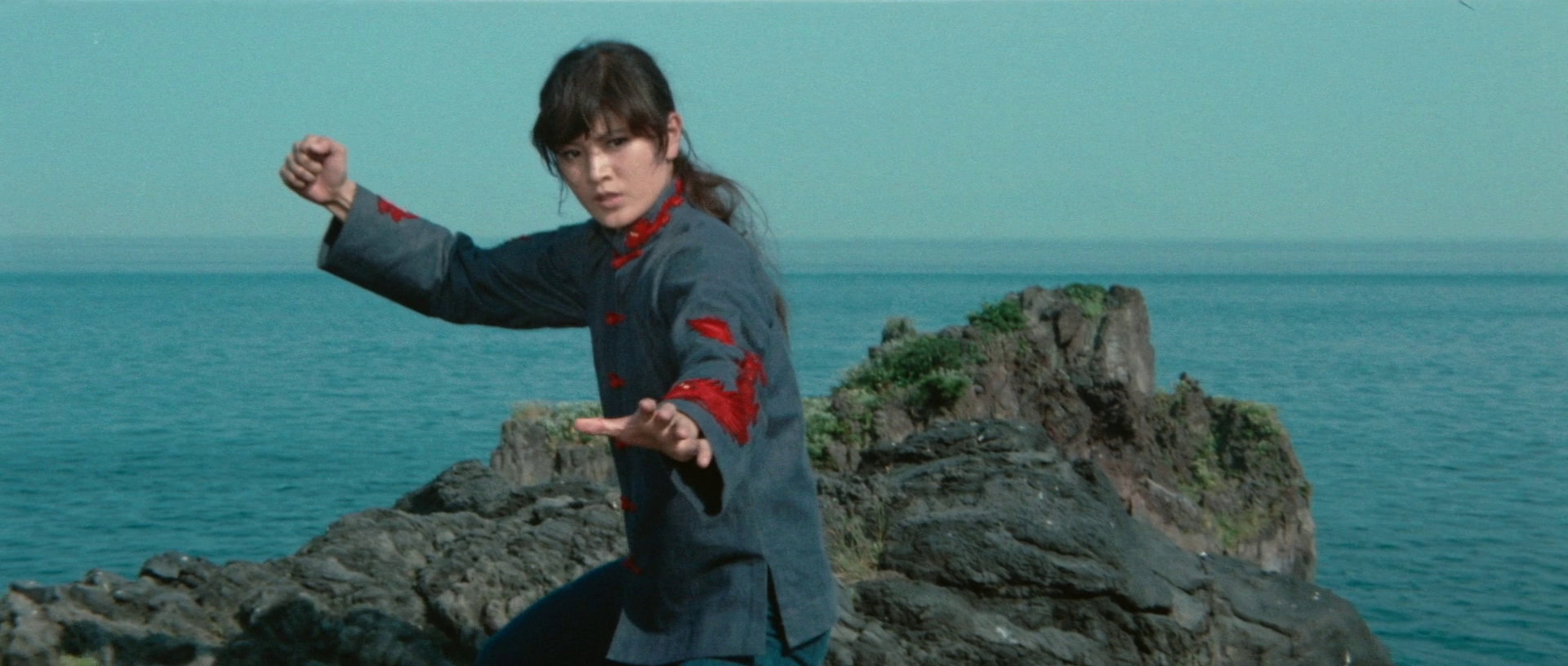

Producers apparently first wanted Taiwanese-born Hong Kong actress Angela Mao who had starred with Bruce Lee in Enter the Dragon by which the film is clearly influenced. Angela Mao was, however, unavailable, which is what led them to take a chance on Chiba’s then 18-year-old protégé Etsuko Shihomi. Shihomi had joined his Japan Action Club out of high school to study stunts, martial arts, and gymnastics and had only limited acting experience but soon proved up to the challenge of carrying a movie as a female action lead.

Koryu is the sister of a martial arts champion who has gone missing in Japan. She then finds out from his boss that he was actually an undercover narcotics agent trying to break a Japanese drug ring. As Koryu’s mother was Japanese and she still has family in Yokohama, the police inspector thinks she’d be a perfect fit to head out there, find out what’s happened to her brother Mansei (Hiroshi Miyauchi), and maybe take out the drug dealers too.

In some ways, it’s an interesting subversion of the Sinophobia often found in Japanese films of this era that this time it’s a half-Chinese woman squaring off against Japanese drug dealers. Her brother was apparently so upset about not being able to stop the drugs flooding Japan that he decided to do something reckless that directly led to his disappearance. The Hong Kong police also have a second operative, a woman, working inside the gang but have lost contact with her. In contrast to Koryu, Fang Shing (Xie Xiu-rong) has been sent in as a classic honey trap to use her femininity as a weapon by becoming the boss’ mistress to get the lowdown on the gang. But as a consequence, Fang Shing has also become addicted to drugs which the boss uses as a means to control her.

Koryu, by contrast, immediately stands up against male patriarchal control by beating up a bunch of guys that were trying to hassle her in a bar. Nevertheless, Mansei’s martial arts master says that her brother was hoping she’d get married and have a “normal life”, which does seem like quite a chauvinistic thing to say and especially to the martial arts-obsessed Koryu. Even so, he introduces her to another young woman, Emi, who got into Shorinji Kempo when Mansei saved her from being raped. These skills do after all give them the means to defend themselves against an often hostile and violent society along with granting them a greater independence than they might otherwise have.

Still, there are a selection of strange villains on show with death by blowgun and ex-priests along with the Amazon Seven team of Thai kickboxers and “Eva Parrish”, apparently the karate champion of the Southern Hemisphere. The action is quite obviously influenced by Hong Kong kung fu films and most particularly Enter the Dragon, though to a lesser extent Shaw Brothers in the warring schools subplot that sees the Shorinji Kempo love is power philosophy challenged by the gang’s very own martial artist, who feels he must wipe them out to overcome his humiliation in being defeated. Nevertheless, Koryu effortlessly takes out the bad guys as she battles her way towards saving her brother, whom the gang have started experimenting on in an effort to acquire more complex data about tolerance and safe levels for consumption of drugs. The bad guys have a full on lab in their basement where they’ve come up with an innovative solution to the smuggling issue by using wigs! It’s all quite surreal and cartoonish even when it starts getting grim, but rest assured Koryu is here to sort it all out, and sort it out she will.

Original trailer (English subtitles)