You could say Sion Sono is back, though with six films released within a year it’s almost as if he just nipped out to make a cup of tea. At first look Tag (リアル鬼ごっこ, Riaru Onigokko) seems as if it might be towards the bottom of the pile – school girls running away from things for 90 minutes whilst contending with awkward gusts of wind, but this is Sion Sono after all and so there’s a whole world of craziness going on below the surface.

You could say Sion Sono is back, though with six films released within a year it’s almost as if he just nipped out to make a cup of tea. At first look Tag (リアル鬼ごっこ, Riaru Onigokko) seems as if it might be towards the bottom of the pile – school girls running away from things for 90 minutes whilst contending with awkward gusts of wind, but this is Sion Sono after all and so there’s a whole world of craziness going on below the surface.

The action begins with a gaggle of school girls on a bus. Two of them start ribbing the girl on the opposite bank of seats, Mitsuko (Reina Triendl), because she’s always writing poetry. The pen gets knocked out of her hand and as she bends down to pick it up she notices a white feather stuck to the clip. Gazing at the improbable symbol, Mitsuko becomes the only survivor when a sudden gust of wind blows the top off the bus taking all of the other passengers’ heads with it. Mitsuko starts running, re-encountering the dreaded wind monster over and over again before stopping at a stream to wash the blood off her face and change into the cleaner set of clothes she finds abandoned there.

After this she finds herself ending up at an entirely different school where everyone seems to know her. Has she gone mad, had a psychotic break? If not then then she’s about to as an attempt to ditch class with some of the other girls results in yet another freak school girl apocalypse.

Running again, Mitsuko ends up at a police box where another woman seems to know her but insists her name’s Keiko (Mariko Shinoda). Oh, and it’s her wedding day today! That’s not even the last time that’s going to happen and it’s far from the weirdest thing that’s going to happen to Mitsuko today. As a friend of Mitsuko 2’s reminds us, “Life is surreal, don’t let it get to you”.

Answers come, after a fashion. Though Tag is nominally based on a novel by Yusuke Yamada (previously adapted into a long running film series), Sono apparently did not even read the book and has only taken its theme – everyone with the same surname being hunted down and exterminated, and repurposed it for his own ends. This time rather than a common surname, it’s an entire gender that is forced to live under constant threat as the plaything of a far off entity that is as invisible and ever present as the wind. It’s no accident that everyone we meet up until the half way point is female, and that the first (presumed) male we meet is wearing a giant pig’s head. Mitsuko and her cohorts have in fact been used as a literal toy by the men on the other side of the curtain. Their very DNA has been co-opted for the “entertainment” of the male world without their consent or even knowledge, and even if she had known, Mitsuko is powerless to resist.

The solution that is found is both very old and very profound. It’s far from an original ending to this kind of story though in these hands, and used in this way, it can, and has, caused offence. Tag wants to ask you about life, about death, about agency and misogyny – but it wants to ask you all those things whilst watching school girls get ripped apart by the same wind that keeps blowing their skirts up. Sono has his cake and eats it too. There will undoubtedly be those that feel that far from satirising mainstream attitudes to women, Sono has, in fact, indulged in the worst parts of them.

If all of that was sounding a little heavy, Tag runs (literally) at breakneck speed with barely any time for conscious thought between the first bizarre case of gore filled mass murder and the next. It’s also strangely beautiful with a hazy, dreamlike veneer full of repeated images and scenes of idyllic serenity. Is any of this real? Who could really say. The ultramodern, indie score also strikes a slightly hypnotic note lending to the feeling of freewheeling weightlessness.

In many ways, Tag has much more in common with early Sono hit Suicide Club thanks to a general thematic sensibility than to any of his more straightforward work since. That said, Tag never quite resolves itself in a wholly satisfying way and though its final moments are filled with a poetic sensitivity, there’s a certain barrier created by its ambiguity that feels unfinished rather than deliberate. Another predictably “not what it looks like” effort from Sono, Tag may just come to be remembered as his most considered effort of 2015.

