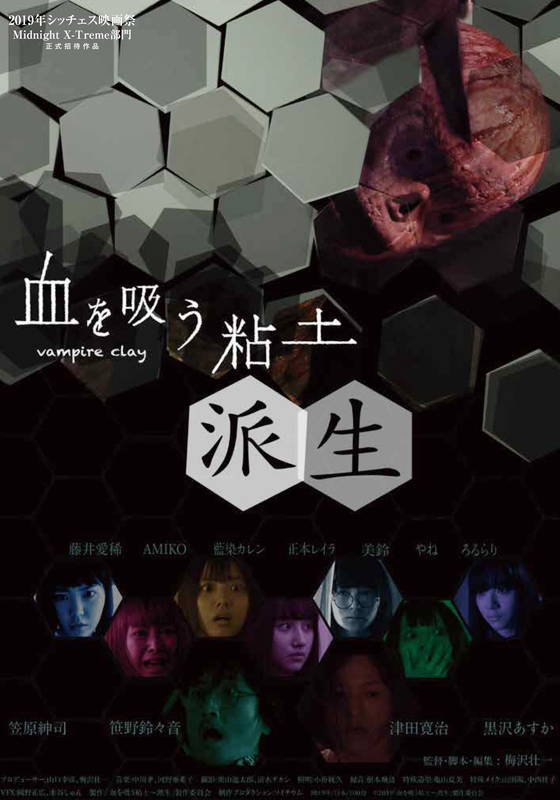

Kakame returns! Having been encased in concrete at the end of the previous film, it was perhaps inevitable that he would eventually break free to feed on the frustrated dreams of insecure artists everywhere. Kakame – Vampire Clay Derivation (血を吸う粘土~派生, Chi wo Su Nendo: Hasei) picks up shortly after the first film left off, but this time around the insecurities are less artistic than they are familial and social as those affected by the curse of Kakame find themselves wrestling with a sense of responsibility they must face alone to ensure that his bloody vengeance is contained lest he wreak more havoc on the wider world.

After a short flashback, Aina (Asuka Kurosawa) sends the surviving student home and insists on going to the police alone but is involved in a car accident. Meanwhile, we’re introduced to the new heroine, Karin (Itsuki Fujii), the daughter of Fushimi (Kanji Tsuda) who fell victim to Kakame at the end of the previous film. His body has now been found in the art school and so the police contact Karin, who is his only living relative seeing as Karin’s mother committed suicide shortly after the marriage broke down, to identity him despite the fact they had been estranged for the last 12 years. The problem is that Karin didn’t want anything to do with her dad and so she is a bit lax dealing with his bones which still contain traces of Kakame. Meanwhile, as an aspiring artist herself, she enrols in a dodgy art project run by sleazy artist Kida (Shinji Kasahara) who makes a point of recruiting six young women in their 20s because he apparently wants to know what the women of Japan today are thinking, instructing them to unbalance the unbalanceable by disrupting the harmony of the hexagonal form.

The strange apianism of the hexagonal theme is never developed further save a rerun of the events from the first film with the minor difference that is already “unbalanced” in the additional presence of Kida’s troubled assistant and the fact that he is the only male. Nevertheless, difficulties quickly arise among the girls and not least between Karin and her adoptive sister, also an artist though insecure in her abilities. Once again these tiny cracks between people are enough to let the murderous clay in, targeting first the melancholy assistant demeaned by her dismissive boss who refuses to let her participate in the project because the other girls are all students where as she is an aspiring ceramicist. Meanwhile, another suspect is provided in a young woman strangely fascinated with the bones of dead animals while Karin realises she is still in possession of one of her father’s lost in a tussle with her sister. It’s bone then, rather than blood, which condemns her but still she finds herself paying for her father’s sin in receiving a visit from Kakame as he makes swift work of the innocent artists.

The sculptor’s curse refuses to die, the other Kakame apparently fusing with a worm and creating ructions underground which threaten to destabilise the world at large. As Aina had in the first film, venal artist Kida ponders using the clay for his own ends, ironically desiring to turn it into art, perhaps making good on the sculptor’s unfulfilled desires but also exposing his own less worthy goals of becoming rich and famous which is perhaps one reason why he’s busily exploiting six pretty young women rather than getting on with his work. Aina eventually reconsidered, but then finds herself facing a similar dilemma, targeted by the police who obviously don’t buy her story about demonically possessed clay turning murderous, while wondering if it might not be better to just dump the remaining powder in the river and be done with it. Maintaining his focus on practical effects, Umezawa shifts focus slightly heading into a different register of body horror as the strange clay worms work their way into the bones of our heroes before Kakame makes himself whole, but otherwise pulls back from large scale effects often switching to blackout and soundscape as in the opening car crash. Nevertheless, what we’re left with is a tale of shared responsibility as two women of different generations refuse to let the other carry the burden alone though neither of them is in any way responsible for the curse of Kakame save for the darker emotions which helped to birth him of which we all are guilty.

Kakame – Vampire Clay Derivation screened as part of Camera Japan 2020.

Original trailer (no subtitles)