When a body is discovered buried with a priceless set of shogi tiles, it unearths old truths in life of an aspiring player in Naoto Kumazawa’s sprawling mystery, The Final Piece (盤上の向日葵, Banjo no Himawari). In Japanese films about shogi, the game is often a maddening obsession that is forever out of reach. Hopefuls begin learning as children, sometimes to the exclusion of everything else, but there’s age cut off to turn pro and if you don’t make the grade by 26, you’re permanently relegated to the ranks of the amateur.

Junior policeman Sano (Mahiro Takasugi) was one such child and in some ways solving the crime is his final match. The thing is, he loves the game and admires Kamijo’s (Kentaro Sakaguchi) playing style along with the aspirational quality of his rise from nowhere not having trained at the shogi school and turning pro at the last minute to win a prestigious newcomer tournament. He’s hoping Kamijo will win his game against prodigious player Mibu (Ukon Onoe) with whom Kamijo’s fortunes are forever compared. Which is all to say, Sano really doesn’t want Kamijo to be the killer and is wary of accusing him prematurely knowing that to do so means he’ll be kicked out of professional shogi circles whether he turns out to be guilty or not.

Nevertheless, the more they dig into Kamijo’s past, a sad story begins to emerge that strongly contrasts with his present persona, a slightly cocky young man with a silly beard and smarmy manner. While Mibu seems to have been indulged and given every opportunity to hone his skills, Kamijo was a poor boy whose father had drink and gambling problems and was physically abusive towards him. His mother took her own life, leaving Kamijo to fend for himself with a paper round while his father occasionally threw coins at him and railed against anyone who questioned his parenting style. Good intentions can have negative consequences, the landlady at his father’s favourite bar remarks recalling how he went out and beat Kamijo for embarrassing him after another man told him he should be nicer to his son.

Toxic parental influence is the wall Kamijo’s trying to break in shogi. Aside from the man raising him, Kamijo finds another, more positive, paternal figure in a retired school teacher (Fumiyo Kohinata) who notices his interest in shogi and trains him in the game while he and his wife also give him clean clothes and a place to find refuge. But Kamijo can’t quite break free of his father’s hold much as he tries to force himself to be more like the school teacher. As an impoverished student he meets another man, the cool as ice yakuza-adjacent shogi gambler Tomyo (Ken Watanabe), who insists he’s going to show him the “real” shogi, but in reality is little different from his father if more supportive of his talent.

Kamijo finds himself torn between these three men in looking for his true self. Though he may tell himself he wants to be like the schoolteacher being good and helping people in need, he’s pulled towards the dark side by Tomyo and a desperate need for shogi which tries to suppress by living a nice, quiet life on a sunflower farm that reminds him of the happier parts of his childhood. There’s a cruel irony in the fact that the police case threatens to ruin to his shogi success at the moment of its fruition, even if it accompanies Kamijo’s own acceptance of his internal darkness and the way it interacts with his addiction to the game.

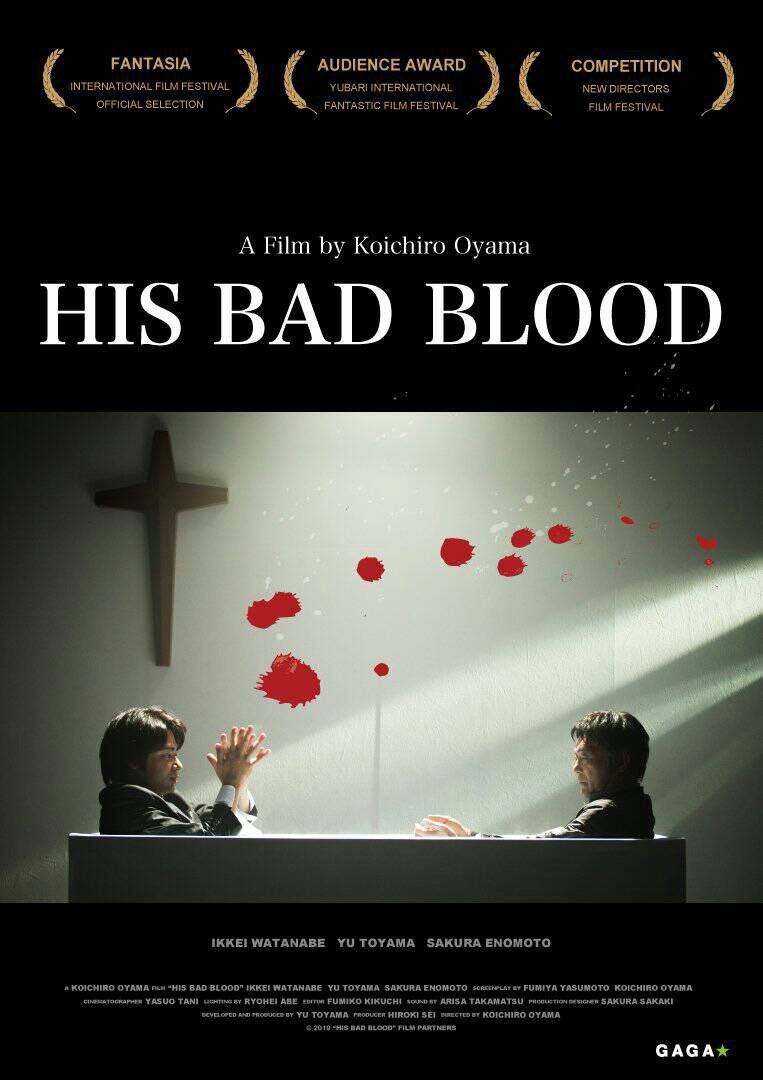

Tomyo’s own obsession may have ruined his life as he looks back over the town where he spent his happiest months with a woman he presumably lost because of his gambling and need for shogi glory even though he never turned professional and remained a forever marginalised presence as a gambler in shogi society. Unlocking the secrets of his past seems to give Kamijo permission to accept Tomyo’s paternal influence and along with it the darker side of shogi, but there’s something a little uncomfortable in the implication that he was always doomed on account of his “bad blood” aside from the toxic influences of his some of his father figures from the man who raised him and exploits him for money well into adulthood, and the ice cool gangster who taught him all the best moves the devil has to play along with a newfound desire for life that may soon be snuffed out.

The Final Piece screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.