The ethics surrounding the organisation of religion can often be thorny, yet the issue is less one of practice or philosophy than of the potential exploitation of vulnerable people in search of spiritual support. Titled “Come and See” (เอหิปัสสิโก) after an exhibition organised by the religious organisation at its centre in order to debunk the “fake news” and frequent attempts at what it describes as defamation in the mainstream press, Nottapon Boonprakob’s documentary investigates not only the controversial Buddhist sect Dhammakaya and its former abbot Dhammachayo (missing since 2017) but the place of Buddhism in modern Thai society which was under the rule of a military junta until the summer of 2019 following a 2014 coup.

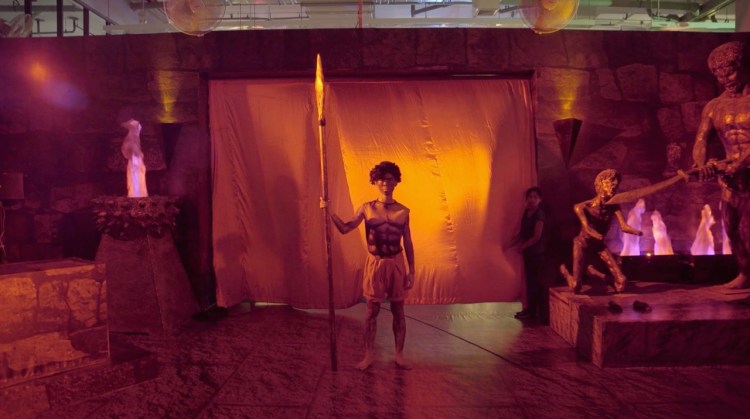

Founded in 1970, the controversial sect is said to have over four million devotees with 131 temples located around the world and operates out of a vast religious complex centred in a building which resembles a giant spaceship with a large eye-shaped orb. It has caused controversy with practitioners of Buddhism firstly because its teachings run in contrast with traditional religious thought in suggesting that Nirvana is a physical rather than purely spiritual place and that it is possible to meet the Buddha as founder monk Dhammachayo claims to have done. Doctrinal issues aside, however, many view the sect with suspicion because of its aggressive fundraising programme while Dhammachayo has also been directly accused of money laundering and the receipt of stolen goods. The temple deflected the accusations on the grounds that Dhammachayo’s age and ill health prevented him from responding fully while his followers later insisted he would turn himself in but only once Thailand retransitioned to full democracy. Following a lengthy siege of the temple building it was however discovered that Dhammachayo was not in his “recovery room” as aides had stated but apparently missing, perhaps in hiding. His whereabouts are currently unknown.

Using a mixture of talking heads interviews with current and former members as well as religious experts alongside documentary footage, Nottapon Boonprakob does not directly investigate the various allegations but sets them against the contemporary Thai society. The sect itself and some of the experts even those on the opposing side believe the charges are at least in part politically motivated, that given its vast wealth and huge number of followers it is in danger of becoming a state within a state and therefore presents a threat to the traditional authorities. This level of destabilisation is thought to have contributed to the military coup which took place in 2014 and is posited as an explanation for the junta’s determination to weaken the temple’s reach though in the continuous absence of Dhammachayo its efforts would seem to have proven fruitless.

Nottapon Boonprakob follows one particular devotee as she takes part in the resistance movement to the police investigation eventually moving into the temple compound which is later placed into a lengthy siege during which two people sadly pass away, one from an asthma attack and the other apparently a suicide committed in protest (though the temple disavow this action and claim the man was not a follower). Devotees are heard to offer their lives for the abbot, perhaps disturbingly citing that dying for something when everyone dies anyway will buy them more “merit” and thereafter a secure place in the highest levels of heaven. Devotees can earn merit by donating monetarily to the temple or by completing other tasks as we see them do during the siege though it is perhaps strange that we only seem to see the women cleaning and cooking even if they also seem to make up a larger percentage of the devotees captured on film. It was this increasing concentration on “fundraising” with “sales” quotas set for monks that drove one former practitioner away, explaining that she felt under pressure to continue donating eventually becoming disillusioned with the materialist bent of the sect’s practice which she now feels is corrupting Buddhism in Thailand.

Another former member who worked for the organisation says something similar, that he attempted to raise the matter with Dhammachayo after a practitioner came to him with a marital dilemma. Her husband had apparently walked out and she had devoted herself entirely to worship in order to get him back, selling inherited properties to buy more merit and wondering if she should sell the house she was living in too. While he worried the woman’s intense practice may have further strained her marriage and she should not perhaps be encouraged to bankrupt herself for religious reward, he claims that Dhammachayo coldly told him that he was no longer Dhammachayo the monk leaving him frightened and disillusioned. He subsequently resigned and joined another sect, becoming an outspoken critic of Dhammakaya claiming that Dhammachayo had attempted to convince him he was the “Creator of Everything”.

Other commentators meanwhile wonder if the ritual practice at the temple which takes place at grand scale featuring huge parades with much pomp and circumstance is merely an “extreme” expression of Thai Buddhism and perhaps reflects something of the contemporary society. Some describe it without judgement as “capitalist Buddhism”, providing a service that responds to customer’s desires and profiting by it as in any other business while others wonder if Buddhism has or should have any real relevance in 21st century Thailand. It is however the sect’s potential power to interfere in the mechanisms of government through complex networks of influence that has many alarmed, and is perhaps the reason they find themselves targeted by the regime while many other organisations similarly accused of corruption are largely ignored. In any case, the temple seems to have come out on top, the police forced to abandon their search in the continued absence of the abbot. Nottapon Boonprakob offers no real conclusion but as an interviewee points out independent enquiry is a central tenet of Buddhism, “come and see” for yourself.

Come and See streams in the US March 24 – 28 as part of the 12th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)