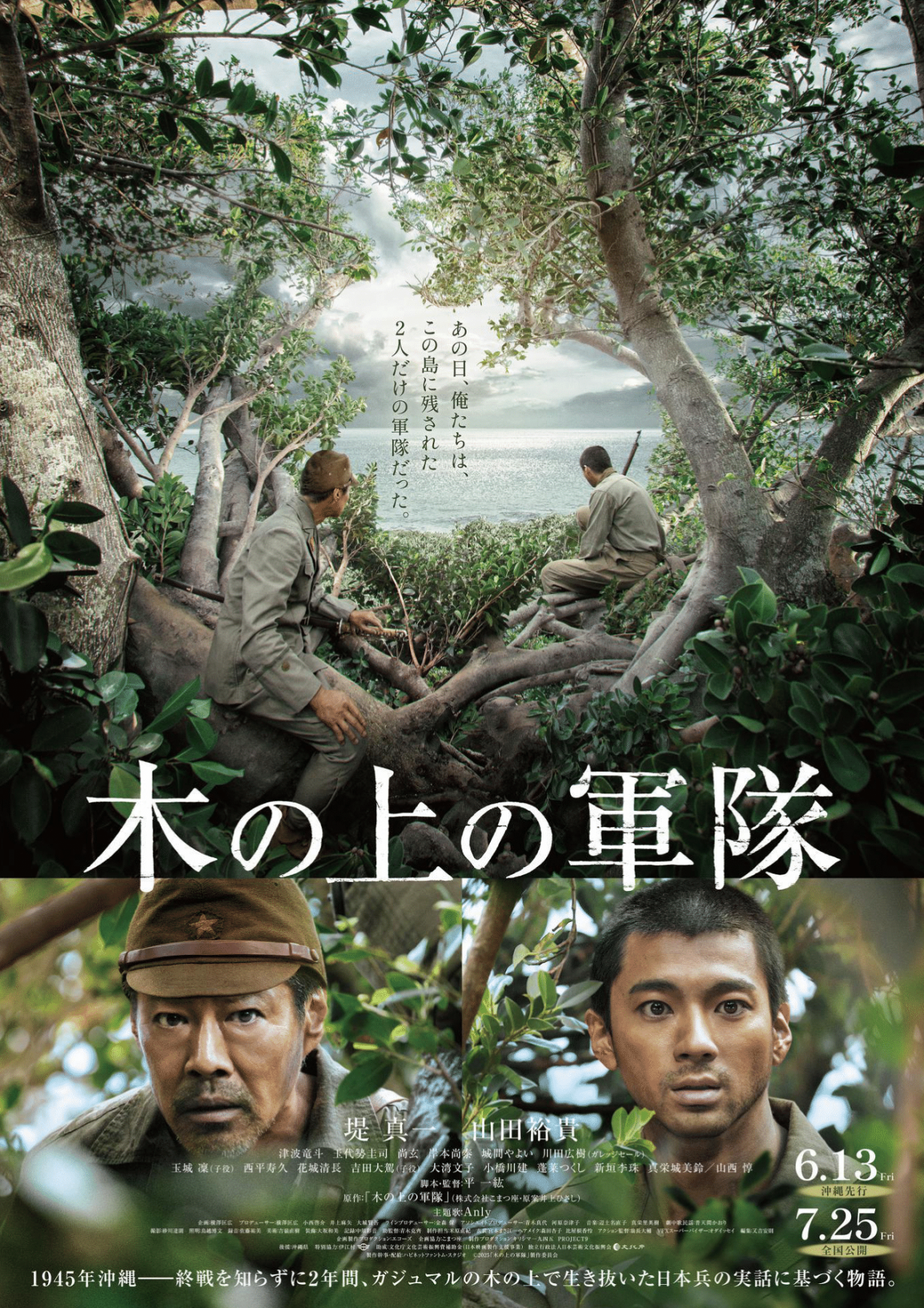

Based on an unfinished play by Hisashi Inoue, Kazuhiro Taira’s Army on the Tree (木の上の軍隊, Ki no Ue no Guntai) confronts the absurdity of war by marooning its heroes in a banyan tree far above the conflict but also increasing unwilling to come down and face an uncertain reality. Instead, they remain in a kind of limbo, trapped somewhere between life and death in continuing to fight their war in their own way while unbeknownst to them, the wider world moves on.

