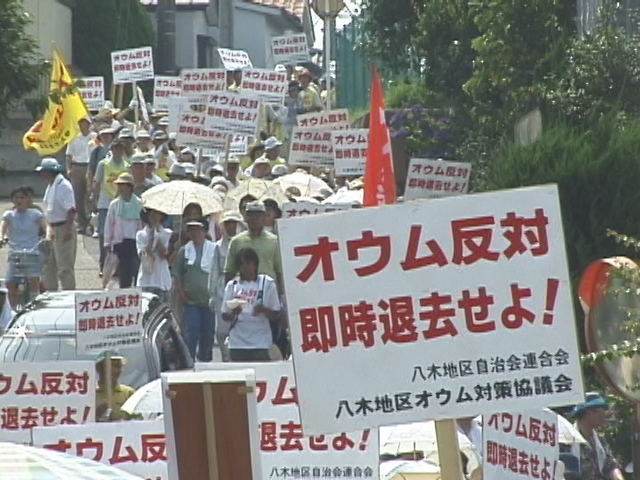

After the devastating Great Kanto Earthquake struck in 1923, it led to a period of hysteria in which in the natural disaster somehow became equated with the Korean Independence Movement, foreigners, and socialists and who were after all thorns in the side of rising nationalism. Documentarian Tatsuya Mori makes his narrative film debut with September, 1923 (福田村事件, Fukudamura Jiken) released to mark the 100th anniversary of the incident and focussing on a little known episode in which villagers turned on a small group of itinerant medicine pedlars they were convinced were not Japanese.

In this case, at least, they were Burakumin. An oppressed underclass of their own, they too are divided in their views about Koreans some finding solidarity with them as another minority who is bullied and discriminated against while others are quick assert themselves as at least being above them on the pecking order cheerfully using slur words as they go. Shinsuke (Eita Nagayama), the leader of the troupe, laments that they have to live this way, tricking those worse off than themselves into buying their snake oil cures while explaining that though people will often help each other out when times are good, if survival’s on the line they’ll turn against each other.

Perhaps that’s difficult to imagine in a small village of genial farmers, but militarism has already corrupted its gentle rhythms. Men from the village are fond of telling war stories from their time as conscripts in China or Russia, though one has a particular bee in his bonnet about wives being left lonely with husbands away overseas and is convinced that his father has slept with his wife. Another local woman was indeed having an affair shortly before her husband was killed in action and is then ostracised by the village for her transgressive behaviour becoming yet another oppressed minority. The village chief is keen on democracy and progressive in his way yet soon finds himself powerless against the local militia mostly comprised of old men with a lust for blood and glory. It’s this militarist hysteria that eventually proves tragedy as they find themselves desperate to identify “spies” and protect the village only to murder children and a pregnant woman who were just passing through.

The absurdity extends to asking those suspected of being Non-Japanese to repeat a particular phrase difficult for Koreans in particular to pronounce, only those from other areas of Japan also pronounce it in a way that might seem “foreign” in Tokyo. Cornered by the militia, Shinsuke asks if it would be alright to kill him even if he were Korean, taking issue with the militia’s absurdist and racist rationale that decides someone must die because of the way they pronounced a certain word or seemed uncomfortable shouting “banzai” at the point of a sword. But one of the villagers unwittingly uncovers a since of guilt felt even by a man in a village miles away from anything that the Koreans have been bullied for years, this the understandable result of their rage boiling over and a moment of retribution.

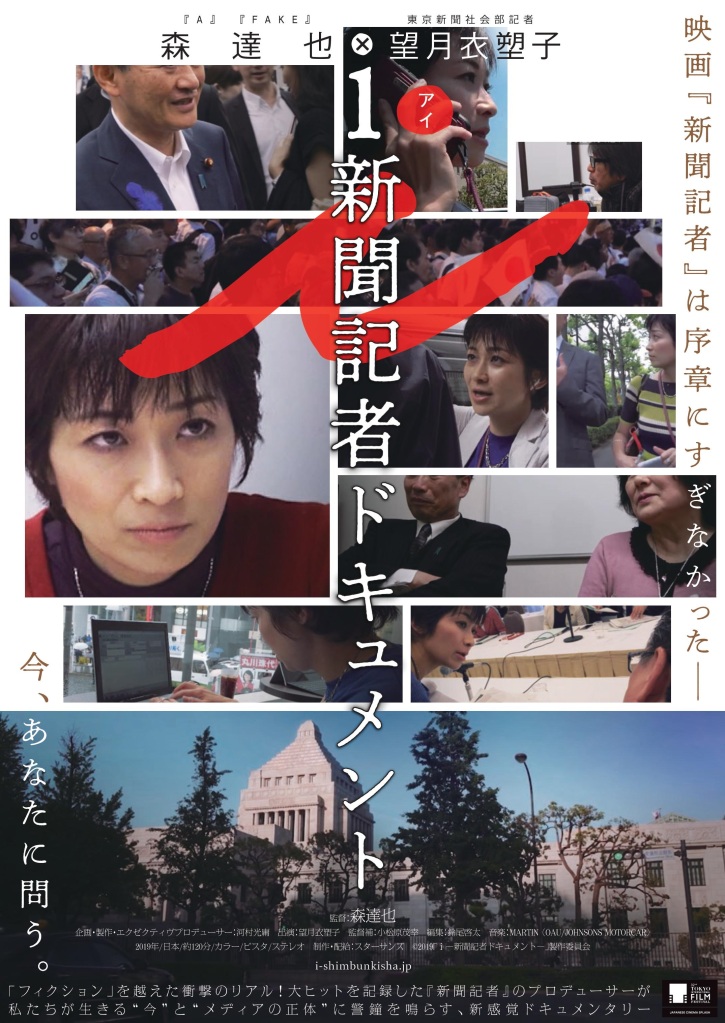

The film seems to suggest that the buck doesn’t really stop, except perhaps with the bystander who merely watches this horrifying violence and does nothing. Tomokazu (Arata Iura) has recently returned to the village after many years living in Korea bringing back with him a Korean wife but his marriage is falling apart due to his own guilt and trauma having been complicit in a Japanese atrocity. Watching the massacre unfold, his wife, Shizuko (Rena Tanaka), asks him if he’s just going to watch this time again but his attempt to intervene makes no difference. An idealistic news reporter meanwhile takes her boss to task for publishing propaganda headlines associating Koreans with crime and terrorism rather than real truth of what’s happening on the ground, asking him what the point of the press is if it won’t speak truth to power. But militarists do not listen to reason, and as the headman points out they will have to keep living with those who’ve committed these heinous acts. Sometimes a little on the nose with its symbolism such as a literal murder of hope in the killing of an unborn child, Mori’s otherwise poignant drama lacks the impact it strives for but nevertheless addresses a shocking moment of mass hysteria that is not quite as historical as we’d like to think.

September 1923 screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection

Original trailer (English subtitles)

In the post-

In the post-