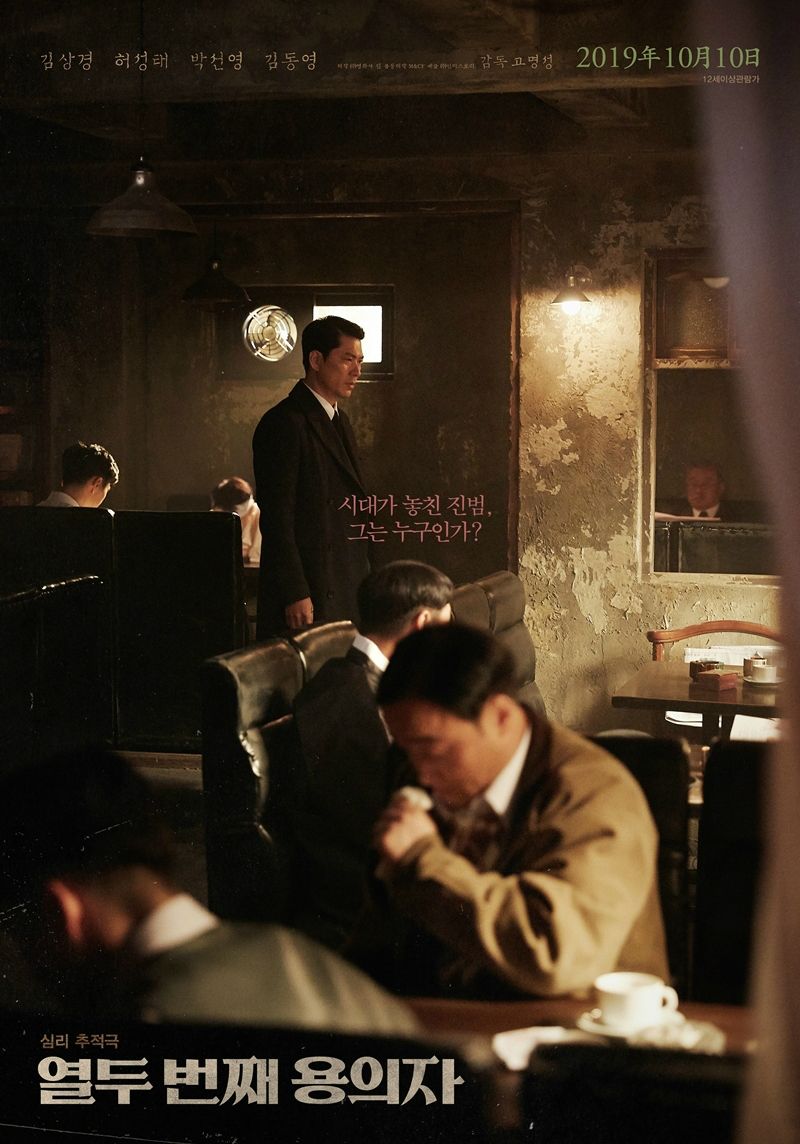

An inspector calls on a small group of artists in the immediate aftermath of the Korean War in Ko Myoung-sung’s taut psychological thriller, The 12th Suspect (열두 번째 용의자, Yeoldu beonjjae Yonguija). Set almost entirely within a tiny tea house, Ko’s steely drama lays bare the contradictions of the new society in slide towards authoritarianism which is itself a product of the failure to deal with the legacy of the colonial past while preoccupied about the “communist” threat in the quite literally divided nation.

The Oriental Teahouse is home to a collection of poets, painters, and Bohemians seeking refuge from the everyday difficulties of life in the post-war city. Their peaceful idyll is rocked by the revelations that one of their number, Doo-hwan, died on a mountain the previous evening most likely murdered. As it turns out, no one seems to have liked Doo-hwan very much. He was “hateful and ignorant” not to mention a bad poet though many are sceptical of the story wondering if he might simply have had an accident. In any case, the newcomer to the cafe turns out to be a policeman, Ki-chae (Kim Sang-kyung), who confirms that Doo-hwan died of a gunshot wound and sets about asking a series of increasingly intense questions about his relations with the cafe’s denizens.

To begin with, Ki-chae seems to be a Columbo-like avuncular detective, polite and sympathetic in his questioning until revealing his true purpose at which he turns into something of a firebreathing demon with a very particular vision of “justice”, hunting down “communist spies” in order to keep the South safe. As the murder weapon appears to be a Soviet-issue pistol, he assumes the killer(s) may be linked to the North accusing one of the patrons of having aided and abetted a cousin who was on the other side while throwing a book on Stalin at a university professor who desperately tries to explain that he’s had it since studying in Russia in his youth when times were different.

Meanwhile, the policeman’s authoritarian sense of justice is gradually exposed as a kind of fascim born of his experiences under Japanese colonial rule. Doo-hwan may have died because of his actions during in the war when he collaborated with Japanese officers agreeing to send young men from his village as conscript soldiers to die for Japan on the frontlines or else as exploited slave labour in the coal mines. Ki-chae is hiding his own dark past while his quest for justice is riddled with corruption masked as patriotism as he vows to wipe out the “communist” threat in order to build a more secure Korea. “The existence of communists is a great misfortune to this country and also a danger” he adds before descending into a violent rage stamping on the face of his interviewee.

His almost hysterical anti-communism is manifested in a general hatred for the kind of people who frequent the Oriental Teahouse, firstly taking them to task for their lifestyles in a time of chaos and privation while later viewing them as cowardly shirkers evading their duty to go to war. “I won’t let you ruin our country” he snarls while simultaneously embarking on an ill thought through argument that the communists are unfairly benefitting from the dire economic situation to “provoke good people”. He justifies his actions in insisting that everything he does is in order to prevent another “horrible war” while continuing to intimidate them into some kind of confession. His questioning reveals the petty jealousies and minor tensions between the artists along with the unreliability of their testimony while eventually exposing their small acts of resistance, cafe owner Suk-hyeon (Heo Sung-tae) determined to stand up to authoritarianism rather than forever be oppressed by it though others it seems are frightened enough by the potential dangers of rebellion to consider turning on their friends and allies. Locked in the tiny cafe with two soldiers blocking the exit, the artists are cornered and terrified as Ki-chae pits one against the other while all around them the prognosis looks bleak in a society in which men like Ki-chae wield ultimate power controlling the future through burying the past.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences.

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences.