The “literary film” was beginning to fall out of favour by 1969. The collapse of the quota system introduced under the 1962 Motion Picture Law, the exclusion of literary film from the “Domestic Films of Excellence” programme (which encouraged producers to produce high quality Korean films to qualify for distributing more lucrative foreign ones), and the rise of television all conspired to produce a shift towards the populist. Lee Seong-gu had made his name with a series of literary adaptations which enabled him to experiment with form in the comparatively more elevated “arthouse” arena but with horizons shrinking even he found himself with nowhere left turn. Seven People in the Cellar (지하실의 7인 / 地下室의 七人 *, Jihasil-ui Chil-in) is Lee’s last “literary film” and is adapted from a stage play by Yun Jo-byeong who was apparently unhappy with Lee’s adaptation in its abandonment of his carefully constructed ideological balance in favour of adhering to the typical rhetoric of the “anti-communist” film.

Set towards the end of the Korean War, Seven in People in the Cellar presents itself as a conflict between the godless and hypocritical forces of communism and the good and righteous Catholic Church. Accordingly, our hero is a priest, Father Ahn (Heo Jang-gang), who has just returned to his church after being forced to flee by the encroaching “puppet army”. Accompanied by a nun, Lucia (Yun So-ra), and a new curate, Brother Jeong (Lee Soon-jae), Father Ahn is glad to be reunited with his flock but there are dark spectres even here – Maria (Yoon Jeong-hee), a young woman Ahn was forced to leave behind when he fled, runs away from the priest on catching sight of him, apparently out of shame. Meanwhile, while Ahn was away, three rogue Communists began squatting in his cellar waiting for the “reinforcements” which are supposedly going to retake the town. Taking Sister Lucia hostage, the Communists force Ahn to feed them while keeping their existence a secret. To Jeong’s consternation, Ahn agrees but out of Christian virtues rather than fear – he feels the Communists too are lost children of God and have been sent to him so that he may guide them back towards the light.

Not a natural fit for the world of the anti-communist film, Lee does his best to undermine the prevalent ideology even if he must in the end come down hard with Ahn’s essential moral goodness. Thus, Communists aside, the conflict becomes one of age and youth, male and female, as much as between “right” and “wrong” or “North” and “South”. Jeong, youthful and hotheaded, lacks Ahn’s Christian compassion – he bristles when Ahn immediately sets about feeding the starving villagers with their own rations, and disagrees with his decision to harbour the Communists even while knowing that Lucia’s life is at stake if they refuse. Twice he tries to kill the communist “enemy”, threatened by their ideological opposition to his own cause – once when he enters the cellar and misinterprets an altercation between Lucia and sympathetic soldier Park (Park Geun-hyeong), and secondly when the troop’s female commander, Ok (Kim Hye-jeong), attempts to seduce him.

Sexuality becomes spiritual battleground with Christian chastity winning out over Communist free love. Ok, as unsympathetic a communist as it’s possible to be, is sexually liberated and provocative. She suggestively loosens her shirt and fondles her breast in front of a confused junior officer, later taking him into the forest and more or less ordering him to make love to her (which he, eventually, does). However, it is to her simply a matter of a need satisfied. Ok describes the moment she has just shared with her comrade as no different than sharing a meal. She was “hungry”, she ate. When she’s hungry again she will eat again but there’s no more to it than that and there is no emotional or spiritual component in her act of “lovemaking”, only the elimination of a nagging hunger.

Ok’s transgressive and “amoral” sexuality is contrasted with that of the abused Maria who was tortured and later raped by the Communists’ commanding officer. Forced to betray a nun, she was robbed not only of her innocence but also of her faith. Maria is the “pure woman” corrupted by Communist cruelty. Her chastity was removed from her by force, and she sees no other option than to continue to ruin herself in atonement for her “sin”. Unable to live with the consequences of her actions, she sees no way out other than madness or martyrdom.

The fact that Maria’s torturer is another woman, and such an atypical woman at that, is another facet of the Communist’s animalistic inhumanity. As in The General’s Mustache, the Communists are seen to use innocent children as bargaining chips when ordinary torture fails, even this time killing one to prevent him telling the village about their hiding place. Yet the height of their cruelty is perhaps in their indifference to each other – Park, touched by Sister Lucia’s refusal to leave when he tried to let her go fearing that he would face reprisals, announces his intention to defect to the South and is shot dead by his commander in cold and brutal fashion. Park’s defection is a minor “win” for Ahn who sought restore the Communists’ sense of humanity and bring their souls to God, but it’s also born of misogynistic pique in his intense resentment of the “bossy” Ok who turns out to be an undercover officer from HQ on a special mission to spy against him.

With the one redeemed Communist dead, all that remains is for the others is to slowly destroy themselves. Ahn, cool and composed in absolute faith, waits patiently certain that the friendly South Korean soldiers will shortly liberate them. A hero priest, Ahn is the saintly opposite of the Communists’ cruelty in his compassionate determination to save them even at the risk of his own life. Lee keeps the tension high, creating siege drama that feels real and human in contrast with the often didactic and heavily stylised narrative of the “anti-communist” film, subtly muddying the essential messages but allowing Ahn’s compassion (rather than his “faith”) to shine through as the best weapon against oppressive inhumanity.

Seven People in the Cellar is the fourth and final film included in the Korean Film Archive’s Lee Seong-gu box set. Not currently available to stream online.

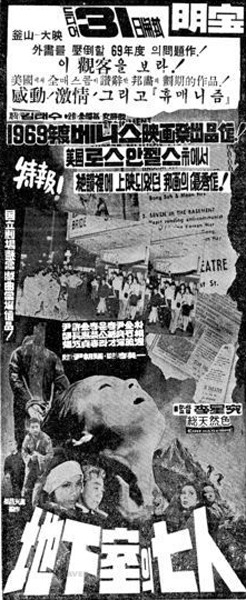

* In rendering the Hanja title, the landscape poster uses the arabic numeral 7 while the portrait version uses the Chinese character 七.