The youth movie has long held a special place in Japanese cinema but it would be fair to say that the fire has gone out of late, modern youth dramas are generally sad rather than angry. Daigo Matsui was in an enraged mood when he brought us Japanese Girls Never Die – a chronicle of female elision in an intensely misogynistic society. Now he brings his camera down a little to take a look at the incendiary play by boundary pushing British playwright Simon Stephens, Morning, through the eyes of real teenagers as their own hopes and dreams are suddenly pulled away from them by an act of “unfairness” which is perfectly typical of the treacherous adult world obsessed with rationality and not at all interested in their feelings.

The youth movie has long held a special place in Japanese cinema but it would be fair to say that the fire has gone out of late, modern youth dramas are generally sad rather than angry. Daigo Matsui was in an enraged mood when he brought us Japanese Girls Never Die – a chronicle of female elision in an intensely misogynistic society. Now he brings his camera down a little to take a look at the incendiary play by boundary pushing British playwright Simon Stephens, Morning, through the eyes of real teenagers as their own hopes and dreams are suddenly pulled away from them by an act of “unfairness” which is perfectly typical of the treacherous adult world obsessed with rationality and not at all interested in their feelings.

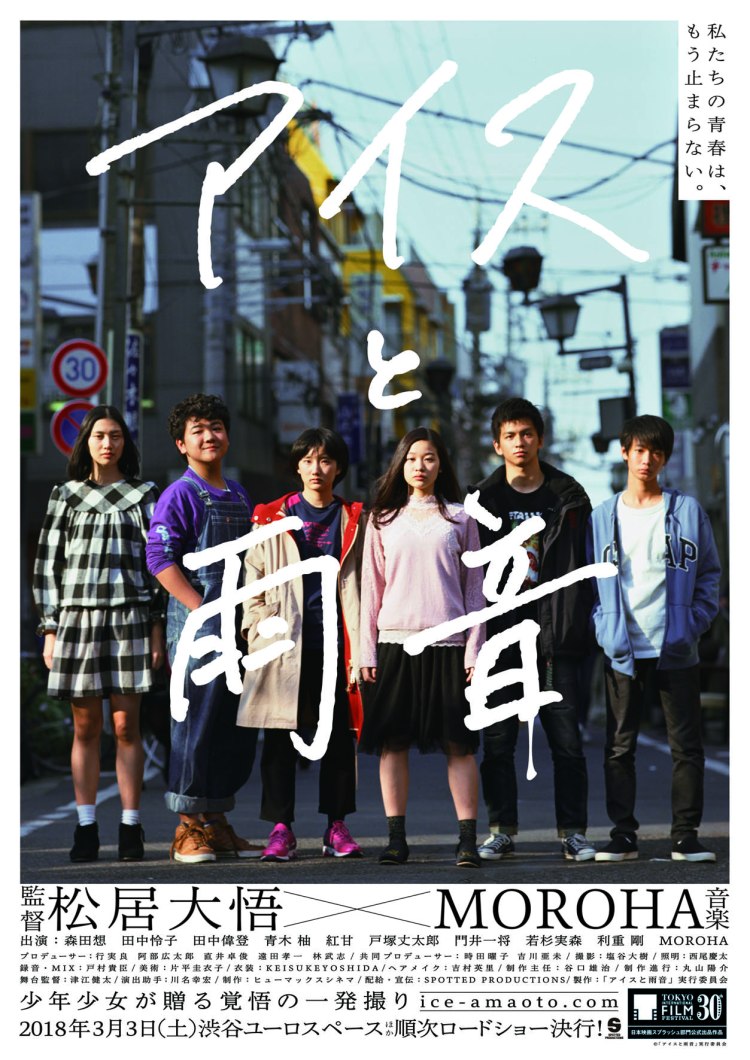

Shot entirely in one take, Ice Cream and the Sound of Raindrops (アイスと雨音, Ice to Amaoto) masterfully condenses the one month rehearsal period of the play into a mere 70 minutes through dreamlike time segues, neatly swapping aspect ratios as the “play” takes over from “real life”. Stephens’ play, set at the end of summer – the same time as the play is being rehearsed and was scheduled to be performed, is a coming of age tale in which its small town heroine attempts to deal with the impending departure of her best friend for university by embracing the “freedoms” of youth only to discover that not all transgressions are cost free.

In a bid for “realism” the play’s director, played by Matsui himself, has cast real local teens by means of an open audition, but times are tough for the arts. With no “names” in the cast, ticket sales are slow. The producers have decided to pull the production and cut their losses ahead of time. The youngsters are obviously upset. This was, after all, their big chance and they’ve worked hard only to be told that all their efforts are worthless because they just don’t have “it”. No one cares about their feelings, no one cares about their wasted time, no one cares about them.

The actors and actresses play characters with their real names, slipping into and out of the theatrical world with little warning until the two begin to blend almost seamlessly and it becomes impossible to tell which level of theatricality best represents the teens’ inner lives. The “play” is also scored by a kind of Greek chorus in the form of a slightly older rapper/performance poet who offers a more direct commentary on the general feelings of hopelessness which have begun to plague the young cast who know they will be emerging into a world with few possibilities in which they will be expected to abandon their youthful dreams for an idea of conventional success which is destined to remain far out of their reach.

The cutesy title, Ice Cream and the Sound of Raindrops, hints at another kind of youth story – the melancholy journey into nostalgia as an older protagonist looks back on a beautiful summer many years ago spent with friends who perhaps are no longer around. Matsui’s film has some of that too, though his protagonists are younger. The teens almost eulogise themselves, telling their story as if it’s already over, walking like ghosts through halls of memory. They’re sad, but they’re angry too and they don’t understand why their platform has been so arbitrarily removed just as they were preparing their voices to be heard.

If youth wants the stage it will have to take it by force. Sick of being blamed, of being told that their failures are all lack of talent rather than luck, the kids make themselves heard even if they do so through a veil. Daigo Matsui gives them back their stage, enriching it with his own artifice in the thrillingly complex choreography of his oscillating one take conceit. Anchored by a standout performance from leading lady Kokoro Morita on whom many of the transitions depend, Ice Cream and the Sound of Raindrops returns the youth film to its previous intensity with a rebel yell from the disenfranchised next generation who once again find themselves at odds with the society their parents’ have created and see no place for themselves within it which accords with their own sense of personal integrity.

Screened at Nippon Connection 2018.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Based on the third of three short stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s novel of the same name, Asleep (白河夜船, Shirakawayofune) is an apt name for this tale of grief and listlessness. Starring actress of the moment Sakura Ando, the film proves that little has changed since the release of the book in 1989 when it comes to young lives disrupted by a traumatic event. Slow and meandering, Asleep’s gentle pace may frustrate some but its melancholic poetry is sure to leave its mark.

Based on the third of three short stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s novel of the same name, Asleep (白河夜船, Shirakawayofune) is an apt name for this tale of grief and listlessness. Starring actress of the moment Sakura Ando, the film proves that little has changed since the release of the book in 1989 when it comes to young lives disrupted by a traumatic event. Slow and meandering, Asleep’s gentle pace may frustrate some but its melancholic poetry is sure to leave its mark.