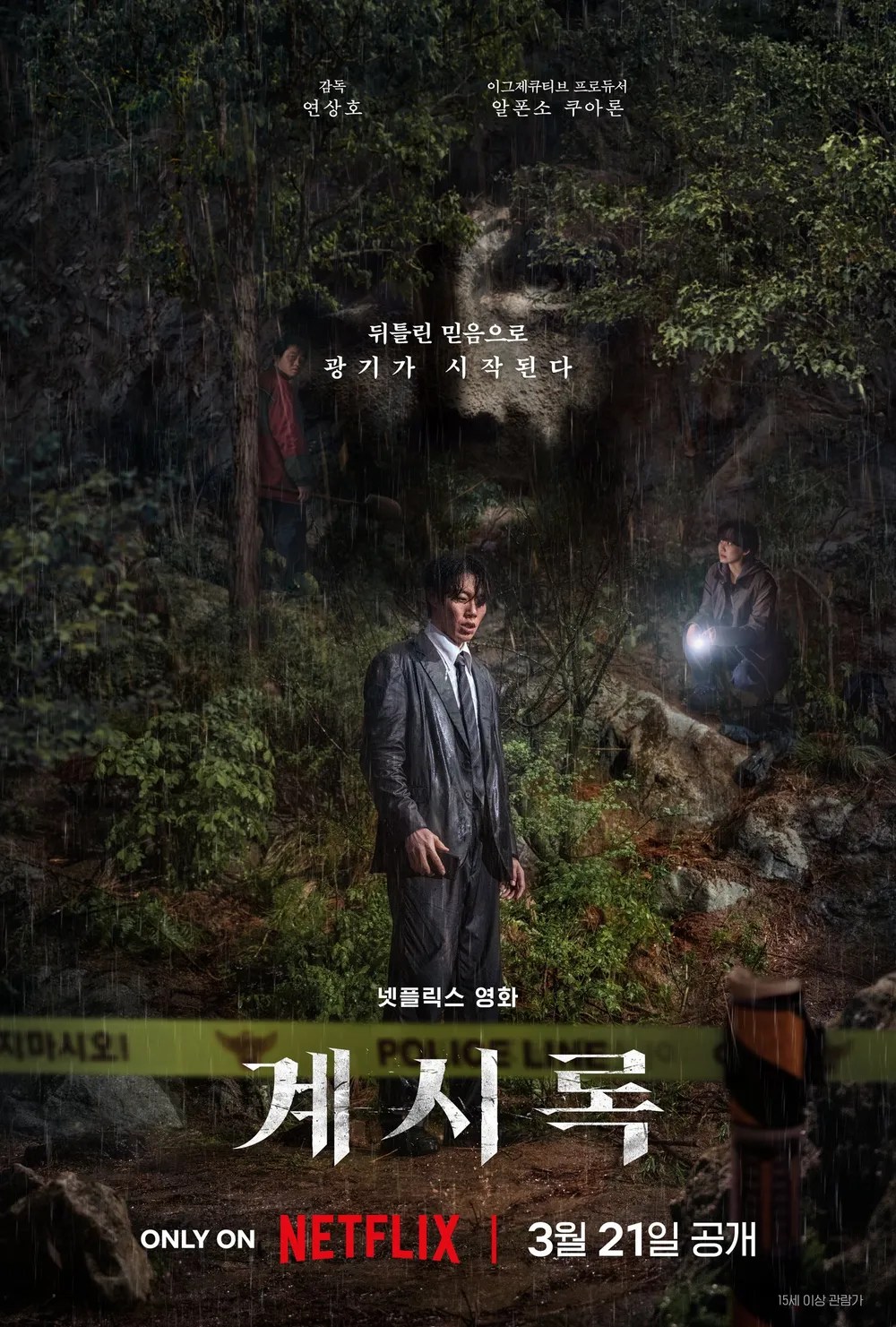

A put upon pastor’s life begins to spiral out of control when he comes to suspect a recently released sex offender has kidnapped his child in Yeon Sang-ho’s grim spiritual drama, Revelations (계시록, Gyesirok). Less about the crime at its centre, the film is more an exploration of our intense desire to justify our actions and remake the world in a way that makes sense to us while refusing to see or accept the reality of others.