In any case, this “army of two” is comprised of very different men with a complicated and ever-shifting dynamic. Lieutenant Yamashita (Shinichi Tsutsumi) is a loyal militarist from Miyazaki on the mainland, while private Agena (Yuki Yamada) is a local who has never left the Okinawan island where his family were once farmers, until the Japanese army requisitioned their land. The truth is that Japan is a coloniser here, too, and there’s an awkwardness involved in the way they see the islanders as both Japanese and not. While discussing the building of a new air base Yamashita describes as the envy of the Orient, one of the other officers suggests they will simply use “the locals” in suicide attacks as if their lives are completely disposable and not of equal value to those of the mainland soldiers, while simultaneously suggesting they belong entirely to the empire for the commanding officers to use as they see fit. They’ve been training the civilian villagers in local defence using spears to attack straw models labelled “Churchill” and “Eisenhower”, but when one older man jokes about smearing his with excrement so the enemy might have a better chance of dying of infection, Yamashita beats him about the head for what seems like an eternity.

It’s Yamashita who seems to cling fiercely to militarist ideology and his loyalty to the emperor, even if there’s an obvious conflict in the fact that he’s “run away” to hide in this tree with Agena while the rest of his men are dead. This also gives him an additional psychological reason to want to stay up there so that he won’t have to face his guilt and shame in the defeat and having survived it along with having allowed all of his men but one to die. Trapped there together, the two men have no reason to believe that anything has changed and think the battle is still ongoing with American soldiers patrolling the forest. They attempt to survive foraging for food and water, drinking from a trough into which a dead body has fallen while Yamashita at first firmly rejects the idea of eating tinned food left behind by the Americans, describing it as “enemy food” and the eating of it as an act of treachery. Agena is not so foolish and finally gets Yamashita to eat some and avoid starvation by tipping some of it into an old Japanese army ration tin.

But as much as Yamashita is in charge by virtue of military hierarchy, he’s also a stranger here while Agena is intimately familiar with the terrain. He has a much better idea of knowing how to survive in the forest and which plants and insects are okay to eat. The truth is that the army had confiscated all this land to turn it into an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” which the local recruits had to build with their own hands. Once the situation deteriorates, they’re ordered to blow the whole thing up to prevent the Americans taking it over rendering their labour entirely pointless especially as their only goal is to slow the Americans down. They have no real prospect of stopping them or of surviving the assault. Meanwhile, as Agena points out, neither he nor the island will ever be the same again. His mother had lost her mind after their land was taken and his father failed to return from the war, while most of his friends are dead and the places he played as a child have taken on new meanings or perhaps no longer exist. The world before the war is lost to him, and he can’t ever go home again, unlike Yamashita who still has somewhere, and presumably also someone, to go back to.

Yamashita is not altogether appreciative of this fact as much as he comes to see Agena as a stand in for the son from whom he’d become estranged because of his hardline authoritarianism. Nevertheless, the bond that’s arisen between them does begin to reawaken his humanity and dissolve the rigidity of his ideology so that he is gradually able to accept the reality that Japan has lost the war, their battle is over, and it’s time to come down from the tree. Taira largely avoids judgement or falling into the trap of glorifying these men’s actions as soldiers who refused to give in, focussing instead on the absurdity of their position along with the literal and psychological dimensions of their purgatorial existence as they attempt to process how to move forward into an unknown world while still tormented by the old.

Army on the Tree screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Trailer (no subtitles)