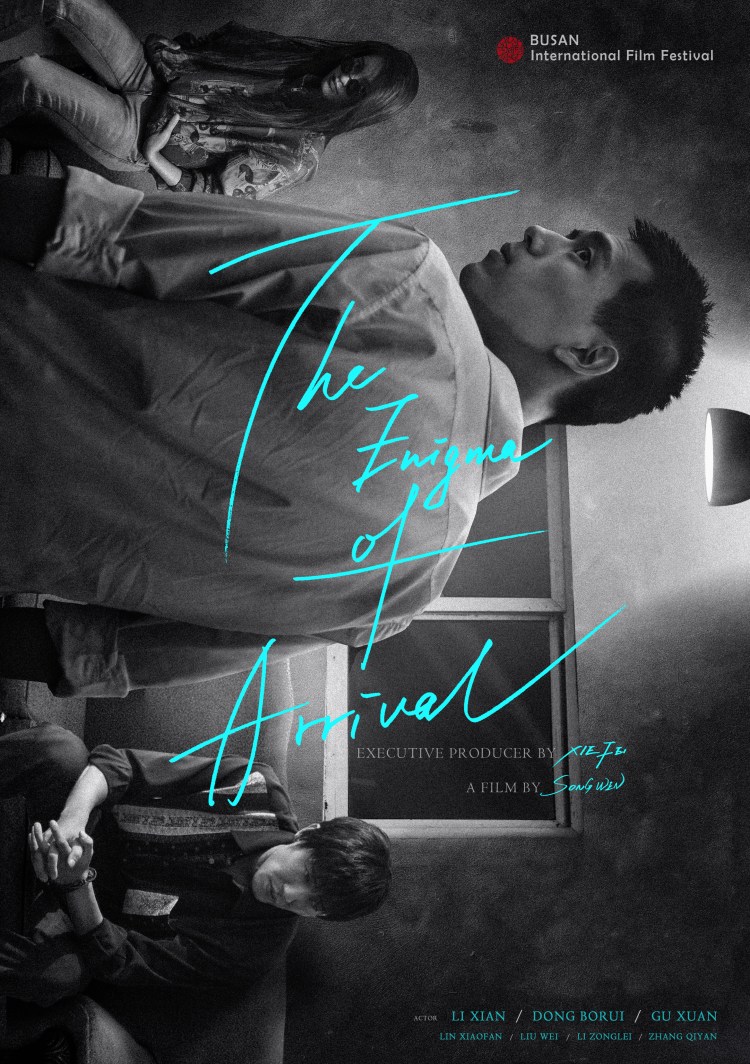

Chinese cinema has always had a fondness for melancholy nostalgia. Perhaps its natural enough to romanticise one’s youth and long for a simpler time of possibility, though that same desire for “innocence” has often been read as a rebuke on the “soulless” modern economy and critique of Westernising individualism of a China some feel has lost its way since the economic reforms of the ‘80s and beyond. Song Wen’s The Enigma of Arrival (抵达之谜, Dǐdá Zhī Mí), seemingly borrowing a title from the novel by VS Naipaul, seems more straightforwardly personal in its universality as it locates a single fracturing point in the lives of a collection of young people forced apart yet eternally connected by tragedy and disappointment.

Chinese cinema has always had a fondness for melancholy nostalgia. Perhaps its natural enough to romanticise one’s youth and long for a simpler time of possibility, though that same desire for “innocence” has often been read as a rebuke on the “soulless” modern economy and critique of Westernising individualism of a China some feel has lost its way since the economic reforms of the ‘80s and beyond. Song Wen’s The Enigma of Arrival (抵达之谜, Dǐdá Zhī Mí), seemingly borrowing a title from the novel by VS Naipaul, seems more straightforwardly personal in its universality as it locates a single fracturing point in the lives of a collection of young people forced apart yet eternally connected by tragedy and disappointment.

Song begins in the present day with his 40-ish narrator, San Pi (Liu Wei), who tells us that he is looking forward to reuniting with his old friends with whom he has largely lost touch. Falling into a reverie, he takes us back to their harbourside hometown some 15 years or so previously when he used to hang out with three friends from school – Feng Yuan (Dong Borui), Xiaolong (Li Xian), and Da Si (Lin Xiaofan). Young men, they spent their time watching “cool” Hong Kong movies like Days of Being Wild and A Better Tomorrow, which were always followed by a blue movie watched incongruously in public. The trouble starts when the guys meet local beauty Dongdong (Gu Xuan) and are all instantly smitten. Hoping to get themselves a more impressive motorbike, they make a fateful decision to steal some diesel and sell it on, only the fuel they steal belongs to gangsters which lands them in a world of trouble they are ill-equipped to deal with despite their adolescent male posturing. Dongdong disappears without trace leaving the guys wounded and confused.

As San Pi tells us in his opening monologue, things are not always as they seem, “Life is floating between fiction and reality”. It’s a particularly apt comment from him because, as we later find out, he was present only for the single climactic events not for the ones which preceded and followed them. He didn’t go with the guys when they, mistakenly, tagged along with Dongdong to an athletics tournament to which she only intended to invite Xiaolong, and as he left soon after Dongdong disappeared his memories of those times are not first hand. He invites us to assume that each of the men has their own narrative which necessarily places themselves at the centre and offers a flattering portrait of their actions which attempts to absolve them of guilt for whatever they did or did not do to lose Dongdong.

A case in point, though it seems that Dongdong favoured Xiaolong who has spent the remainder of his life pining for her, Fang Yuan always thought she fancied him while Da Si was technically dating her friend Xiaomei (Zhang Qiyuan) but seems to have developed some kind of protective sympathy towards her which may have an edge of puritanical resentment. San Pi is the only one who does not seem to have engaged in sad romance, a perpetual outsider looking on from the edges. That might be why he seems to be the one eulogising their friendship, less hung up on what happened to Dongdong than on the effect it had on the later course of his life and that of his friends. Reuniting in a Japanese-style onsen, an ironic reminder of their youthful dreams to see Japan, he wonders if they might return to their teenage intimacy but discovers that youthful innocence cannot be reclaimed once lost, some secrets must stay secret, and some betrayals are too much to bear. They will never go to Japan together, or even catch a movie in a rundown theatre. It would be embarrassing; the moment has passed.

Song frames his tale in a mix of hazy images and black and white, neatly symbolising the patchwork quality of narrative assembled from memory and wishful thinking, coloured by a single perspective that lacks the composite whole of accepting the reality of others’ perceptions. In contrast to the longing for the old China that marks many a youth drama, Song’s young guys yearn for the world – they worship Hong Kong tough guys, listen to Western music, and dream of seeing Japan, but their present life is one of settled middle-aged disappointment marked by the unresolved tragedy of their pasts which both binds them together and forces them apart. “No one is flawless” Xiaolong is reminded, but somehow that only makes it worse. A melancholy ode to ruined friendship and the nostalgia of bygone adolescent possibility, Enigma of Arrival is a suitably abstract effort from the founder of the XINING FIRST International Film Festival and signals a bold new voice on the Chinese indie scene.

The Enigma of Arrival screens in Chicago on Sept. 19 as part of the ninth season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema where director Song Wen will be present for an intro and Q&A.

Original trailer (English subtitles)