“We’re just ordinary people” the heroine of Just the Two of Us (二人ノ世界, Futari no Sekai) eventually exclaims in exasperation with the often hostile world around her. Produced by Kaizo Hayashi as a project for students at the Kyoto University of the arts, Keita Fujimoto’s sometimes bleak social drama offers a less rosy view on disability in the contemporary society than has perhaps been seen in recent Japanese cinema as the twin protagonists each struggle against prejudice and preconceived notions of how disabled people should live while internalising a sense of shame and impossibility that leaves them with little hope for the future.

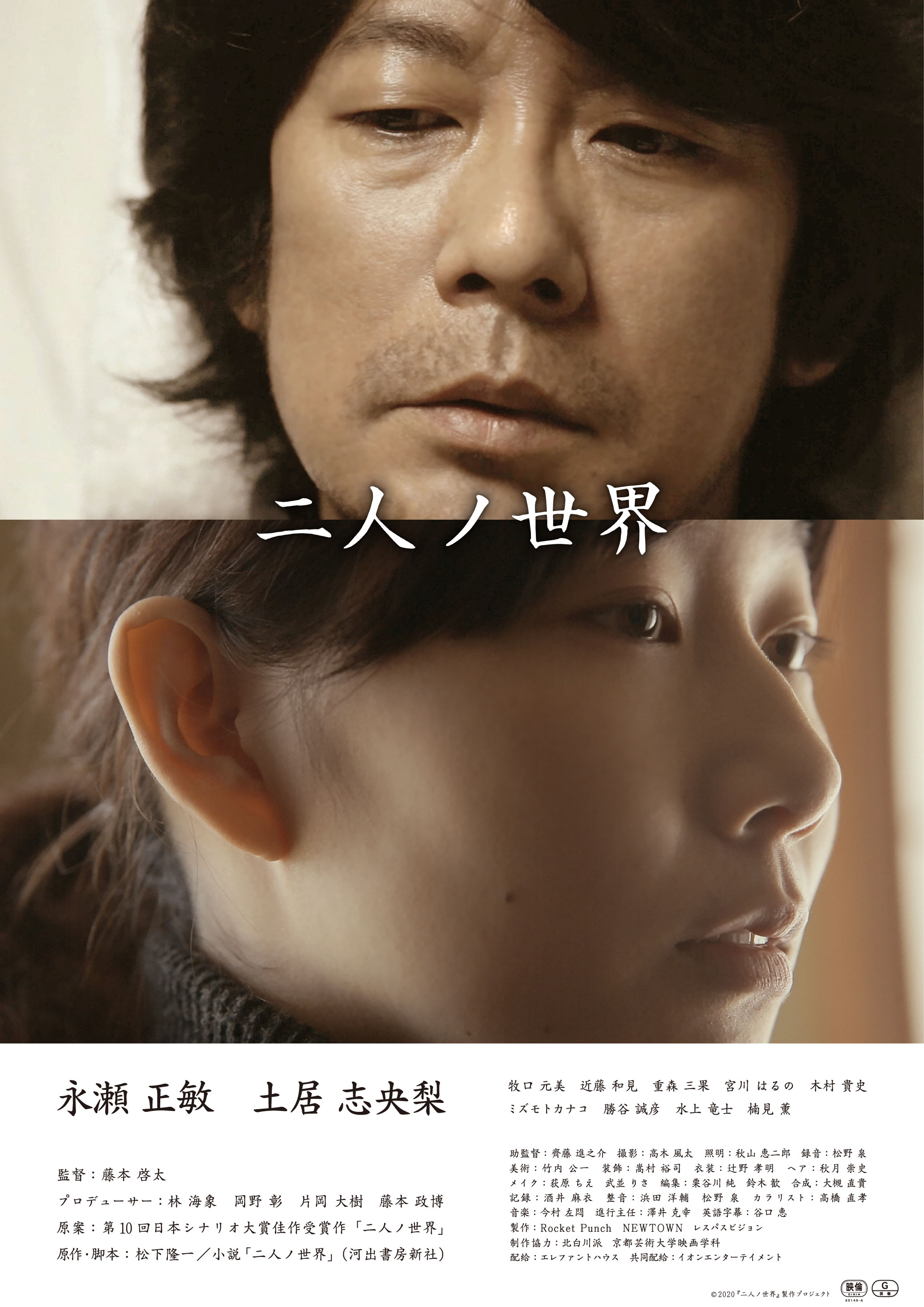

Opening in darkness, the scene then shifts to bright sun light as a young woman, Hanae (Shiori Doi), is woken by a phone call informing her she has been unsuccessful in a recent job application. Meanwhile, Gohei (Motomi Makiguchi), an old man caring for his son Shunsaku (Masatoshi Nagase) who has been paralysed from the neck down since a motorbike accident some years previously, finds his latest attempt to hire a carer ending in failure, Shunsaku deliberately making obscene comments towards the earnest young woman leaving her so upset that she leaves in tears and does not return. After hearing Gohei discussing his problem on a local radio show, Hanae decides to apply for the job the only thing being that she herself is blind which is why she’s been having so much trouble trying to find employment.

Gohei has his doubts, but after talking to the young woman and witnessing her take no notice of Shunsaku’s attempts to make her uncomfortable, he decides to take her on in part because she reminds him of his late wife and he instinctively feels that he can trust her. As we discover, that’s something all the more pressing to Gohei because not only is he finding it increasingly difficult to care for his son as he himself ages but is also suffering with a serious medical condition and worrying who will look after him once he’s gone. For all these reasons he places a heavier responsibility on Hanae than she had expected, showing her where the spare key is in case she needs to get in when he’s out and even handing over their passbooks and bank cards. A little shocked, Hanae asks him if that’s really necessary, how does he know she won’t just run off with them but he simply tells her that he knows she’s not the sort of person who would do something like that and indeed she isn’t.

