Shiori Ito, then using just her first name, made headline news when she decided to go public naming a prominent political journalist with strong ties to then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as the man who had drugged and raped her following what she believed was an appointment to discuss a potential job working overseas. Using recordings made at the time along with footage filmed more recently, Black Box Diaries is a kind of companion piece to her book Black Box which details her quest for justice in the face of a misogynistic justice system and conservative society.

The reason she’d only used her first name at her original press conference was to protect her family because there is significant social stigma attached not only to being a survivor of sexual assault but for daring to speak out and disrupt the illusion of social harmony. In fact, during the opening sequence which takes place in a long dark tunnel we hear a recorded phone call with Shiori’s sister who pleads with her not to show her face. The families of those who appear in the news often become targets for the media and can end up being ostracised by their communities or losing their jobs and livelihoods. Shiori herself also tearfully remarks on the guilt and uncertainty she feels because she knows that her decision, which she feels necessary, will have a negative impact on her friends and family while she herself continues to receive hate mail from those who call her an opportunist or ask why talks down her country while continuing to live there.

There is an essential irony in the fact that it’s Shiori who ends up in a symbolic prison, having to leave her apartment and stay with a friend unable to venture outside or work for fear of being hounded by the press. Her decision to go public was motivated by the failure to gain justice via the judicial system firstly because the police do not take her attempt to report her assault seriously. At that time (though they’ve since been updated), Japan’s rape laws hadn’t changed since the Meiji era and were rooted not in ideas of consent but only in whether or not physical violence had taken place and the victim had resisted physically. The secondary charge of “quasi-rape” was used in cases such as these when the victim was unable to do so because they had been drugged or incapacitated in some other way. Thus even though Shiori has evidence such as CCTV footage that shows her being physically carried out of the taxi into the hotel and barely able to walk, it does not help her case and nor does DNA on her bra because it only proves that her assailant touched it and nothing else. An investigator describes what happened to her as taking place within a “black box” that no one can ever really see inside.

But for all that, the film touches on the way that other people latch on to her case and try to use it for their own ends such as an offer from Yuriko Koike, the ultraconservative mayor of Tokyo, to join her new political party which she had started to challenge the ruling LDP of which she was once a member in fact serving as a cabinet minister under Shinzo Abe during his first stint as Prime Minister in 2007. The editor of her book also tells her that the reason everything’s moving so quickly is because of the upcoming election and people should have this kind of information before they vote. The Abe administration was plagued by scandal and accusations of cronyism which the suggestions that he personally intervened because Yamaguchi was a friend of his (and coincidentally also had a book coming out which was a biography of Abe) only furthered this narrative. Shiori counters that she wasn’t really interested in politics (of this kind, at least) and was just trying to tell her story in the interests of justice, but is noticeably dejected on watching Abe once again win in a landslide.

His victory seems to stand in for a triumph of patriarchy as Shiori is repeatedly silenced or ignored. The editor also tells her Yamaguchi could stop her book being published because publishing isn’t given the same freedom as the press theoretically has but does not use. Meanwhile, the implication is that the head of the Tokyo Police stopped Yamaguchi’s arrest in order to bolster his own political capital and was in fact rewarded for it later. Shiori seems to develop a friendly relationship with a conflicted policeman who was sympathetic to her case, but even he drunkenly makes a pass at her during an ill-advised phone call that comes off as sexual harassment and is even more inappropriate given the circumstances. The doorman at the hotel meanwhile makes an awkward attempt to centre himself as the hero when agreeing to testify publicly even if it puts his job at risk that she should be grateful it was him who was on duty because he’d always thought the laws surrounding sexual assault were too lenient though he actually did very little to try to help on the night in question even if he did attempt to call the police but was shut down by the hotel.

Nevertheless, his agreement and support bring Shiori to tears while begins to feel isolated and under incredible pressure from those who regard her as someone who can bring real change. Despite an early monologue warning that if she died and they said she took her own life she’d been bumped off, we later see her heading into a very dark place describing the difficulty of living life in her new persona as “that girl who was raped” even if she also receives support from other women oppressed by Japan’s fiercely patriarchal culture. Of course, others call her a traitor to her gender and say they feel sorry for the men she’s accusing. But still she continues undaunted, eventually emerging from the long dark tunnel at the film’s conclusion and continuing to project the sense of support for other women echoed in the opening title cards addressed to those watching who have likely themselves experienced similar trauma.

