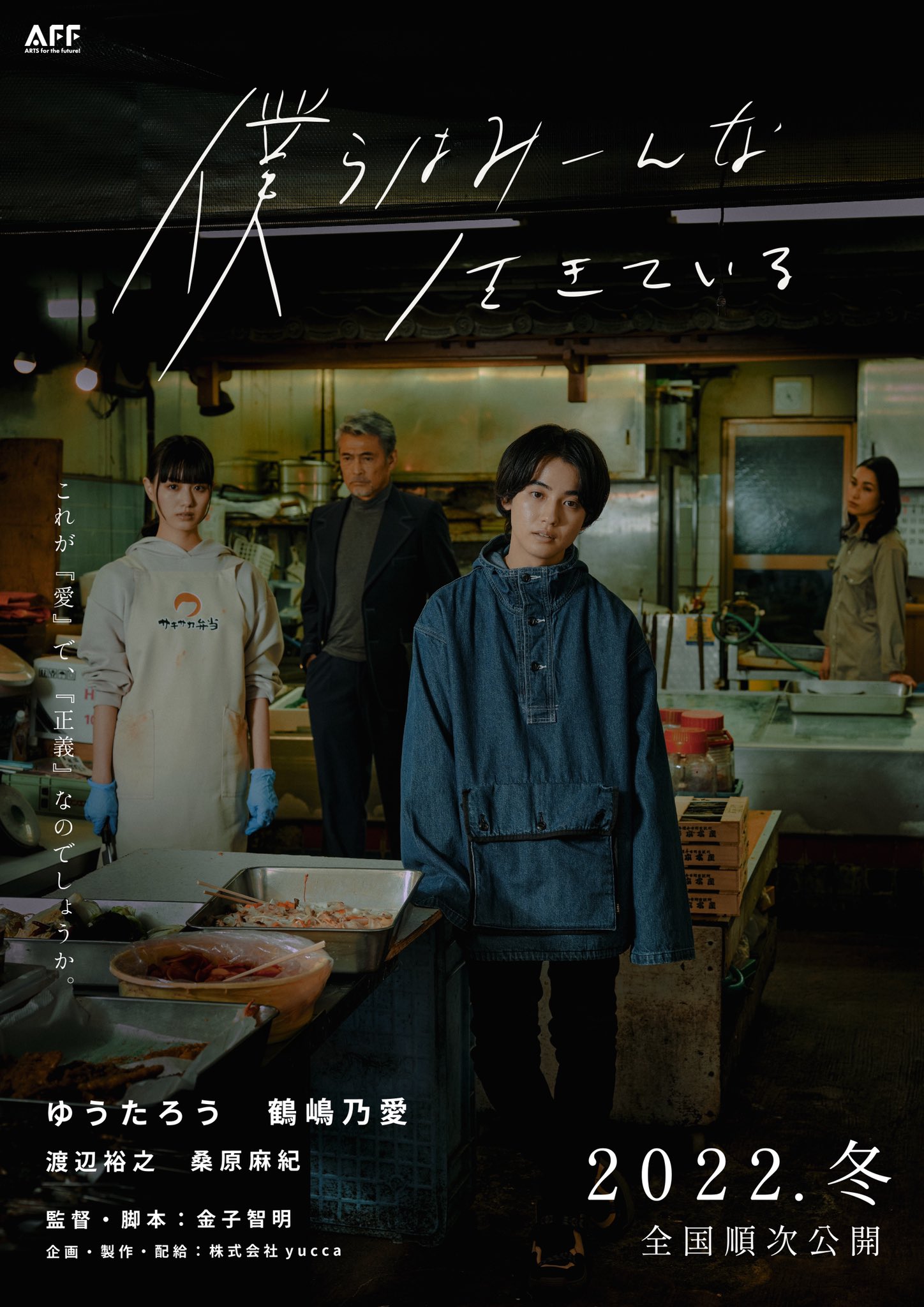

Fearing he knows nothing of the world, a young man comes to Tokyo in search of experience but finds his horizons broadened a little more than he might have liked in Tomoaki Kaneko’s bleak indie drama Dead Fishes (僕らはみーんな生きている, Bokura wa Minna Ikiteiru). Legacies of poor parenting, either from an overabundance of love or.a lack of it, continue to cast a shadow over the futures of the young while love otherwise makes people do funny things that defy both logic and humanity.

One of the key reasons Shun (Yutaro) leaves his rural hometown is to get away from his parents and their tempestuous marriage though it’s also true that his mother has become more than a little possessive and he clearly does not want to end up trapped by her all his life. He dreams of becoming a writer, but tells new friend Yuka (Noa Tsurushima) that writing for him was more of an escapist than artistic exercise. Most of his books are of the kind where nothing really happens, a kind of wish fulfilment writing stories about the happy family he never had in which parents and children enjoy cheerful days out at the beach or the zoo, which is why he suspects publishers aren’t biting.

But Yuka has parental resentments too, explaining that her mother took her own life after her father abandoned them before she was born. She has a healthy distrust of adults and the in-built cynicism of someone twice her age but also resents herself for having been unable to enact revenge on her absent father. Nevertheless, she feels sympathy for the old people living in the local care home who have also been, according to her, “abandoned” by their families who no longer wish to care for them. Their boss, Yuriko (Maki Kuwahara), is currently caring for her mother who is suffering with dementia and occasionally becomes violent or refuses food though as the pair discover she is also mixed up with her much older boyfriend’s heinous scheme to help overburdened children knock off their elderly relatives through slow poisoning or an “accident” in return for a portion of their life insurance money.

The scheme both bears out the corrupted relationship between parent and child and the darkness of the contemporary society in which, as the Chairman (Hiroyuki Watanabe) says, the elderly can benefit their families only by dying. Despite having become aware of the goings on at the bento shop, neither Yuka nor Shun are particularly motivated to do anything to stop them, simply living on in resentment or disapproval. Yuriko tells him that he can’t understand her actions because he’s too young and has never been in love, but it’s also true that she was supposed to get a healthy payout for the slow poisoning of the man the Chairman made her marry for appearance’s sake who is likewise aware they’re planning to kill him but basically allowing them to because of love. Love is also the justification Shun’s mother gives when she arrives unnanounced and ends up talking to Yuka, explaining that she’s never thought Tokyo was right for her son so she’s found him a job back home which is after all not really her decision to make.

But then again even Shun’s writing dreams become corrupted by the city when he’s hired to write a column for a pornographic magazine that’s only distributed in local brothels. Even the editor who hires him appears beaten down and desperate, explaining that he was once a writer too but seemingly ashamed of his current profession later decided to cut his losses and return to his hometown stopping to warn Shun only not to turn out like him or to let himself be changed by the environment he now finds himself in.

By contrast, Yuka’s flighty roommate Mika (Haruka Kodama) says she’d rather die than live with dead fish eyes escaping from her own despair and disappointment through casual sex work to supplement her income from working at a black company. Claiming that all you need in life is a money and good reputation, she’s planning to string this out until the end of her 20s in the hope of meeting a nice man to settle down with for a traditional housewife existence. Bleak in the extreme, Kaneko leads this moribund small town a sense of futility and emptiness and sees little way out for an orphaned generation other than to surrender themselves to the indifference of the world around them.

Original trailer (no subtitles)