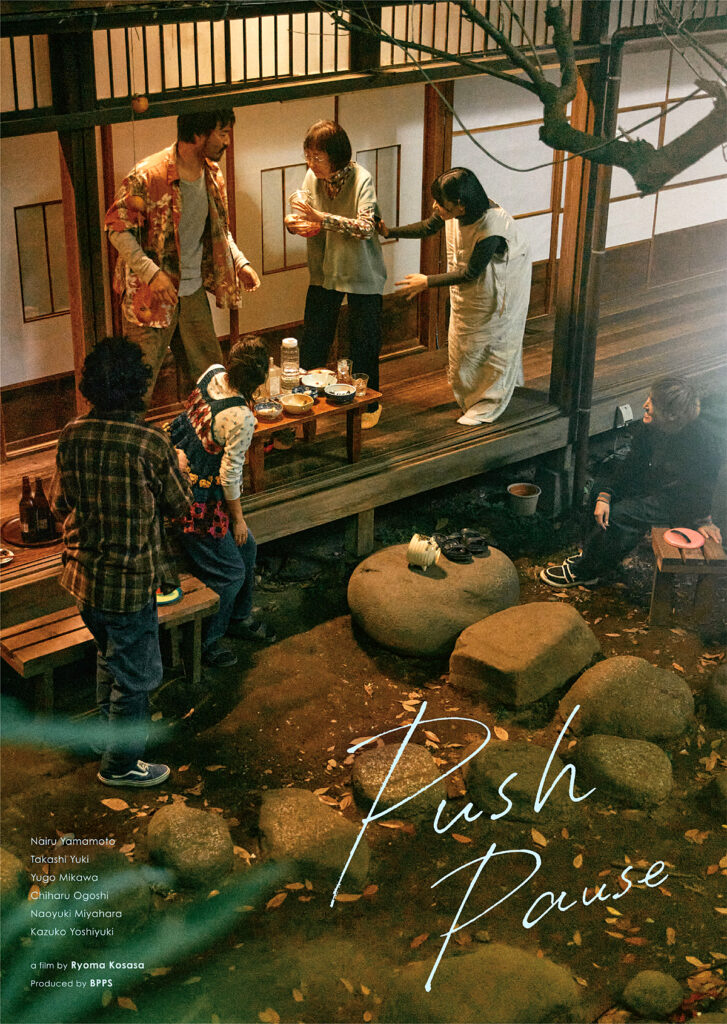

A small hotel becomes a refuge for those “struggling with the everyday” according to live-in helper Utako in Ryoma Kosasa’s heartwarming drama, Push Pause (ココでのはなし, Kokoro de no Hanashi). As she said, most of their customers are there because they’re uncertain of something and looking to take take some time out for reflection, much as she is while otherwise taking advantage of the tranquil and unjudgemental space of the inn along with the comfort it offers.

Guest House Coco is however suffering too amid the post-pandemic decline in custom. Th owner Hirofumi, attempts to sell his bike to pick up some extra cash only to discover it worth much less than he thought. The first of their guests, Tamotsu, is struggling for similar reasons seeing as the owner of the batting cages where he works is considering closing down as customers continue to stay away leaving him floundering for new direction. Helping an old friend move brings him into contact with someone he worked with for the Paralympics, but it only seems to fuel his sense of insecurity reflecting that unlike his friend he has no talents or ambitions and isn’t sure he wants to return to work for with him because it only makes him feel bad.

For Xiaolu, meanwhile, she’s dealing with issues as of a different order while house hunting in Tokyo ahead of a job transfer. Though her colleague had agreed to help her, he suddenly tells her he’d rather she didn’t come mostly it seems because he’s afraid she’ll expose him as an otaku thanks to their shared love of anime and people in the office will make fun of him. But then he also drops in that most of his colleagues are subtly racist, even insensitively adding that Xiaolu doesn’t “look Chinese” on first glance especially as her Japanese is so good unwittingly exposing his own latent prejudice. Her parents in China keep calling her to come home especially as her grandmother is in poor health leaving Xiaolu feeling guilty and now slightly unwanted unsure if it’s a good idea to accept the transfer or even remain in Japan at all.

Even Izumi, a permanet resident of the guest house, accidentally hurts her feelings in innocently asking if she’s from China on hearing her name though as it turns out Izumi was herself born in Manchuria and apparently a war orphan though in truth she seems nowhere near old enough to have been born in the 1940s. In any case, Izumi is the beating heart of Coco providing the warm and homely environment that sets people at their ease and makes them feel welcome and accepted. As she tells Xiaolu, fate has a way of bringing people together or at least getting them where they need to be so they can make an informed choice about their futures.

That’s why she echoes the title of the film in giving some advice to the young from a position of age in telling them that it’s alright to slow down, take a few moments to think things through rather than feeling as if they need to charge ahead. According to her, youth is just a part of your life that doesn’t even last very long so there’s no need to rush through it which seems like valuable advice to near middle-aged inn owner Hirofumi who is considering proposing to his girlfriend but is uncertain because she has children already and he isn’t sure they’ll accept him. Utako too has her own problems she’s in part been hiding from in leaving her home town to hole up in the inn.

As if bearing out the sense of community that arises at there, Utako reveals that they stay in contact with their guests giving them the sense of a secure place to return to where they’ll always be accepted and cared for. Thanks to the support of the others at the Coco, each of them begin to find new directions in their lives and are able to proceed with more confidence and certainty. Warmhearted and empathetic Kosasa’s gentle drama is and ode to the quiet solidarity and unexpected connections that arise between people each struggling with the everyday but finding new strength in each other.