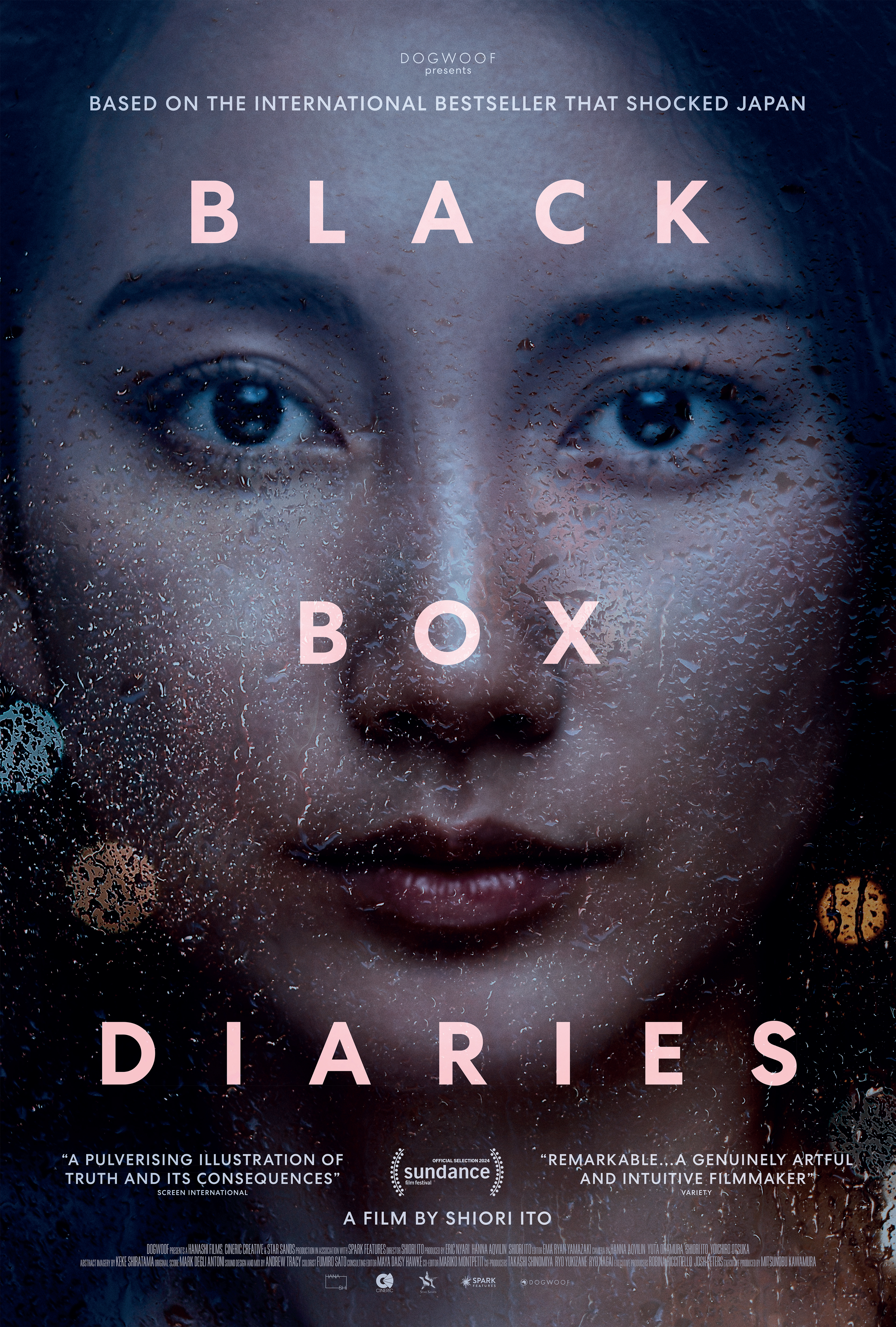

Black Box Diaries screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival and will be released in UK cinemas 25th October courtesy of Dogwoof.

UK trailer (English subtitles)