As she later reveals, Hanae has no family of her own repeatedly reminding Shunsaku that he was lucky to have parents that loved and cared for him as much as they did. She becomes in a sense a member of the family, Gohei telling hospital staff she is his daughter while later even Shunsaku claims to be her husband in order to make a point. Yet the arrangement is not one that all find suitable, Shunsaku’s snooty aunts instantly taking against Hanae on the grounds that they cannot believe a blind woman could care for a paralysed man while simultaneously attempting to chase Shunsaku out of his home he fears disguising their desire to get their hands on the inheritance as concern for his wellbeing. They continue to infantilise him, refusing his right to make his own decisions over his life even though he is a man in his 40s of entirely sound mind insisting he should be put away in a nursing home rather than allowed to live as independently as possible in a house which he owns.

Tellingly Shunsaku had been reluctant to leave the house afraid of the stigma and judgement he may receive from others in an ableist society, a fear later borne out by their encounter with an extremely rude man while trying to enjoy a summer a festival. Hanae who had been partially sighted since birth and lost her sight entirely five years previously reassures him that she feels people staring at her all the time but has had to become used to it in order to carry on with her life, her courage and support beginning to give him the desire to begin living again yet the world continues to place various barriers in their way eventually removing all sense of hope and possibility that the decisions they’ve made for themselves will be accepted or that they could become a conventional family supporting each other.

“How can we live without bothering others?” Hanae eventually snaps back at the snooty aunts, signalling perhaps a slightly problematic framing that leans into the idea that Hanae and Shunsaku are burdens and that their presence is never anything other than a nuisance to those around them rather than taking others to task for their refusal to accept disabled people as equals or to treat them with basic human empathy. The conclusion is further reinforced by the bittersweet ending which echoes the film’s title implying that the pair can stay together but only by accepting exile from mainstream society and retreating into a world of two. Nevertheless, Fujimoto’s often sensitive, elegantly shot drama has genuine poignancy even in its melancholy conclusion as the marginalised heroes find solace in each other in defiance of a hostile society.

Original trailer (no subtitles)