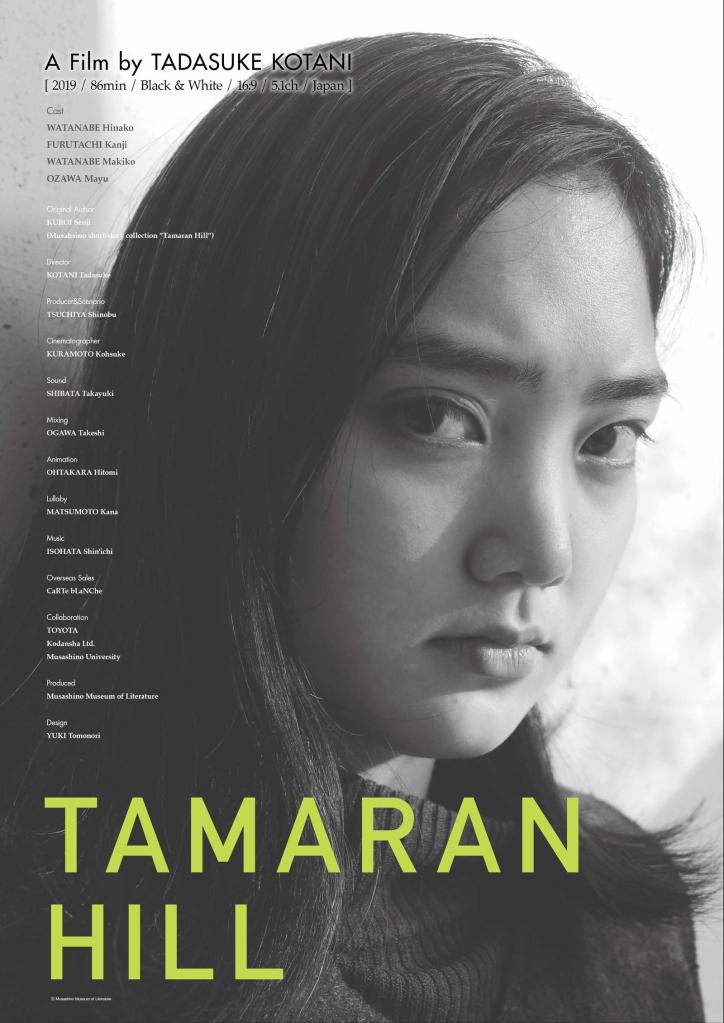

Does Japan have more uphills or downhills? You have to think about that one for a second, like one of those trick questions they put in books for children. Nevertheless, you can’t argue with the idea that so much of life is really about perspective and perhaps perspective itself can also be a subjective choice. Shot in crisp black and white with occasional animation and adapting the novel by Seiji Kuroi who actually appears at one particularly meta moment, Tadasuke Kotani’s Tamaran Hill (たまらん坂, Tamaranzaka) follows a young woman’s path towards forging, or perhaps rediscovering, her identity through a meditation on the word “unbearable”, its association with her father, and the long buried memories of a potential hometown.

Hinako (Hinako Watanabe), a college student, lost her mother at four years old and is at something of a crossroads as she contemplates her future. Her teacher (Makiko Watanabe), who for some reason has an ever present robot assistant at her side, advises Hinako and her fellow students that if they want to get a good job what they need to get good at is the art of narrative lying. They need to assert their individuality in inoffensive ways, quantify their experiences in concrete numbers, but avoid embellishing facts in which hard evidence is available. Her advice to Hinako is that she needs to create a convincing “character” to pep up the self intro on her CV, perhaps paint herself as a survivor who lost her mother not to cancer of the vocal chords but in a natural disaster.

Hoping to start at the beginning in rebuilding herself, Hinako begins researching the idea of “hometowns” only to be sidetracked by a book titled “Tamaran Hill”. The title catches her eye because “tamaran” which means “unbearable” is one of her father’s catchphrases, indeed we heard him say it numerous times after getting stuck at the airport by a typhoon meaning that he couldn’t get back for his late wife’s memorial service. In the book, the narrator details his friend’s increasing obsession with a slope near his home by the name of Tamaran Hill, something with which Hinako also becomes intrigued as she finds herself sliding into the narrative, the narrator detailing her own experiences as if she were reading them.

It seems that for most, “tamaran” does indeed mean “unbearable”. The explanations for the name run from a deserting samurai decrying the folly of war as he ran from a nearby battlefield to Showa-era students resentful at having to climb uphill to gain their education but Hinako is disappointed to learn that the answer may be far more prosaic than she’d hoped. Reality and fiction begin to blur. She finds herself asking if an old man is merely a character from her imagination only to receive a philosophical answer that characters are composed of words but that words have vitality, warmth, and power. Meanwhile she begins to have visions of a mysterious past which mingle with those of the narrator’s friend leading her towards the “hometown” she has long been looking for.

Hinako’s “unbearable” Buddhist priest father (Kanji Furutachi) apparently doesn’t like to talk about the past, which might be why she feels so lost, while he also berates her for not properly looking after her seemingly adopted younger brother. He actively hides from her the keys to her history, offhandedly remarking on the reappearance of a long absent relative in Hinako’s questions about a mysterious cosmos flower placed on her mother’s grave. Hinako wonders if it’s her mother’s fault that she can’t love anyone, retracing her steps inspired both by the novel and a letter hidden by her father in order to make sense of the brief and fragmentary memories which comprise her visions and thereby reconstruct an image of herself which is, essentially, narrative.

Hinako’s process towards self identification hints at personal fictions and the strange alchemy of fantasy and reality that is memory, but she does at least seem to have straightened her story as per her teacher’s instruction, confidently stating that she has “decided” on her hometown. Perhaps the fiction is more reliable than truth in its manufactured certainties, and after all no one takes “just be yourself’ at face value. Does the slope go up or down, or is it actually on the level and it’s just that everything else is tilted? It’s all a matter of perspective, “unbearable” only in its inscrutability.

Tamaran Hill streamed as part of this year’s online Nippon Connection Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)