A naive young woman’s path from besotted teen to tortured yet masterful courtesan amid the colonial realities of pre-war Hong Kong is elegantly charted in Ann Hui’s stately adaptation of the novel by Eileen Chang, Love After Love (第一炉香, Dì yī lú xiāng). A slow-burn romantic tragedy, Hui’s floating drama at once reflects a sense of hopeless rootlessness and the ruinous intensity of a one-sided love but also the transgressive possibilities for freedom and independence in the rejection of traditional patriarchal social codes.

Displaced from her native Shanghai by ongoing political tension, Weilong (Ma Sichun), the daughter of a once noble house, finds herself impoverished and left with the choice either of accompanying her family in returning to the Mainland where she will be set back a year in completing her studies or remaining behind alone in Hong Kong to graduate high school. Unable to support herself, she decides to turn to an estranged aunt she barely knows, throwing herself on her mercy and asking to be taken in even while knowing of the animosity which exists between her father and his sister. That would be because her aunt, Madame Liang (Faye Yu), turned down all the suitors her family found for her and chose instead to become the mistress of a wealthy man. He now having died, Madame Liang has inherited a sizeable fortune including a European-style mansion where she hosts society parties and enjoys a hedonistic lifestyle which has earned her a reputation as a seducer of young men.

On her introduction to this world, one of the maids uncharitably describes Weilong’s entrance as like that of a new girl in a brothel and there is indeed something of that in her new role in the household, dangled like a bauble in front of Madame Liang’s collection of wealthy male associates, though Madame Liang apparently intends her only as decoration rather than gift. Tensions come to the fore as Weilong develops a fondness for a dashing young man, George (Edward Peng Yu-Yan), the mixed ethnicity son of coterie member Sir Cheng (Paul Chun), previously eyed by Madame Liang who understands much better than her naive niece that men like George are dangerous in their destabilising faithlessness. For Madame Liang, so perfectly in control, George may be manageable but as she later tells Weilong, unwisely goading her that her life of comfort is a failure because she will never find love, the only danger that exists to her is in unequal affection a prophecy that will in a sense come to pass in Weilong’s single-minded obsession to possess the heart of George.

Weilong may describe Madame Liang’s lifestyle as ridiculous, yet as she points out her transgressive sexuality is also currency that permits the opulence and luxury in which she lives. Seduced by this world as much as by George, Weilong disapproves but admits that she is no longer the naive girl who arrived even if she also dislikes this new version of herself, considering a return to Shanghai and a possible reset to become someone else again presumably more in line with contemporary notions of social proprietary. She can’t deny that Madame Liang’s rejection of the patriarchal institution of marriage has granted her an unusual degree of independence otherwise unavailable in the contemporary society. She herself faces a choice in approaching the end of her high school days, either progressing to higher education, seeking work, or getting married naively insisting to Madame Liang that she will earn money in order to support George and his lavish lifestyle even as she advises her to enact a plot of romance as revenge.

While Weilong’s discarded suitor benefits financially in becoming Madame Liang’s lover, she sponsoring his study abroad, Weilong again attempts to reverse traditional gender roles by trapping George as a kind of trophy husband. He had repeatedly told her he wasn’t the marrying kind, in part because of his insatiable sexual desire and perpetual loneliness in having lost his mother young, yet also because of his father’s perfectly acceptable yet socially destructive romantic history which includes several concubines and illegitimate children meaning there will be little in the way of inheritance. If he married, he’d need to marry well but Weilong’s family is impoverished and she has only her connection with Madame Liang to leverage. As she’d warned her it would be, the relationship between them will always be unhappy, Weilong winning a symbolic victory in coercing George towards marriage but unable to accept the limits of her control while he, paradoxically, is emotionally honest only with her but she can only see this as a slight as if he is so indifferent towards her that she is not worth lying to.

As Weilong gradually morphs into her aunt, George’s sexually liberated sister Kitty lands on a different path later becoming a nun. The three women attempt to muster all of the advantages afforded to them under an oppressive patriarchal system but none perhaps find true happiness. It might be tempting to read a subversive comment on the nature of colonialism in the various frustrated love affairs and persistent sense of rootlessness, Hui’s drama is at heart a romantic tragedy in which two people become locked in a torturous relationship because they cannot understand each other. Their very idea of love is different. Doyle’s floating camera perfectly captures the fleeting opulence of this unreal society itself lingering on an abyss as the lovers continue to dance around each other looking perhaps for the love after love in immaterial comfort.

