Set in 1984 in a rural Chinese backwater, De Lan (德蘭) is named not for its central character, but for his first love – a mountain woman far from home in search of a missing relative. Tasked with following De Lan (De Ji), Wang (Dong Zijian) finds himself entering a strange new world which he is incapable of fully understanding, not least because he doesn’t speak the language. A wordless love story between the tragic De Lan and the adolescent Wang is destined to end unhappily, but will affect both of them in quite profound ways.

Set in 1984 in a rural Chinese backwater, De Lan (德蘭) is named not for its central character, but for his first love – a mountain woman far from home in search of a missing relative. Tasked with following De Lan (De Ji), Wang (Dong Zijian) finds himself entering a strange new world which he is incapable of fully understanding, not least because he doesn’t speak the language. A wordless love story between the tragic De Lan and the adolescent Wang is destined to end unhappily, but will affect both of them in quite profound ways.

Wang’s father has been missing for three months, and what’s worse is that around 2000 yuan went missing with him. Mr. Wang had been the loans officer for the local party office in this dreary mountain town and now the best idea anyone has come up with is for Wang to take over the position and pay back the missing money with deductions from his wages (this should take around ten years). Hardly fair, but what can you do? Wang’s first assignment is to take an audit of a mountain town where the residents have a lot of outstanding payments. Seeing as they’re heading to the same place, Wang is to accompany a mountain woman, De Lan, who had been travelling around local towns looking for a missing person but has now run out of money and must go home alone.

Wang is told to trust De Lan when it comes to the terrain, but that he should keep control of the food supplies in case she tries to run off. All things considered, the people at the foot of the mountains, aren’t very well disposed to those at the top. Wang is young and unused to walking such long distances, frustrating De Lan with his inability to keep up and frequent needs to rest. Nevertheless a kind of mutual affection seems to build up between them but largely goes unspoken and unacknowledged. Finding himself installed in De Lan’s home, Wang begins to feel very awkward indeed, unable to work out the strange family dynamic between the gruff man with the lame leg, ancient blind old woman, and the feisty De Lan.

Wang has, after all, been sent to the town to collect on loans – an entirely pointless enterprise as no one here has any money. Wang’s father was a much loved presence, mostly because he always came with cash and never pressed them on repayments. His son, with a father’s debt around his neck, is not quite so nonchalant. Calling a village meeting with no notice, Wang makes it clear he won’t be following his father’s lax approach and will not be issuing any new loans, rather he will be calling in the old ones. This does not make him popular in the village.

Eventually he changes his mind and decides to flash some cash but his worst assumptions are confirmed when the villagers, far from using the money they claimed to so desperately need to survive to invest in their businesses, club together to buy all the booze in the surrounding area and have a giant party. Originally put out by their trickery and De Lan’s ongoing unavailability, Wang suddenly finds himself trying some of their liquor and joining in with a dance around the fire. Perhaps learning to adjust to the Earthy, less ordered way of life, Wang has embraced the new found freedom of the place, but he will also discover that it only runs so deep.

De Lan’s life has undoubtedly been a difficult one which she faces with stoic resignation. Shared between two men and longing only for a child, De Lan has very little say in anything that happens to her yet she was able to set off all alone to look for her missing person. During the trip, De Lan is dismayed when a teenage boy in a home they spend a night in makes a vulgar comment about her body, leading her to try to leave as soon as possible only for Wang to pledge his protection. De Lan is aware of the dangers of the road, as well as the constraints placed on her life, whereas as Wang is still naive enough to think his physical strength and government position would be enough to keep De Lan any safer than she would be alone.

As Wang’s feelings for De Lan grow he fantasises about saving her from this strange, cold household though he barely stops to ask himself if saving is really what she wants. Unable to speak the local dialect, Wang necessarily needs to rely on look and gesture which is largely how he and De Lan have come to communicate – a pure kind of dialogue without need of words. Wang’s love for De Lan is destined to cost him dearly both in financial and emotional terms. A beautifully sad tale of frustrated first love set against the picturesque Chinese countryside and inside it’s much less pretty political system, De Lan is the story of one man’s transition from adolescence to manhood through heartbreak, filled with quiet, yet intense, emotion.

Reviewed at the 2016 London East Asia Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)

First time writer/director Wang Yichun draws on her own experiences for What’s in the Darkness (黑处有什么, Hei chu you shenme), a beautifully shot coming of age piece with serial killer intrigue running in the background. Seen through the eyes of its protagonist, What’s in the Darkness neatly matches the heroine’s journey into adolescence with the changing nature of Chinese society.