First Published on UK Anime Network in November 2015.

Playing at the Leeds International Film Festival on 18th November 2015.

Other movies playing at Leeds include Assassination Classroom, Happy Hour, Our Little Sister and Love & Peace.

Can’t find a subtitled trailer for some reason but to be honest you’ll get the gist of it:

Based on the third of three short stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s novel of the same name, Asleep (白河夜船, Shirakawayofune) is an apt name for this tale of grief and listlessness. Starring actress of the moment Sakura Ando, the film proves that little has changed since the release of the book in 1989 when it comes to young lives disrupted by a traumatic event. Slow and meandering, Asleep’s gentle pace may frustrate some but its melancholic poetry is sure to leave its mark.

Based on the third of three short stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s novel of the same name, Asleep (白河夜船, Shirakawayofune) is an apt name for this tale of grief and listlessness. Starring actress of the moment Sakura Ando, the film proves that little has changed since the release of the book in 1989 when it comes to young lives disrupted by a traumatic event. Slow and meandering, Asleep’s gentle pace may frustrate some but its melancholic poetry is sure to leave its mark.

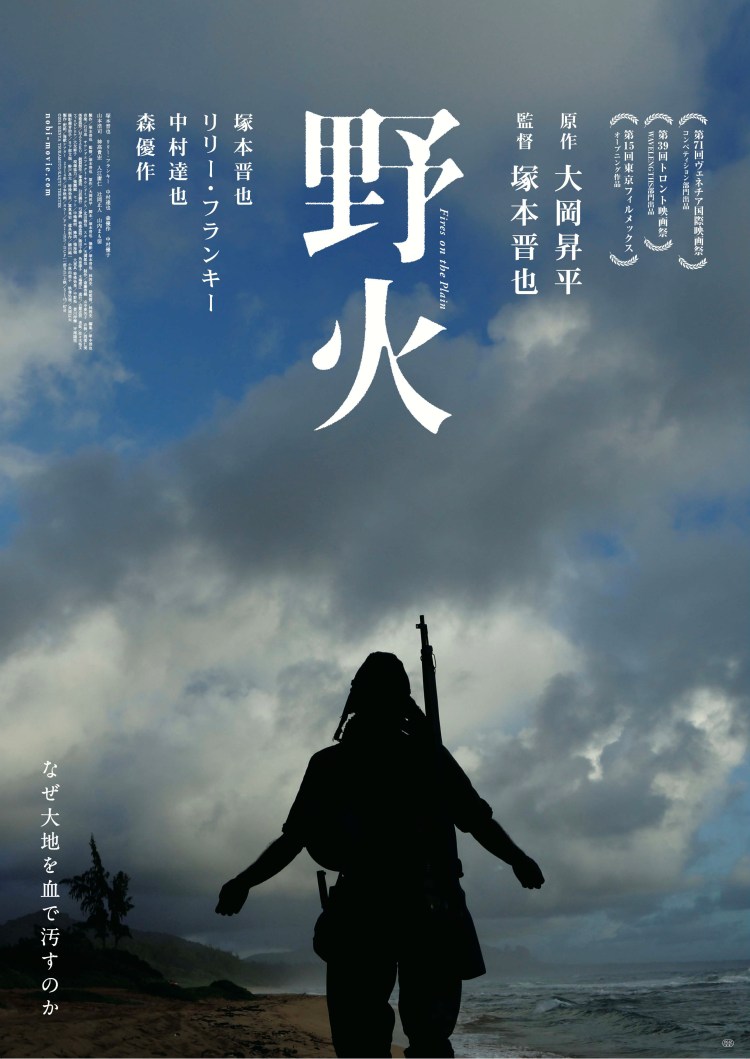

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by

Shinya Tsukamoto is back with another characteristically visceral look at the dark sides of human nature in his latest feature length effort, Fires on the Plain (野火, Nobi). Another take on the classic, autobiographically inspired novel of the same name by Shohei Ooka (previously adapted by