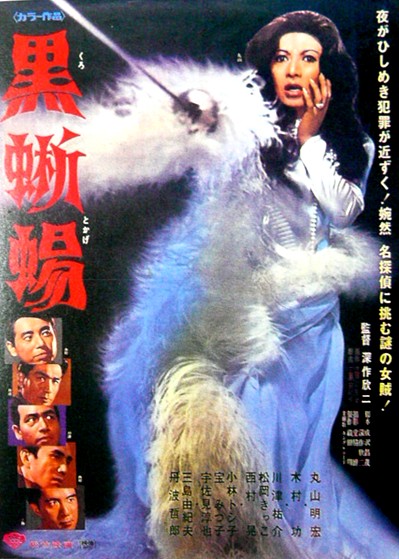

Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.

Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.

The sense of foreboding sets in right from the beginning as Kyohei, club owner and family patriarch, narrates a scene draped in a harsh red filter in which the lynchpin of the entire film, Ryuko, disembarks from a boat onto a jetty to meet him. He warns us that the sight of her was the “calm before the storm”, already anticipating the tumultuous events which are to follow. Having spotted her in a club in Yokohama, Kyohei poached Ryuko to work at his private members bar as a cabaret artist where she duly fascinates the customers seemingly knowing how to appeal to each of their own particular tastes in turn. A short time later, other suitors from the other bars begin to turn up but Ryuko refuses to recognise any of them. She is waiting for true love and believes the black rose she carries will turn red once she meets her prince charming. After a while she decides to move on but Kyohei convinces her to stay and maintain her “illusion” of perfect love rather than continually bursting its bubble, and so the two become a couple. However, when Kyohei’s wayward son Wataru returns and also becomes infatuated with Ryuko, a new chain of tragic events ensues…

Just to add fuel to the fire, the role of Ryuko is played by female impersonator Akihiro Miwa (formerly Akihiro Maruyama) who had also worked with Fukasaku on the notorious Black Lizard. Ryuko is mysterious, exotic maybe, etherial – certainly. She seems to shed identities only to pick up new ones perfectly tailored to whichever man she’s courting hoping each is the one who will turn her black rose red. Each of the previous suitors has failed to make her flower bloom and has so been discounted – erased from her memory whether willingly or unconsciously. When one of them is killed in front of her and her rose splashed with blood turning temporarily red, only then does she look on him lovingly. She loves them as they die but not before or after. Has each of these lonely, “different” men fallen for a siren call from the angel of death, or is Ryuko just another unlucky femme fatale who always ends up with the crazies?

Camp to the max and full of that rich gothic melodrama that you usually only find in a late Victorian novel, Black Rose Mansion is undoubtedly too much of a stretch for viewers who prefer their thrills on the more conventional side. However, there is something genuine underlying all the artifice in the story of obsessive, all encompassing love which develops into a dangerous sickness akin to madness. Ryuko is an unsolvable mystery which drives men out of their minds though they never seem to probe very far into her soul preferring to conquer her body. Only Kyohei who, at the end, is cured of his obsession with her, recognises that Ryuko is a woman who only exists in men’s minds and what you think of as love is really only lust like an unquenchable thirst.

Fukasaku attempts to invert classic gothic tropes by shooting the whole thing in lurid, brightly coloured decadence. Every time Kyohei thinks back on Ryuko he sees her bathed in red, like a beautiful sunset before a morning storm. Like Kyohei and pretty much everyone else in the picture, we too become enthralled by Ryuko and her uncanny mystery, seduced by her strangeness and etherial quality. Yes, it’s camp to the max and drenched in gothic melodrama but Black Rose Mansion also succeeds in being both fascinatingly intriguing and a whole lot of strange fun at the same time.

Black Rose Mansion is available with English subtitles on R1 US DVD from Chimera and was previously released as part of the Fukasaku Trilogy (alongside Blackmail is My Life and If You Were Young: Rage) by Tartan in the UK.

One of the foremost avant-garde filmmakers of the New Wave era (though he detested this term which, in fairness, is a retrospective and often arbitrary label), Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida has remained largely unseen in the West. Some of this is his own fault – fiercely independent, Yoshida nevertheless found himself working with ATG after leaving Shochiku but the relationship was an unusual one and often far from easy. All but the latest film in Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset,

One of the foremost avant-garde filmmakers of the New Wave era (though he detested this term which, in fairness, is a retrospective and often arbitrary label), Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida has remained largely unseen in the West. Some of this is his own fault – fiercely independent, Yoshida nevertheless found himself working with ATG after leaving Shochiku but the relationship was an unusual one and often far from easy. All but the latest film in Arrow’s Kiju Yoshida boxset,