Min-chan (Ryu Jun-yeol) runs a small evangelical church that is part of a larger religious organisation and like any other ambitious employee is hoping for advancement. With the area undergoing redevelopment, a larger church is to be built and Min-chan’s wife Si-yeong (Moon Joo-yeon) comes to the conclusion that his mentor Pastor Jung gave him this smaller church to build a congregation in preparation for heading up this larger one. But Jung rather insensitively asks him if he can think of anyone to run it while suggesting that ideally he’d prefer to give it to his son, Hwan-su, though Hwan-su doesn’t feel ready and thinks Min-chan would be a better fit. Min-chan consoles himself by repeating the pastor’s words that God will show them the right person for the job and is secretly heartened when Hwan-su is out of the running due to the exposure of an extra-marital affair with a parishioner. But on the other hand, he’s recently discovered his wife has been having an affair with her personal trainer, which means he wouldn’t get the job either if anyone found out.

As such, he’s under an intense amount of pressure and increasingly dependent on revelations he believes are from God. When Yang-rae (Shin Min-jae) walks into his church, Min-chan is intent on recruiting him but is unnerved by his ankle bracelet. When his own child goes temporarily missing, he becomes convinced that Yang-rae has taken them, especially when he sees Yang-rae loading up his van with shovels. Though this is an example of Min-chan’s latent prejudice and a contradiction in his religiosity given that he has no idea what Yang-rae might have done and is uninterested in helping him only in increasing the numbers of his congregation, it turns out that Yang-rae has taken another child from among his parishioners. Having had an altercation with Yang-rae and attempting to cover up his crime, Min-chan pretty much forgets about A-yeong (Kim Bo-min) and believes he has received a revelation that she’s dead and it’s his mission to purge the evil of kidnappers by killing Yang-rae, coming over all fire and brimstone and ignoring Yang-rae when he points out they’ll never find A-yeong if he dies.

For Min-chan, Yang-rae has become a faceless figure of evil in a similar way he has for traumatised policewoman Yeon-hee (Shin Hyun-been) who is haunted by the ghost of her sister who took her own life after being kidnapped and tortured by Yang-rae. A psychiatrist she meets explains to her that the ghost isn’t real but only a manifestation of the guilt she feels for not being able to save her sister. Her desire to save A-yeong is also a means of making peace with the traumatic past, but even she is caught between the desire for revenge and that of finding her in being at least tempted to pull the trigger and kill Yong-rae herself. She had also been further harmed psychologically by the fact that Yong-rae got a reduced sentence on the grounds of the horrific childhood abuse he’d suffered at the hands of his step-father. But it’s only by acknowledging that he wasn’t a faceless evil but a real person with his own feelings and trauma that she can come to understand him and put the clues together to find A-yeong.

As the psychiatrist says, Min-chan’s God, Yeon-hee’s ghost, and Yang-rae’s one-eyed monster are all the same thing. They’re trying to overcome the reality that most tragedies in life are caused by things we can’t control. Placed into a police cell, Min-chan has a large square window that floods the room with light, but also a large smudge in the wall that looks sort of like Jesus. He begins scrubbing at it, trying to clarify the image, but it just becomes muddier and could just as easily be a demon rather than God, leaving him finally uncertain as to from whom he was receiving his “revelations”, be they from God, the devil, or just his own confused mind, while dealing with the stress of having his masculinity and career progress undermined in being cheated on by his wife and passed over by his mentor. While Yeon-hui has laid her ghosts to rest, all Min-chan is left with is uncertainty.

