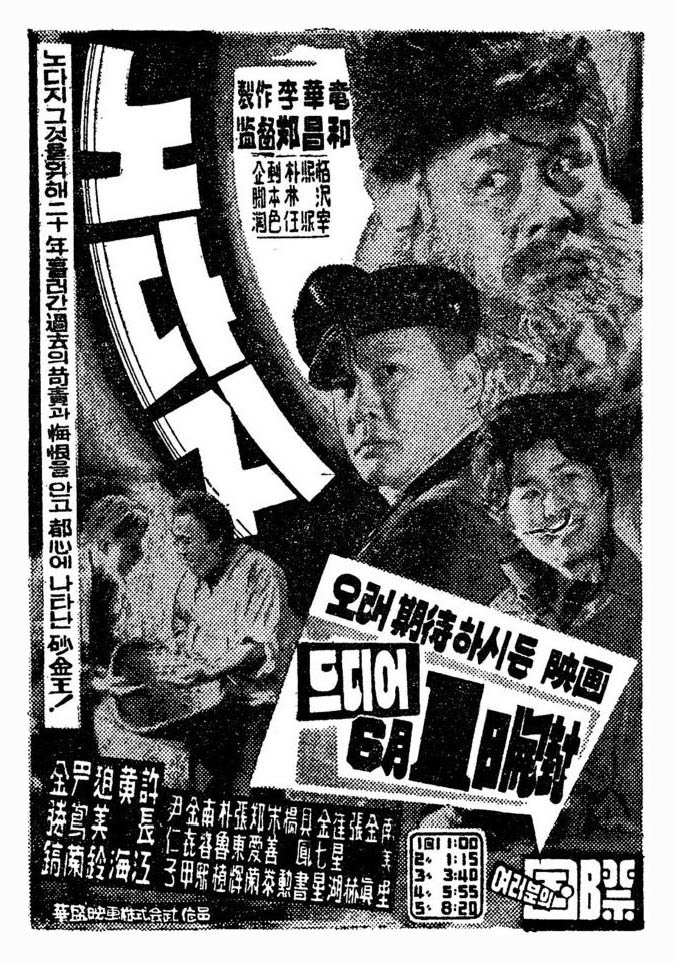

Chung Chang-wha is best remembered as a pioneer of Korean action cinema, eventually travelling to Hong Kong to direct martial arts movies with Shaw Brothers. 1961’s A Bonanza (노다지, Nodaji) arrives at a moment in which melodrama was the predominant genre and does in a certain way conform to contemporary tastes in its strong message of familial responsibility and reconciliation, but is also influenced by European and American crime cinema adding a touch of noir to its clearly delineated worlds of rich and poor which the hero has, perhaps incorrectly, attempted to cross through abandoning his social responsibilities to chase fortune in the wilderness.

First on the scene, however, is lonely sailor Dong-il (Hwang Hae) who has returned to Busan after a six month voyage. He tries to visit his mother who is working in a restaurant, but finds her cold and unreceptive. We learn that prior to becoming a sailor, he’d been unemployed and embarrassed not to be able to support his ageing mother as a son should. Dong-il’s father apparently went off to the mountains to look for gold 20 years ago and hasn’t been heard from since. His mother has remarried and his step-father appears not to like him very much, so Dong-il’s longed for familial reconciliation seems unlikely to take place. Angrily leaving the restaurant, he punches an old hobo in the street in frustration.

Unbeknownst to him, the man, Wun-chil (Kim Seung-ho), is like his father a prospector only apparently a lucky one. After 20 years living “like an animal” in the mountains, he’s struck gold and a lot of it. Wun-chil sells some of the gold to an unscrupulous dealer who immediately cheats him and turns out to be partly responsible for the marriage of the woman he loved to a much wealthier man, and thereafter sets about living as a member of the elite, taking a room at a plush hotel the staff didn’t even want to let him into after taking one look at his mountain man attire. A lengthy flashback informs us that after getting his heart broken, Wun-chil married a woman who was fond of him on the rebound but he never loved her and so the marriage floundered while he became a drunk dependent on his wife’s labour picking coal at the railway. Eventually he decided to leave for the mountains with Dong-il’s dad Dal-su (Heo Jang-gang), leaving his wife and baby daughter Yeong-ok (Yun In-ja) behind. Dal-su passed away shortly after they found the gold together and so Wun-chil is keen to track down Dong-il to ensure he gets his dad’s share of the money while also hoping to reunite with Yeong-ok.

The gold becomes a corrupting influence in Wun-chil’s life. He has been away 20 years and no longer has any friends while those he makes after becoming rich cannot exactly be trusted. The unscrupulous jeweller has him splashed all over the papers where he talks about his desire to find Dong-il and Yeong-ok, causing a series of imposters to appear claiming to be the long lost children as well as one fake detective offering to find them. When Dong-il eventually finds Wun-chil himself, Wun-chil has all but given up and chosen to self isolate to protect himself from the virus of greed and so doesn’t believe Dong-il is who he says he is.

Meanwhile, he’s consumed by a sense of guilt and regret in his abandonment of his family and failure as a man to behave honourably towards the woman that he married. We discover that the motivation for Dal-su and Wun-chil to go into the mountains was less economic than romantic. Dal-su’s wife had apparently left him and he hoped to win her back after getting rich, while Wun-chil was still smarting from the loss of the woman he loved to a wealthier man and thought he could gazump him by happening on a gold mine. On his deathbed, Dal-su is sure his fate is payback for the abandonment of his family, while Wun-chil’s guilt runs still deeper. His wife was eventually killed in a rail accident while he was away, leaving Yeong-ok all alone, eventually taken in as a servant and exploited by a wealthy family. Wun-chil came and got her back, but was unable to care for her, eventually tying her to a tree and walking off which is why he has no idea if she is alive or dead.

Yeong-ok (Um Aing-ran) appears to have survived but has been further corrupted as a member of a vicious street gang, seducing men in the street and then mugging them at knife point but beholden to her boss, Hwang Hog (Park No-sik), who more or less owns her in return for the investment he has made in feeding her. In the course of her activities she encounters Dong-il who heroically fends off her attempt to rob him and prompts her into a reconsideration of her way of life. The youngsters hit it off and begin to fall in love, especially once they discover their shared trauma as children essentially abandoned by irresponsible fathers who ran off to look for gold and never came back.

Of course, their tripartite destinies eventually converge as the gang sets its sites on Wun-chil’s millions while he starts to reflect on the meaninglessness of wealth when you actually have it. He finds himself wandering down to the railway tracks and observing the other women working there in memory of his late wife, slipping a bundle of notes inside the blanket of a baby on its mother’s back and handing more cash to those he passes on his way. That does not mean, however, that he’s willing to surrender his gold which is why he kicks off when he discovers the map to the mine and all his money has been stolen from the hotel. Culminating in a tense shootout between the righteous forces of Dong-il picking up his father’s gun, a regretful Wun-chil hoping to reunite with Yeong-ok, and the gang he hopes to free her from, the battle is not so much over the money but for Wun-chil’s frustrated paternity. Vanquishing the greedy, the family is in a sense restored as Wun-chil vows to become a “good father” to Yeong-ok, embracing Dong-il as a potential son-in-law as the kids support the wounded patriarch back towards civilisation and a presumably happier future.

A Bonanza is available on DVD courtesy of the Korean Film Archive in a set which also includes a bilingual booklet featuring writing by Park Sun-young (Research professor, Center for Korean History at Korea University). It is also available to stream online via the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.