Trailer (English subtitles)

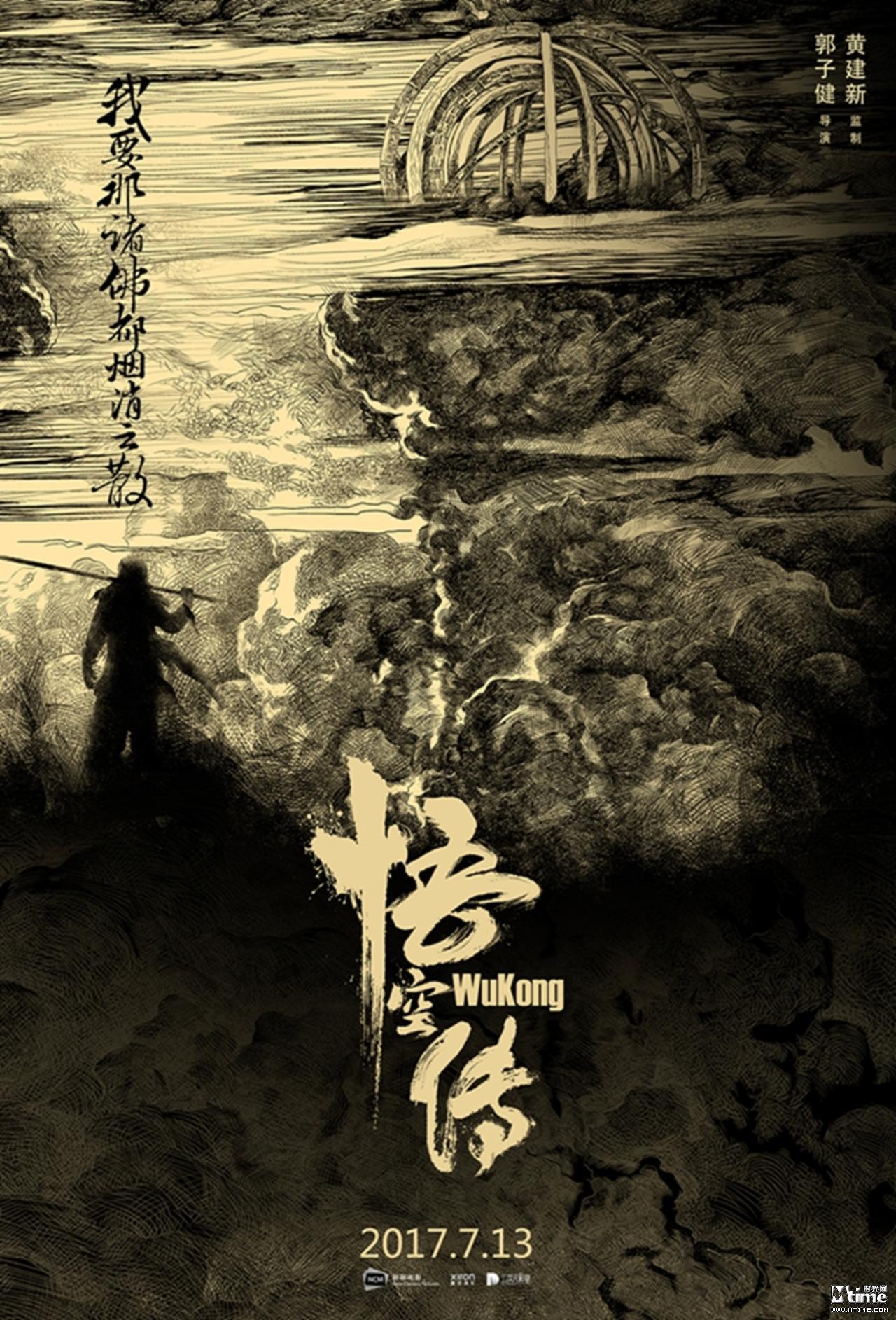

As it stands, contemporary Chinese cinema is veering dangerously close to Monkey King fatigue. Stephen Chow brought his particular sensibilities to the classic Journey to the West before Donnie Yen put on a monkey suit for

As it stands, contemporary Chinese cinema is veering dangerously close to Monkey King fatigue. Stephen Chow brought his particular sensibilities to the classic Journey to the West before Donnie Yen put on a monkey suit for