There’s a moment in Amanda Nell Eu’s Tiger Stripes in which a teacher writes a sentence in English on the board for the students to fill in the blanks. “The father ___ to work,” one reads. Another, “The mother ___ at home.” It’s within these blanks that the girls live their lives, contained by rigidly held patriarchal norms supported by a religious environment that turns resistance into heresy, something demonic and evil that must be rooted out so the afflicted individual can be returned to society without their parents being ostracised.

A bright and talented student, Zaffan (Zafreen Zairizal) is shown to flaunt these rules by wearing a bra and commandeering the toilets to record tiktok dance videos with the help of her friends Mariam (Piqa) and the more conservative Farah (Deena Ezral). Perhaps the most transgressive thing about them is that she’s removed her hijab and in fact much of her clothing, defiantly assuring herself with a cheekiness that seems almost naive. After getting her school uniform wet in a local pond, she cheerfully runs home hair exposed in only her smalls. Her father barely bats an eyelid, but her mother is incensed. Somewhat counter productively, she drags her outside and shouts at her in front of all the neighbours about bringing shame on their family.

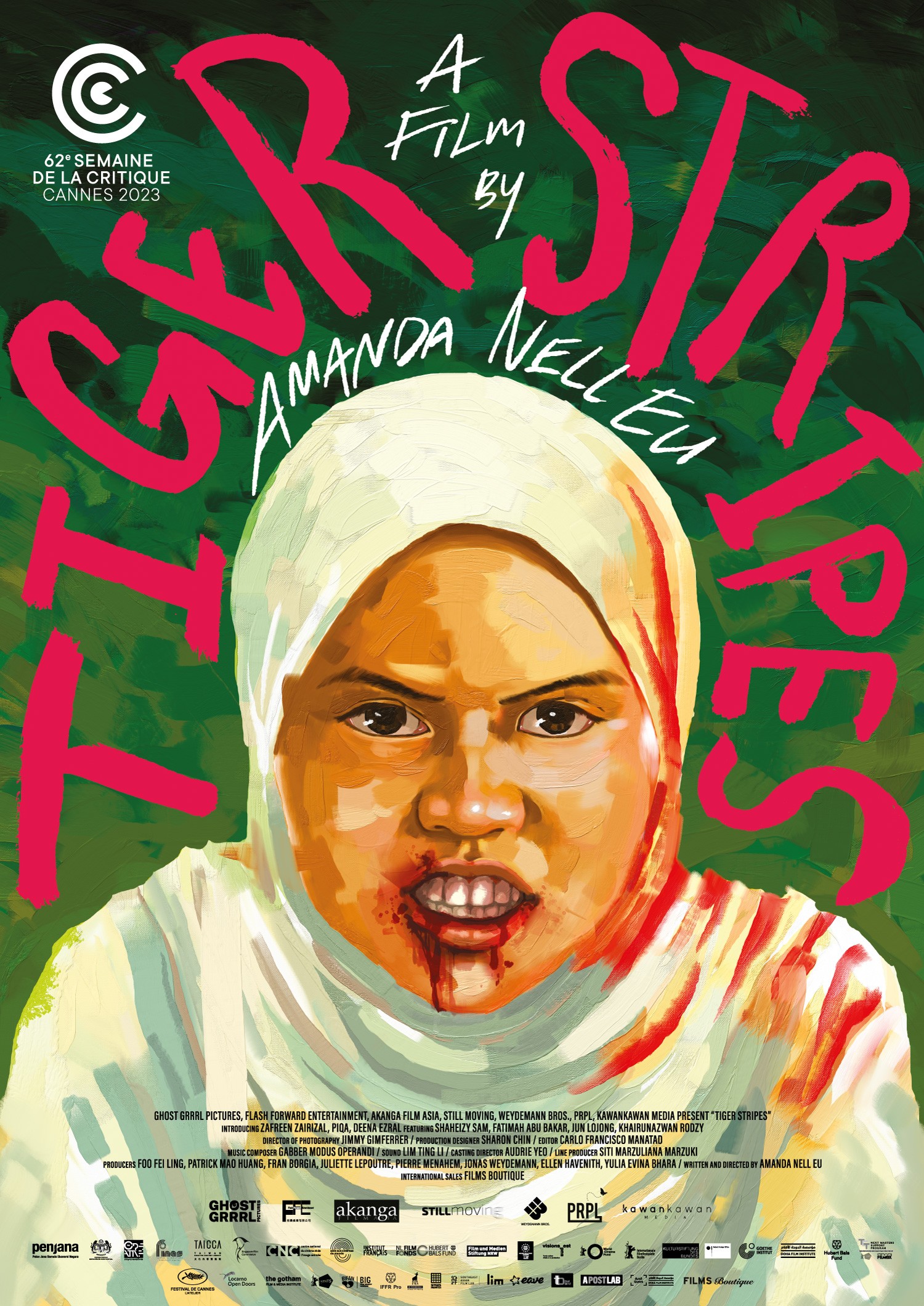

Time and again, it’s other women that cause Zaffan the most trouble. After her classmates discover that she’s got her period and is therefore a woman, they beat her up and call her names suggesting that she’s unclean and no longer wanting to associate with her. It doesn’t help that her new status is known to all because girls on their period cannot participate in some of the religious practices at the school which similarly reinforce the idea that menstruation is a pollutant and womanhood itself is toxic. It’s indeed womanhood which been activated in Zaffan along with a natural desire to resist her oppression and be who she is. She begins to undergo a transformation that even she barely understands, snapping and snarling those who challenge her while otherwise catching and eating wild animals which she tears apart with her teeth.

The girls tell each other a story of a woman, Ina, who apparently went feral and escaped to live in the forest. They tell it as a cautionary tale, but Zaffan begins to see and identify with Ina who has found a kind of natural freedom outside of the oppressive patriarchal social codes of the contemporary society. Yet it’s precisely this freedom that must tempered ad women kept in their place. The school later calls in some kind of spiritualist, Dr. Rahim (Shaheizy Sam ), who pedals snake oil treatments and claims to be able to exorcise the young women who have similarly come down with shakes and shivers in the wake of Zaffan’s metamorphosis. Earlier on, Zaffan had seen a wild tiger filmed by a man who walked slowly behind it, menacing but unwilling to engage. Her friends tell her they probably mean to kill it, but there’s also an ineffectuality in this male timidity that is essentially afraid of an independent woman. Having transformed herself into a tigress, Zaffan too is followed by a crowd of men but all they do is stare at her back.

Meanwhile, in the background her teachers make ironic comics that the students won’t amount to anything while the Malay pupils seemingly trail behind their Chinese classmates. Zaffan becomes the embodiment of monstrous femininity, a dangerous and transgressive womanhood that rejects all of the constraints placed upon it. Though she does not understand what is happening to her and is hurt that her former friends, still on the other side of adolescence, now view her as something other and unpleasant, Zaffan longs for the freedom of the forest and to dance to her heart’s content no longer willing to submit herself to the strictures of the patriarchal society. Her rebellion earns its followers among girls of her age, themselves longing for freedom but too afraid to ask for it. Tinged with supernatural dread, the film nevertheless presents Zaffan’s progress as a gradual liberation found in the natural world, nature red in tooth and claw but alive and unconstrained as free as a tigress in a world without man.

Tiger Stripes is in UK cinemas now courtesy of Modern Films.

UK trailer (English subtitles)