In the early 1960s, tokusatsu movies had begun to slide towards something which was much less serious than the early days of the genre, but as the decade went on others edged in the direction of the ‘70s paranoia thriller expressing a nihilistic view of contemporary Cold War geopoliticking. Given the rather provocative English title Genocide (昆虫大戦争, Konchu daisenso), as opposed to the more recognisably genre-inflected “great insect war”, Kazui Nihonmatsu’s wasp-themed disaster film is part anti-nuclear eco-treatise and part anti-US spy movie.

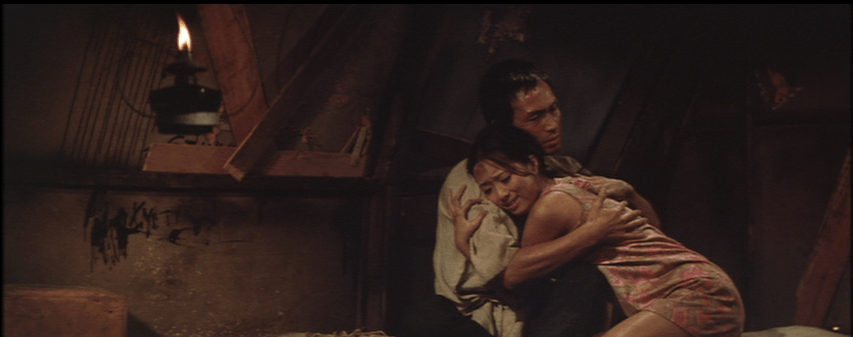

Then again, the film’s secondary hero, Joji (Yusuke Kawazu), a Japanese man obsessed with collecting rare insects he sends alternately to a researcher in Tokyo and a foreign woman living locally, cannot exactly claim the moral high ground. When he spots a US bomber falling out of the sky and runs to investigate the descending parachutes, he’s in the middle of tryst with Annabelle (Kathy Horan) while his wife waits for him patiently at home. Not only that, he picks up an expensive watch dropped by one of the airmen and attempts to sell it, he later claims to buy something nice for his wife, Yukari (Emi Shindo). Meanwhile, the voice of reason Dr. Nagumo (Keisuke Sonoi) is also seen conducting experiments on animals, injecting insect venom into a squirming guinea pig while explaining that the toxin affects the nervous system and causes madness and death.

For all his own moralising, it’s this callous and selfish disregard for life which caused so many problems. The insects have apparently become fed up with human volatility and have decided that they don’t care what humans do to each other but they won’t go down with us in a nuclear war so the only solution is total eradication. The film’s true moral centre, the innocent Yukari, had tried to stop Joji capturing insects, reminding him that “insects have babies too,” while unbeknownst to him the insects he’d been capturing for Annabelle had been used for her sinister experiments to “breed vast numbers of insects that drive people mad and scatter them across the world.”

Annabelle’s quest is one of revenge, claiming that she doesn’t trust humans and likes insects because they don’t lie. She’s currently working with Communist spies supposedly researching deadly nerve toxins but with no loyalty to the regime, only the desire for the eradication of humanity in revenge for the murder of her parents in the holocaust. The Americans, meanwhile, only care about getting the H-bomb that the downed bomber had been carrying, eventually admitting that they’re considering simply detonating it to wipe out the insect threat in total indifference to the lives of those who live on the islands. When Nagumo challenges him, the American officer pulls a gun. One of the soldiers refuses the command to detonate, but is then killed.

The Americans reject the idea that it was “insects” that brought the plane down, but tell on themselves on insisting that the airman onboard was hallucinating having become addicted to drugs to help him overcome his fear of combat situations. The insects do indeed cause him to hallucinate but with flashbacks back to his time in Vietnam, loudly exclaiming that he won’t go back there before asking for more drugs and being injected by a medic. The American officers claim they’re fighting for “freedom and independence,” but it rings somewhat hollow and is immediately challenged by Nagumo. “Sacrifices must be made in war,” they retort when he points out that detonating the bomb will not only kill everyone on the islands but irradiate the rest of Japan, wiping out the Japanese as if they too were merely insects.

Even so, Nagumo too wants to wipe out the insects rather than consider the implications of their concern or find a way to live with them. Annabelle might have had a point when she said that human beings only knew hate despite her entirely twisted and exploitative plan to use the insects to complete her mission of eradicating humanity. In any case, in contrast to other similarly themed films, Nihonmatsu keeps things fairly realistic despite the outlandishness of the narrative, frequently cutting back to closeup footage of an insect biting into human flesh with its pincers before ending on an image of a nihilistic and internecine destruction that suggests there may be no real hope for us after all.

Suffice to say, if someone innocently asks you about your hobbies and you exclaim in an excited manner “blackmail is my life!”, things might not be going well for you. Kinji Fukasaku is mostly closely associated with his hard hitting yakuza epics which aim for a more realistic look at the gangster life such as in the

Suffice to say, if someone innocently asks you about your hobbies and you exclaim in an excited manner “blackmail is my life!”, things might not be going well for you. Kinji Fukasaku is mostly closely associated with his hard hitting yakuza epics which aim for a more realistic look at the gangster life such as in the