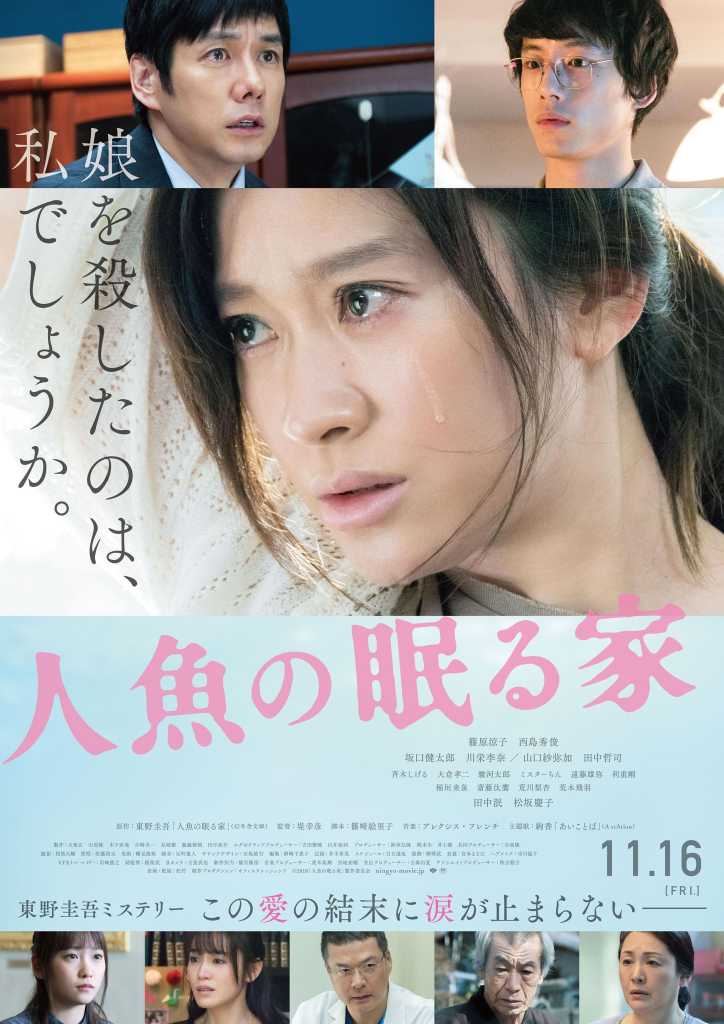

In most countries, the legal and medical definitions of death centre on activity in the brain. In Japan, however, death is only said to have occurred once the heart stops beating. The bereaved parents at the centre of The House Where the Mermaid Sleeps (人魚の眠る家, Ningyo no Nemuru Ie), adapted from the novel by Keigo Higashino, are presented with the most terrible of choices. They must accept that their daughter, Mizuho, will not recover, but are asked to decide whether she is declared brain dead now so that her organs can be used for transplantation, or wait for her heart to stop beating in a few months’ time at most. As their daughter was only six years old, they’d never discussed anything like this with her but come to the conclusion that she’d want to help other children if she could. Only when they come to say goodbye, Mizuho grasps her mother’s hand giving her possibly false hope that the doctor’s assurances that she is brain dead and will never wake up are mistaken.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the Harimas were in the middle of a messy divorce when they got the news that Mizuho had been involved in an accident at a swimming pool. Kazumasa (Hidetoshi Nishijima), Mizuho’s father, is the CEO of a tech firm specialising in cutting edge medical technology mostly geared towards making the lives of people with disabilities easier. He does therefore have a special interest in his daughter’s condition and is willing to explore scientific solutions where most might simply accept the doctor’s first opinion. His wife, Kaoruko, meanwhile has a deep-seated faith that her daughter is still present if asleep and will one day wake up.

It so happens that one of Kazuma’s researchers (Kentaro Sakaguchi) specialises in a new kind of technology which hopes to restore motor function through artificial nerve signals controlled by computers and electromagnetic pulses. He hatches on the idea of using the technology to improve his daughter’s quality of life by letting her “exercise” to maintain muscle strength, but despite the excellent results it achieves in terms of her health, it takes them to a dark place. Muscle training might be one thing, but having Mizuho make meaningful gestures is another. They don’t mean to, but they’re manipulating her body as if she were a puppet, even forcing her to smile without her consent.

Kazumasa starts to wonder if he’s gone too far. Seeing his daughter’s face move with no emotion behind it only proves to him that she is no longer alive. Meanwhile, he comes across another parent raising money to send his daughter to America for a life saving heart transplant and begins to feel guilty that perhaps his decision was selfish. The father of the other girl sympathises with him and confides that they can’t bring themselves to pray for a donor because they know it’s the same as praying for another child’s death, but Kazumasa can’t help feeling he’s partly responsible because he made the choice to artificially prolong his daughter’s life but now realises that she is little more than a living a doll.

This is something brought home to him by Kaoruko’s increasing desire to show their daughter off. Her decision to take her to their son Ikuo’s elementary school entrance ceremony instantly causes trouble with the other parents who feign politeness but are obviously uncomfortable while the children waste no time in ostracising Ikuo because of his “creepy” sister. Kazumasa privately wonders if Kaoruko’s devotion has turned dark, if she’s somehow begun to enjoy this new closeness with her daughter to the exclusion of all else and has lost the power of rational thought. He can’t know however that perhaps she’s coming to the same conclusion as him, but it finding it much harder to accept that they might have made a mistake and all their interventions are only causing Mizuho additional suffering.

What’s best for Mizuho, however, is something that sometimes gets forgotten in the ongoing debate about the moral choices of her parents and relatives. Kazumasa’s colleagues accuse of him of misappropriation in monopolising a key researcher, hinting again at the “selfishness” of his decision to expend so much energy on treating someone whom many believe to be without hope when there are many more in need. The researcher in turn accuses Kazumasa of “jealousy” believing that he has displaced him as an “artificial” father working closely with Kaoruko in caring for their daughter. The “life” in the balance is not so much Mizuho’s but that of the traditional family which is perhaps in a sense reborn in rediscovering the blinding love that they shared for each other which will of course never fade. What they learn is to love unselfishly, that love is sometimes letting go, but also that even in endings there is a kind of continuity in the shared gift of life and the goodness left behind even after the most unbearable of losses.

Screened as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2020.

Original trailer (English subtitles)