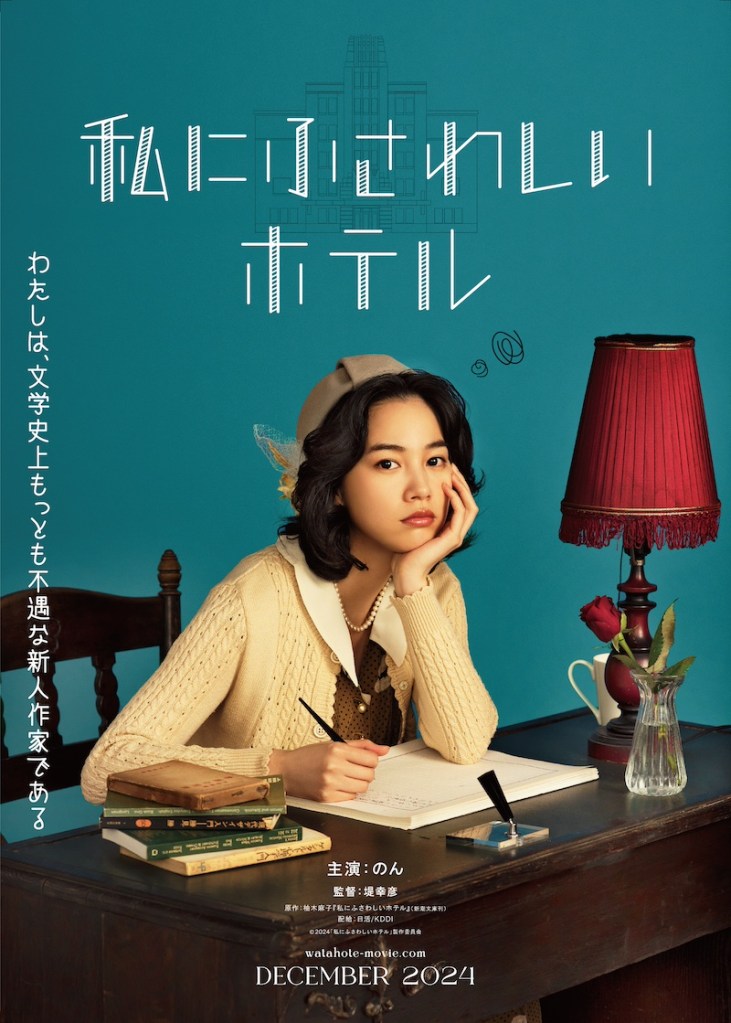

What does a girl have to do to get her book published in this town? Adapted from the novel by Asako Yuzuki, Yukihiko Tsutsumi’s The Hotel of My Dream (私にふさわしいホテル, Watashi ni Fusawashi Hotel) follows its eccentric heroine through a literary feud with an established master in an attempt to defeat a misogynistic, hierarchal and exploitative publishing industry and finally publish a full-length novel. In part a meditation on identity, the trades on its heroine’s charms and the comedic prowess of leading lady Non.

Set in 1984, the film begins and ends at the Hilltop Hotel popular with writers through the ages thanks to its proximity to book town Jinbocho and the offices of big time publishers. Using the pen name Taiju Aida, Kayoko (Non) is an aspiring author who won her publisher’s newcomer prize a few years previously for a short form essay but has been unable to write anything of substance since after being stung by a harsh review from literary master Higashijujo (Kenichi Takito). After learning from her editor Endo (Kei Tanaka) that Higashijujo is in the room upstairs and is on a tight deadline to complete a story for an upcoming anniversary anthology, Kayoko decides to impersonate a hotel maid so he’ll stay up all night and not make it, forcing Endo to use her story instead.

The irony is that Kayoko’s story is popular with readers and she has real talent as a writer that’s being suppressed by the publishing industry at large in the form of her former publisher, Endo, and Higashijujo. Higashijujo is a representative of a particular kind of older writer and is effectively acting as a gatekeeper by suggesting that young women like Kayoko have no place in the literary scene. Even so, he’s captivated by the story she tells him that’s the same as the essay she later has published which cleverly weaves in some of his own personal details. She plays on his vanity and lasciviousness in telling him she’s a big fan and is romantically naive as if dangling herself as bait. Higashijujo realises that Kayoko is Taiju Aida and kicks off a kind of literary feud in which he disrupts her career and she puts on various different personas to upset or embarrass him.

Nevertheless, his rivalry with her does seem to stimulate his own latent artistic mojo and have him writing manically once again if partly out of resentment, while Kayoko is forced to change her name again before winning a note literary prize as “Junri Arimori” and writing with a completely different style. On realising that they may both be being manipulated by Endo who is setting them against each other in order to stimulate their writing, they team up against him by attempting to disabuse his daughters of the notion that Santa’s not real only they already know. They were just going along with the ruse because that’s a child’s job in much the same as Higashijujo suggests a writer’s is to conjure a pleasant fantasy for the reader and Kayoko creates a series of false personas further her own literary dreams.

Yet as Kayoko says she’s not given the kind of support that other writers get and even after getting a book published has to go round to stores on her own to encourage them to stock and promote it. She only rises to prominence by charming a bookseller after catching a notorious book thief who didn’t even steal hers because he only takes “popular” books. Kayoko is indeed a total crazy lady, but perhaps you need to be in order to survive in this environment that’s still dominated by men like Higashijujo writing borderline sleazy novels and hanging out with hostesses in upscale Ginza bars. Resented by his daughter, he stays out in hotels for days at a time, leaving his wife alone and neglecting his family. Kayoko has to fight tooth and nail for her place in this space and to prove herself worthy of a room at the Hilltop Hotel while Higashijujo’s ride was must less fraught with difficulty even if it may not have been easy. The final message seems to be, however, that art is created best in opposition and success isn’t always good for an artist as Kayoko finds herself frustrated, feeling as if she hasn’t achieved all of her revenge but has no left to take it against while perhaps still manipulated by Endo who provides a source of authority for her to kick back against as literary queen trying to hang on to her throne.

The Hotel of my Dream screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Images: © 2012 Asako Yuzuki_Shinchosha © 2024 “The Hotel of my Dream” Film Partners