“Japanese society is definitely worse than it was five years ago” according to director Tatsuya Mori, returning to the subject of Aum Shinrikyo following his 1998 documentary A, “It is definitely warped.” In A2, he wonders if the legacy of the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway has affected society in unexpected ways as its rage and fear is channeled in the wrong direction in its pathological hatred of the new religion sect without attempting to understand why the attack happened or why people continue to follow the cult’s teachings given its violent history.

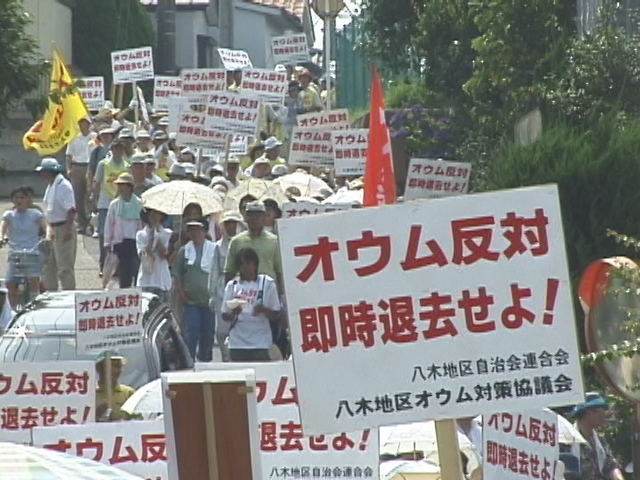

Five years on, Aum has rebranded as Aleph and distanced itself from the teachings of Shoko Asahara but is still holding out on coming up with a plan for compensating victims and their families while some members directly involved in the attack remain on the run (the final fugitive was apprehended only in 2012). The government has decreed that those who had no connection to the incident should be allowed their constitutionally guaranteed rights to practice their religion, but as Mori follows them the current members face constant harassment in the local communities in which they attempt to settle. As someone later puts it, there is no real solution, once Aum is rejected they have no option but to move on to another town where the same thing will happen again with no real progress made.

Even so, in one particular community the locals become almost friendly to the Aum members they are also keeping under close and intensive surveillance. Though instructed not to interact with them, some residents explain that they personally would prefer to be on friendly terms, others jokingly even offering them food or alcohol over the fence and almost sorry to see them leave when their rental contract finally expires. Through their admittedly hostile interactions, they’ve come to accept the members of Aum as distinct from their association with the sarin gas attack and no longer harbour the same sense of fear they once held for the unknown quantity of the new religion organisation.

On the other hand, the fear and anxiety which has become linked with Aum has been hijacked by right-wing nationalist groups seeking to manipulate it for their own gain as they step into the vacuum created by a lack of action with their own ideas for potential solutions to the Aum problem. Their solutions are not as extreme as one might assume, but advocate for Aum’s forced disbandment with no practical plans for how that might happen. As Aum members admit, as a new religion organisation they often attract those who are vulnerable and looking for solutions to their own mental anguish. Faced with the intense harassment they face in smaller communities, these members are often pushed towards taking their own lives while the press has sometimes also attempted to manipulate their image for personal gain one man claiming he was essentially abducted and taken to hospital on the grounds he seemed malnourished but was prevented from leaving after getting the OK from a doctor as the police had already issued a statement about him which the press had printed without verifying.

The current Aum members frequently complain that they have been misrepresented by the press while Mori himself is on one occasion accused of being an Aum sympathiser when challenging potential inaccuracies or asking if those participating in anti-Aum activity might be better off trying to understand them instead. This seems to be the direction in which some of the protests have drifted, local societies putting up signs to encourage thse who might want to leave the organisation to reassure them that they will be reaccepted by mainstream society, that their friends and relatives with whom they have severed ties are waiting for their return. The members, however, are often so disconnected from “worldly” matters that they may not know what mainstream society is, Mori’s brief questioning of an official revealing that she is unable to recognise the names of even the biggest contemporary pop stars. “Ultimately harmony can’t be achieved, can it?” Mori asks somewhat rhetorically, worrying that the psychological strain placed on the followers not only in the austerity of their religion but their treatment by wider society cannot but lead to further damage while opinions on either side are unlikely to soften.

A2 streams worldwide (excl. Japan) via DAFilms until Feb. 6 as part of Made in Japan, Yamagata 1989 – 2021 (films stream free until Jan. 24)

Original trailer (no subtitles)