“You can’t steal a life and get off the hook” a sheepish young man is told by an unsympathetic police officer pushing him to confess his crime, but the “justice” he will later face will be of a less official kind. Eisuke Naito’s ironically named Forgiven Children (許された子どもたち, Yurusareta Kodomotachi) is, in some ways, a tale of sympathy for the bully in the acknowledgement that a bully can be a victim too, but it’s also a condemnation of a bullying society defined by pent up, misdirected rage in which wounded people take out their hurts for thousands of petty humiliations on those they see as in some way vulnerable in an attempt to prove that they are not.

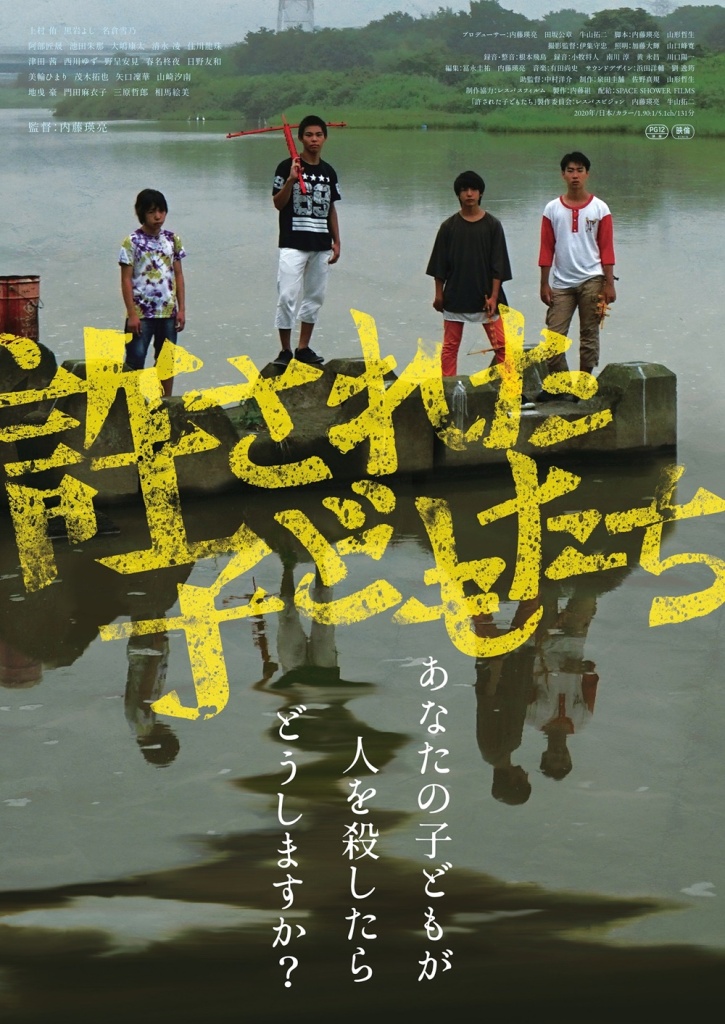

The “hero”, Kira (Yu Uemura), was mercilessly bullied in primary school. The first time we meet him he is wandering wounded, bleeding profusely while stumbling home without shoes. Some years later, now 13, Kira has a scar on his cheek and a mean look in his eye. At school he’s an angry young man and petty delinquent while at home a dutiful son cheerfully singing karaoke with his loving parents. Everything changes one day when he bullies another boy into bringing a homemade crossbow to the riverbank. Without really knowing why, Kira fires it and pierces him through the neck. Terrified, the other boys flee leaving Itsuki (Takuya Abe) to die alone by the water undiscovered for hours.

Kira and the others are not that smart. They’re on CCTV heading to the riverbank, and there are messages on Itsuki’s phone from Kira telling him to meet them there. It is obvious they are involved though in legal terms the evidence is circumstantial. The policeman who visits encourages Kira to confess, implying it was an accident, or risk further punishment if he says he’s innocent and is later found not to be. Kira confesses, but his overprotective mother (Yoshi Kuroiwa) convinces him to recant, hires a fancy lawyer who bullies the only one of the other boys brave enough to tell the truth into straightening his story, and gets him off but the right wing internet trolls have already gone into overdrive and guilty or not Kira will not be allowed forget his crime.

This is of course ironically another kind of bullying. The constant through-line is that Kira is the way he is because of the bullying he endured in primary school. He is a young man consumed by rage and taking revenge for being made to feel small and vulnerable by making others feel the same. After being forced to move around a few times, Kira ends up in a new school where they’re supposed to discuss how to address the bullying problem but worryingly most of the other kids have no desire to solve it. Rather than ask why people bully others, they universally blame the victims, insisting that it is their own fault simply for being the sort of people who get bullied. That might be because they are in some way different or vulnerable, but oftentimes is just a cosmic quirk of personality. Of course, bullies rarely think of themselves in those terms, which might be why one particularly vindictive young man voices the worrying principle of “justifiable bullying”, branding himself as a hero of justice as he prepares to unmask Kira as a murderer in hiding.

Kira meanwhile remains conflicted, unable to come to terms with his crime or his internalised rage. Some might feel his bullying is indeed “justifiable” because in this case he is guilty and could make some of it at least stop by engaging in dialogue with Itsuki’s parents even if he cannot expect to be forgiven and must consent to carry the burden of his crime for the rest of his life, but it does not excuse the wholesale hounding of himself and family which prevents any kind of future restitution. Why is this society so angry that people go online to issue death threats against a 13-year-old boy over a crime that has absolutely nothing to do with them, what it is that they are really so outraged about? Kira is merely a product of an inescapable spiral of misdirected rage and emotional austerity.

The children turn a blind eye to the bullying of others, or are encouraged to join in to avoid becoming victims themselves while adults claim to want to help but only contribute to the stigmatisation of those who are bullied. Kira says he thinks that he had a reason for doing what he did, but no longer remembers, later refocussing his rage on bullies to avoid having to recognise the bully in himself. But society is itself a bully, consumed by misdirected rage and a socially conservative tendency to blame and exclude rather than understand which ensures that there can be no end to the cycle of violence and abuse until society learns to look within itself.

Forgiven Children was streamed as part of this year’s online Nippon Connection Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)