Hiroshi Shimizu is often remembered for his talent as a director of children, something which he brings to the fore with his melancholy meditation on the immediate post-war world in Children of the Beehive (蜂の巣の子供たち, Hachi no Su no Kodmotachi). This is a destroyed society, but one trying to make the best of things, surviving in any way possible. It’s fairly clear from Shimizu’s pre-war work that he did not entirely approve of the way his country was heading. Children of the Beehive seeks not to apportion blame, but merely to make plain that no one can get along alone here, in the post-war world there are only orphans and ruined cities but that itself is an opportunity to rebuild better and kinder than before.

Hiroshi Shimizu is often remembered for his talent as a director of children, something which he brings to the fore with his melancholy meditation on the immediate post-war world in Children of the Beehive (蜂の巣の子供たち, Hachi no Su no Kodmotachi). This is a destroyed society, but one trying to make the best of things, surviving in any way possible. It’s fairly clear from Shimizu’s pre-war work that he did not entirely approve of the way his country was heading. Children of the Beehive seeks not to apportion blame, but merely to make plain that no one can get along alone here, in the post-war world there are only orphans and ruined cities but that itself is an opportunity to rebuild better and kinder than before.

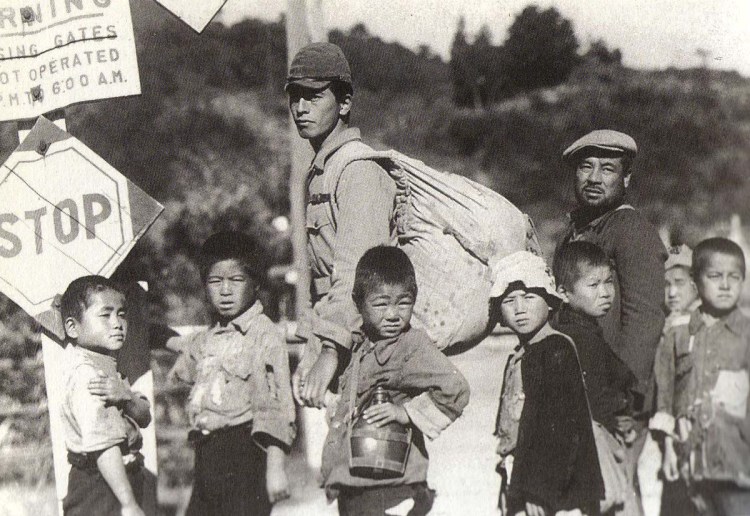

The scene begins with a few street urchin kids plying their trade by pickpocketing at a railway station. A bewildered soldier lingers on the platform, uncertain of what to do next but decides not to board a train after all. Like these children, he himself is an orphan and has no real place to go back to, no family waiting to greet him. The children work for a Fagin-like street thief with one leg and no scruples who has them doing all sorts of not quite legit enterprises but after all he’s just trying to survive too. Outside, the gang run into another lady who’s been trying to get a telegram through to a distant friend but isn’t having much luck. Eventually the soldier decides to travel with the boys, leading them to the only place he has left to think of as “home”, an orphanage far out in the country.

Like many of Shimizu’s films, Children of the Beehive adopts a loose road trip format as he takes us along bumpy narrow roads and mountain passes. Occasionally we hit the cities though in a matter of fact way. Hiroshima crosses our eyes as a vista of devastation, a crater where a city used to be though this is just how it is there, no sadness or repudiation, just a resignation to the way the world now looks. The children rough and tumble their way through, quickly taking to the new “paternal” figure of the kindly soldier who, despite the obvious hardships he must have faced himself, is determined to teach them to be softer in a world which only wants to make them hard.

A poignant moment occurs when the children come across a school and one of them sits underneath an open window, wishing he could go to class like the other kids. The soldier doesn’t have much education himself but also laments that boys aren’t in school. At least one of them can read and write (to the level appropriate for his age) so presumably they received some kind of education during the war but have obviously not been receiving any tuition since being orphaned. The soldier does what he can but his lessons are generally more of the life variety as he teaches the children the importance of honest labour, working together and treating others with respect. When the children encounter another group of boys who run away from them, one boy gets upset and calls them “mean” but the soldier explains that it’s not their fault, they’re just afraid so the boys need to be extra nice to show them there’s no need to feel scared.

Similarly, when they meet other orphaned street kids who seem to be nervously hanging around, partly afraid but also wanting to make contact with a large group of other children, the soldier allows them to join the gang (so long as they’re prepared to earn their keep and work alongside everyone else). There is sadness here, and darkness lurking around the edges but Shimizu refuses to judge. The soldier accepts everyone as they are but tries to teach them by example. When the ragtag bag of displaced persons finally reaches its destination no one is left behind. Everyone is invited into this new family built out of the ruins of a defeated society.

Shimizu made good on his progressive ideals. The kids in the movie aren’t actors but actual war orphans whom Shimizu did indeed take in and educate later even going so far as to open an orphanage. Shimizu believes in the essential goodness of ordinary people and that small gestures of personal kindness elevate the world around them, provoking kindness in others and ultimately making the world a more bearable place even if they create no great social change. When the group finally arrives at the children’s home, the boys’ (and they do all seem to be boys, no word on what happens to female war orphans) voices throng like a swarm of busy bees, an apt metaphor because this is a place of intense industry where gentle flowers are pollinated with the simple power of love in the hope of growing a better, kinder society built on mutual support and acceptance.

Another great Shimizu film that I see (there were 5 in a week). Why is he so overlooked in the West? This film reminded me a lot of Italian neo-realist cinema, especially Rossellini’s “Germany, Year Zero” (with the huge difference of having a more positive and hopeful ending).

(BTW: Your blog has already become a reference for me. Wonderful job.)

Thank you Alexandre, that is so great to hear. Hopefully one day Shimizu will get the recognition he deserves!

I use this post to ask about another Japanese film: have you seen “Bitterness of Youth” by Tatsumi Kumashiro, 1974? I was surprised not to find a blog entry of yours about the film, which I found quite interesting.

I actually haven’t. I’ll be sure to check it out, thank you!