First time writer/director Wang Yichun draws on her own experiences for What’s in the Darkness (黑处有什么, Hei chu you shenme), a beautifully shot coming of age piece with serial killer intrigue running in the background. Seen through the eyes of its protagonist, What’s in the Darkness neatly matches the heroine’s journey into adolescence with the changing nature of Chinese society. When

When  The best revenge is living well, but the three damaged individuals at the centre of Tomoyuki Takimoto’s Grasshopper (グラスホッパー) might need some space before they can figure that out. Reuniting with

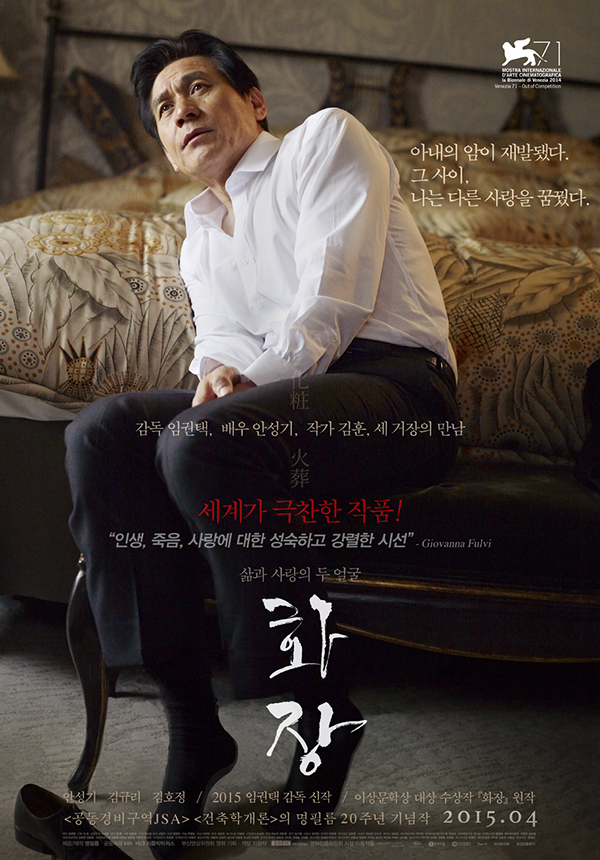

The best revenge is living well, but the three damaged individuals at the centre of Tomoyuki Takimoto’s Grasshopper (グラスホッパー) might need some space before they can figure that out. Reuniting with  The 102nd film from veteran Korean film director Im Kwon-taek may appear close to the bone in its depictions death, suffering, and the long look back on a life filled with the quiet kind of love but Revivre (화장, Hwajang) is anything but afraid to ask the questions most would not want to hear as the light dwindles. The inner journey is just too hazy, as one man puts it, unknowingly commenting on the human condition, yet Im does manage bring us nicely into focus, if only for a moment.

The 102nd film from veteran Korean film director Im Kwon-taek may appear close to the bone in its depictions death, suffering, and the long look back on a life filled with the quiet kind of love but Revivre (화장, Hwajang) is anything but afraid to ask the questions most would not want to hear as the light dwindles. The inner journey is just too hazy, as one man puts it, unknowingly commenting on the human condition, yet Im does manage bring us nicely into focus, if only for a moment.

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process.

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process. Evil, so a wise man said, begins when you start treating people as things. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis showed us a city that literally was its people – nothing but a vast yet perfectly functional machine with the workers little more than cogs to be replaced and discarded once worn out. Zhao’s Behemoth (悲兮魔兽, Bēixī Móshòu) is no fantasy but a very real journey through our own world and so we follow our narrator, a poetic, naked stand in for Dante’s Virgil, through hell and purgatory on a path to paradise only to find ourselves staring into a void filled with our unfulfilled desires and forlorn hopes.

Evil, so a wise man said, begins when you start treating people as things. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis showed us a city that literally was its people – nothing but a vast yet perfectly functional machine with the workers little more than cogs to be replaced and discarded once worn out. Zhao’s Behemoth (悲兮魔兽, Bēixī Móshòu) is no fantasy but a very real journey through our own world and so we follow our narrator, a poetic, naked stand in for Dante’s Virgil, through hell and purgatory on a path to paradise only to find ourselves staring into a void filled with our unfulfilled desires and forlorn hopes. Because it’s there. As good a reason as any for doing anything but these were the only three words of explanation offered by George Mallory in answer to the question “Why climb Everest?”. In Powell & Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, the heroine reacts in a similarly philosophical fashion when asked “Why do you want to dance?” replying with the question “Why do you want to live?”. What makes some people prepared to dance until their feet bleed and their toes break, and sends others to the peaks of snowcapped mountains staring death in the face as they go, is something which cannot be fully explained in words but cannot be denied by those who hear its calling.

Because it’s there. As good a reason as any for doing anything but these were the only three words of explanation offered by George Mallory in answer to the question “Why climb Everest?”. In Powell & Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, the heroine reacts in a similarly philosophical fashion when asked “Why do you want to dance?” replying with the question “Why do you want to live?”. What makes some people prepared to dance until their feet bleed and their toes break, and sends others to the peaks of snowcapped mountains staring death in the face as they go, is something which cannot be fully explained in words but cannot be denied by those who hear its calling.