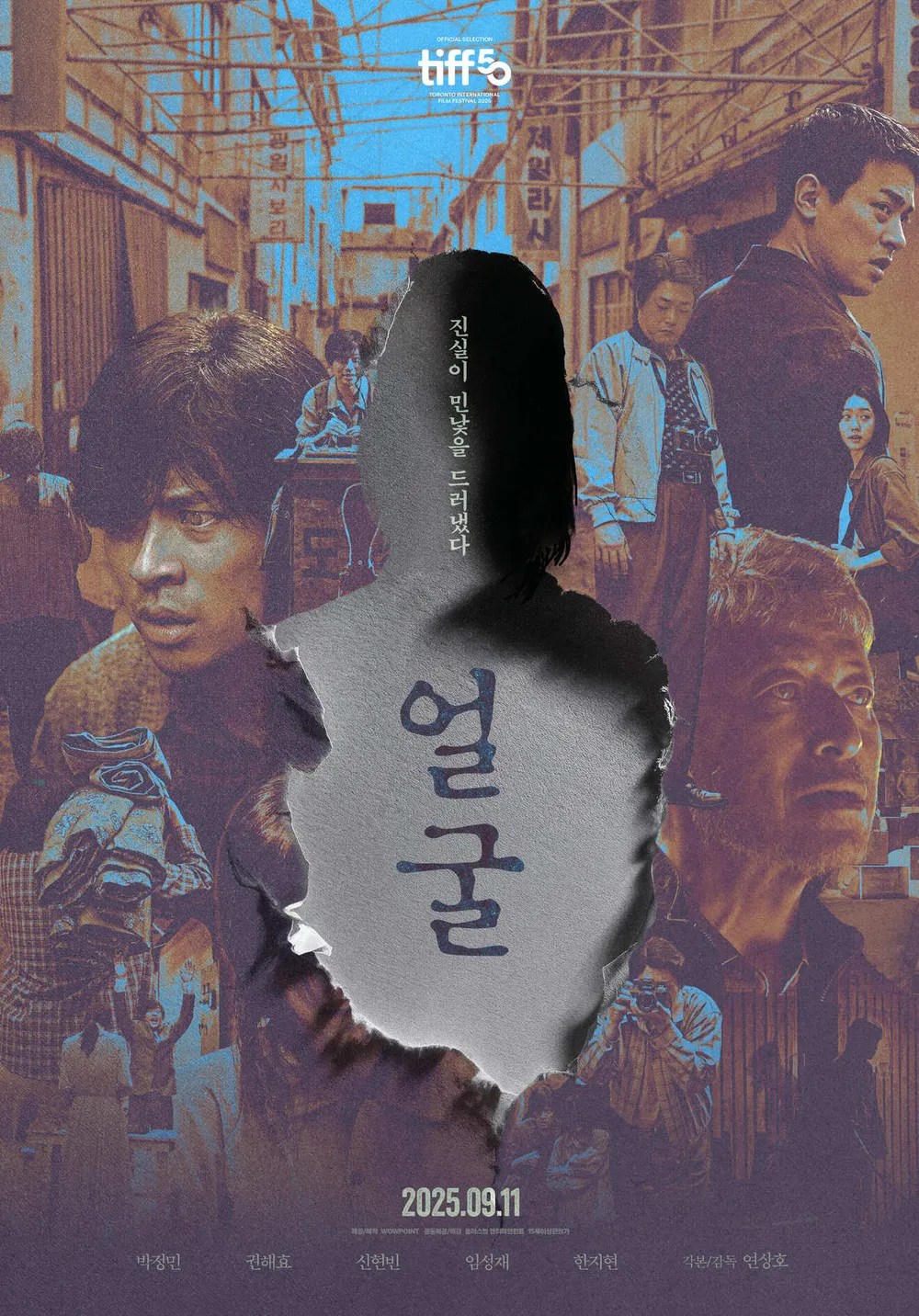

Trailer (English subtitles)